If you're like most people, you think that heart disease is a problem for others. But heart disease is the number one killer in the U.S. It is also a major cause of disability. There are many different forms of heart disease. The most common cause of heart disease is narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries, the blood vessels that supply blood to the heart itself. This is called coronary artery disease and happens slowly over time. It's the major reason people have heart attacks.

Other kinds of heart problems may happen to the valves in the heart, or the heart may not pump well and cause heart failure. Some people are born with heart disease.

You can help reduce your risk of heart disease by taking steps to control factors that put you at greater risk:

NIH: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Coronary heart disease—often simply called heart disease—is the main form of heart disease. It is a disorder of the blood vessels of the heart that can lead to heart attack. A heart attack happens when an artery becomes blocked, preventing oxygen and nutrients from getting to the heart. Heart disease is one of several cardiovascular diseases, which are diseases of the heart and blood vessel system. Other cardiovascular diseases include stroke, high blood pressure, angina (chest pain), and rheumatic heart disease.

One reason some women aren't too concerned about heart disease is that they think it can be "cured" with surgery or medication. This is a myth. Heart disease is a lifelong condition—once you get it, you'll always have it. True, procedures such as bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention can help blood and oxygen flow to the heart more easily. But the arteries remain damaged, which means you are more likely to have a heart attack. What's more, the condition of your blood vessels will steadily worsen unless you make changes in your daily habits. Many women die of complications from heart disease, or become permanently disabled. That's why it is so vital to take action to prevent and control this disease. More information is available on cardiovascular diseases on the NHLBI Health Topics Website.

Next: What Are the Risk Factors for Heart Disease?

Risk factors are conditions or habits that make a person more likely to develop a disease. They can also increase the chances that an existing disease will get worse. Important risk factors for heart disease that you can do something about are:

Some risk factors, such as age and family history of early heart disease, can't be changed. For women, age becomes a risk factor at 55. After menopause, women are more apt to get heart disease, in part because their body's production of estrogen drops. Women who have gone through early menopause, either naturally or because they have had a hysterectomy, are twice as likely to develop heart disease as women of the same age who have not yet gone through menopause.

Another reason for the increasing risk is that middle age is a time when women tend to develop risk factors for heart disease. Family history of early heart disease is another risk factor that can't be changed. If your father or brother had a heart attack before age 55, or if your mother or sister had one before age 65, you are more likely to get heart disease yourself. Preeclampsia is another heart disease risk factor that you can't control. However, if you've had the condition, you should take extra care to try and control other heart disease risk factors.

You can make the changes gradually, one at a time. But making them is very important. Other women may wonder: If I have just one risk factor for heart disease—say, I'm overweight or I have high blood cholesterol—aren't I more or less "safe"? Absolutely not. Each risk factor greatly increases a woman's chance of developing heart disease. But having more than one risk factor is especially serious, because risk factors tend to "gang up" and worsen each other's effects. So, the message is clear: Every woman needs to take her heart disease risk seriously—and take action now to reduce that risk.

Next: How do I find out if I am at risk for heart disease?

Last Updated: July 10, 2014

The first step toward heart health is becoming aware of your own personal risk for heart disease. Some risks, such as smoking cigarettes, are obvious: every woman knows whether or not she smokes. But other risk factors, such as high blood pressure or high blood cholesterol, generally don't have obvious signs or symptoms. So you'll need to gather some information to create your personal "heart profile."

You and Your Doctor: A Heart Healthy Partnership

A crucial step in determining your risk is to see your doctor for a thorough checkup. Your doctor can be an important partner in helping you set and reach goals for heart health. But don't wait for your doctor to mention heart disease or its risk factors. Many doctors don't routinely bring up the subject with women patients. Here are some tips for establishing good, clear communication between you and your doctor:

Speak up. Tell your doctor you want to keep your heart healthy and would like help in achieving that goal. Ask questions about your chances of developing heart disease and how you can lower your risk. See "Questions To Ask Your Doctor" on page 15 of The Healthy Heart Handbook for Women ![]() (2.47MB). Also ask for tests that will determine your personal risk factors. (See "Check It Out"

(2.47MB). Also ask for tests that will determine your personal risk factors. (See "Check It Out" ![]() (46KB) on page 16 of The Healthy Heart Handbook for Women.)

(46KB) on page 16 of The Healthy Heart Handbook for Women.)

Keep tabs on treatment. If you already are being treated for heart disease or heart disease risk factors, ask your doctor to review your treatment plan with you. Ask: Is what I'm doing in line with the latest recommendations? Are my treatments working? Are my risk factors under control? If your doctor recommends a medical procedure, ask about its benefits and risks. Find out if you will need to be hospitalized and for how long, and what to expect during the recovery period.

Be open. When your doctor asks you questions, answer as honestly and fully as you can. While certain topics may seem quite personal, discussing them openly can help your doctor find out your chances of developing heart disease. It can also help your doctor work with you to reduce your risk. If you already have heart disease, briefly describe each of your symptoms. Include when each symptom started, how often it happens, and whether it has been getting worse.

Keep it simple. If you don't understand something your doctor says, ask for an explanation in simple language. Be especially sure you understand how to take any medication you are given. If you are worried about understanding what the doctor says, or if you have trouble hearing, bring a friend or relative with you to your appointment. You may want to ask that person to write down the doctor's instructions for you.

Next: What should I know about menopausal hormone therapy and heart disease?

Last Updated: February 29, 2012

Menopausal hormone therapy once seemed the answer for many of the conditions women face as they age. It was thought that hormone therapy could ward off heart disease, osteoporosis, and cancer, while improving women's quality of life. But beginning in July 2002, findings emerged from clinical trials that showed this was not so. In fact, long-term use of hormone therapy poses serious risks and may increase the risk of heart attack and stroke. The findings come from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), launched in 1991 to test ways to prevent a number of medical disorders in postmenopausal women. It consists of a set of clinical studies on hormone therapy, diet modification, and calcium and vitamin D supplements; an observational study; and a community prevention study.

The two hormone therapy clinical studies were both stopped early because of serious risks and the failure to prevent heart disease. Briefly, the estrogen-plus-progestin therapy increased women's risk for heart attacks, stroke, blood clots, and breast cancer. These risks diminished after stopping estrogen-plus-progestin. Estrogen-plus-progestin also doubled the risk of dementia and did not protect women against memory loss. However, the therapy had some benefits: It reduced the risk for colorectal cancer and bone fractures. Estrogen-alone therapy increased the risk for stroke and venous thrombosis (blood clot, usually in one of the deep veins of the legs). It had no effect on heart disease and colorectal cancer, and an uncertain effect on breast cancer. Estrogen alone gave no protection against memory loss, and there were more cases of dementia in those who took the therapy than those on the placebo, although the increase was not statistically significant. Estrogen alone reduced the risk for bone fractures.

While questions remain, the findings make possible some advice about using hormone therapy: Estrogen alone or with progestin should not be used to prevent heart disease. Talk with your doctor about other ways of preventing heart attack and stroke, including lifestyle changes and medicines such as cholesterol-lowering statins and blood pressure drugs.

If You Have Heart Disease: Menopausal hormone therapy was once thought to lower the risk of heart attack and stroke for women with heart disease. But research now shows that women with heart disease should not take it. Menopausal hormone therapy can involve the use of estrogen alone or estrogen plus progestin. For women with heart disease, estrogen alone will not prevent heart attacks, and estrogen plus progestin increases the risk for heart attack during the first few years of use. Estrogen plus progestin also increases the risk for blood clots, stroke, and breast cancer.

Source: National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute, NIH

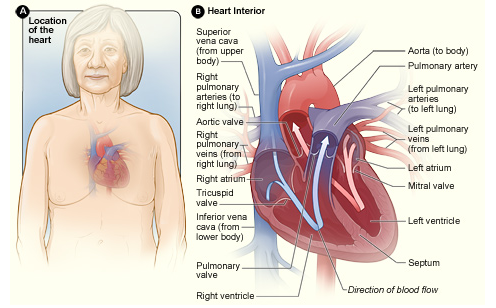

Your heart is a muscular organ that pumps blood to your body. Your heart is at the center of your circulatory system. This system consists of a network of blood vessels, such as arteries, veins, and capillaries. These blood vessels carry blood to and from all areas of your body.

An electrical system controls your heart and uses electrical signals to contract the heart's walls. When the walls contract, blood is pumped into your circulatory system. Inlet and outlet valves in your heart chambers ensure that blood flows in the right direction.

Your heart is vital to your health and nearly everything that goes on in your body. Without the heart's pumping action, blood can't move throughout your body.

Your blood carries the oxygen and nutrients that your organs need to work well. Blood also carries carbon dioxide (a waste product) to your lungs so you can breathe it out.

A healthy heart supplies your body with the right amount of blood at the rate needed to work well. If disease or injury weakens your heart, your body's organs won't receive enough blood to work normally.

Your heart is located under your ribcage in the center of your chest between your right and left lungs. Its muscular walls beat, or contract, pumping blood to all parts of your body.

The size of your heart can vary depending on your age, size, and the condition of your heart. A normal, healthy, adult heart usually is the size of an average clenched adult fist. Some diseases can cause the heart to enlarge.

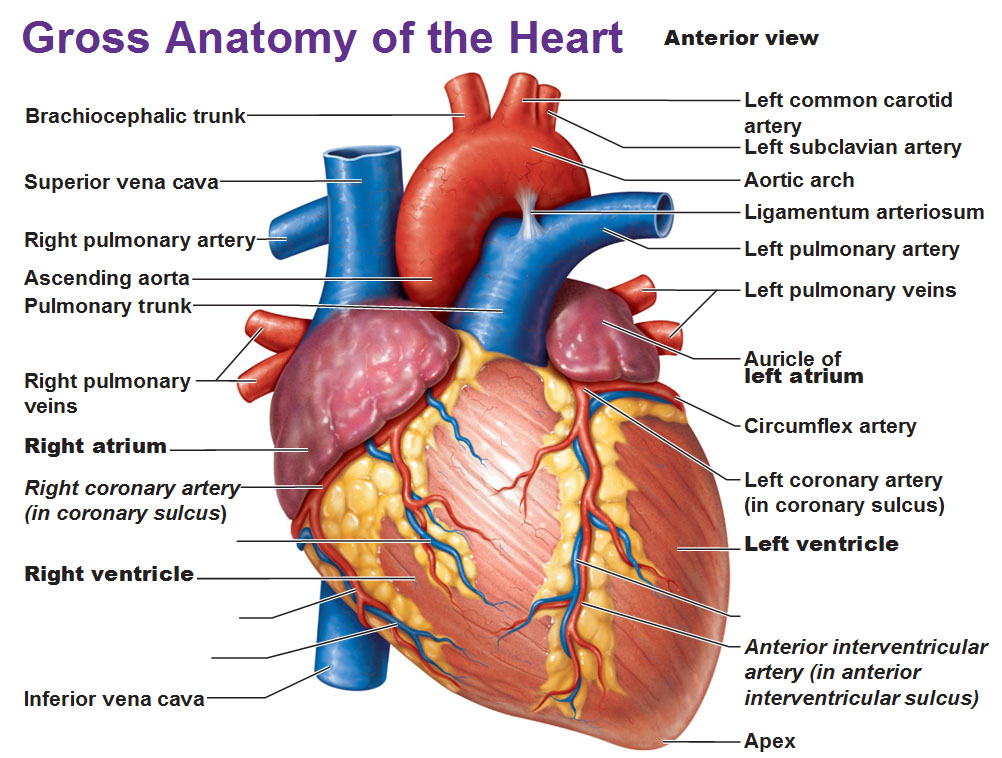

Below is a picture of the outside of a normal, healthy, human heart.

Figure A shows the location of the heart in the body. Figure B shows the front surface of the heart, including the coronary arteries and major blood vessels.

In figure B, the heart is the muscle in the lower half of the picture. The heart has four chambers. The heart's upper chambers, the right and left atria (AY-tree-uh), are shown in purple. The heart's lower chambers, the right and left ventricles (VEN-trih-kuls), are shown in red.

Some of the main blood vessels (arteries and veins) that make up your circulatory system are directly connected to the heart.

In figure B above, the superior and inferior vena cavae are shown in blue to the left of the heart muscle as you look at the picture. These veins are the largest veins in your body.

After your body's organs and tissues have used the oxygen in your blood, the vena cavae carry the oxygen-poor blood back to the right atrium of your heart.

The superior vena cava carries oxygen-poor blood from the upper parts of your body, including your head, chest, arms, and neck. The inferior vena cava carries oxygen-poor blood from the lower parts of your body.

The oxygen-poor blood from the vena cavae flows into your heart's right atrium and then to the right ventricle. From the right ventricle, the blood is pumped through the pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary) arteries (shown in blue in the center of figure B) to your lungs.

Once in the lungs, the blood travels through many small, thin blood vessels called capillaries. There, the blood picks up more oxygen and transfers carbon dioxide to the lungs—a process called gas exchange. To learn more about gas exchange, go to the Health Topics How the Lungs Work article.

The oxygen-rich blood passes from your lungs back to your heart through the pulmonary veins (shown in red to the left of the right atrium in figure B).

Oxygen-rich blood from your lungs passes through the pulmonary veins (shown in red to the right of the left atrium in figure B above). The blood enters the left atrium and is pumped into the left ventricle.

From the left ventricle, the oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the rest of your body through the aorta. The aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood to your body.

Like all of your organs, your heart needs oxygen-rich blood. As blood is pumped out of your heart's left ventricle, some of it flows into the coronary arteries (shown in red in figure B).

Your coronary arteries are located on your heart's surface at the beginning of the aorta. They carry oxygen-rich blood to all parts of your heart.

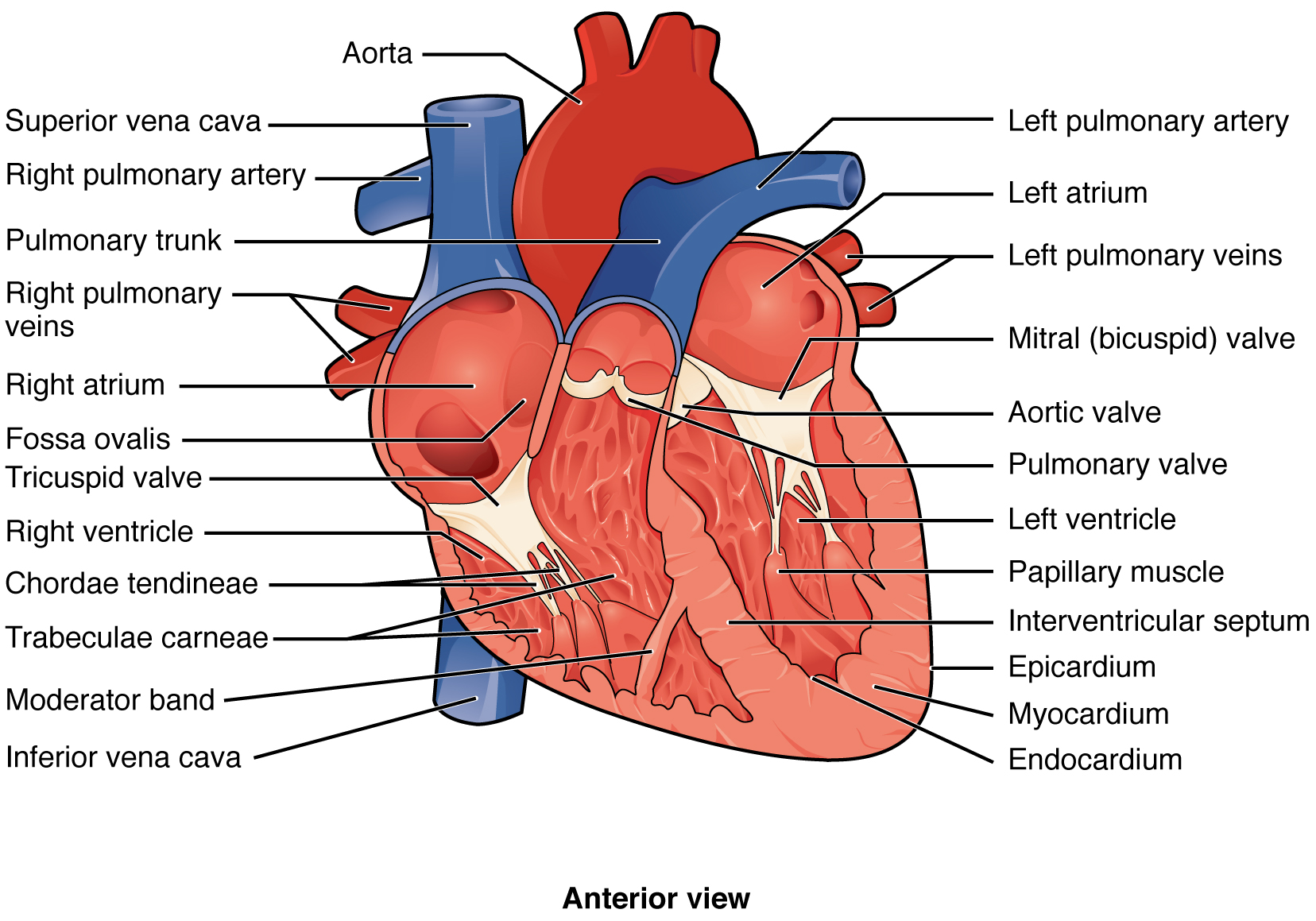

Below is a picture of the inside of a normal, healthy, human heart.

Figure A shows the location of the heart in the body. Figure B shows a cross-section of a healthy heart and its inside structures. The blue arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-poor blood flows through the heart to the lungs. The red arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs into the heart and then out to the body.

Figure B shows the inside of your heart and how it's divided into four chambers. The two upper chambers of your heart are called the atria. They receive and collect blood.

The two lower chambers of your heart are called ventricles. The ventricles pump blood out of your heart to other parts of your body.

An internal wall of tissue divides the right and left sides of your heart. This wall is called the septum.

The area of the septum that divides the atria is called the atrial or interatrial septum. The area of the septum that divides the ventricles is called the ventricular or interventricular septum.

Figure B shows your heart's four valves. Shown counterclockwise in the picture, the valves include the aortic (ay-OR-tik) valve, the tricuspid (tri-CUSS-pid) valve, the pulmonary valve, and the mitral (MI-trul) valve.

The arrows in figure B show the direction that blood flows through your heart. The light blue arrow shows that blood enters the right atrium of your heart from the superior and inferior vena cavae.

From the right atrium, blood is pumped into the right ventricle. From the right ventricle, blood is pumped to your lungs through the pulmonary arteries.

The light red arrow shows oxygen-rich blood coming from your lungs through the pulmonary veins into your heart's left atrium. From the left atrium, the blood is pumped into the left ventricle. The left ventricle pumps the blood to the rest of your body through the aorta.

For the heart to work well, your blood must flow in only one direction. Your heart's valves make this possible. Both of your heart's ventricles have an "in" (inlet) valve from the atria and an "out" (outlet) valve leading to your arteries.

Healthy valves open and close in exact coordination with the pumping action of your heart's atria and ventricles. Each valve has a set of flaps called leaflets or cusps that seal or open the valve. This allows blood to pass through the chambers and into your arteries without backing up or flowing backward.

The animation below shows how your heart pumps blood. Click the "start" button to play the animation. Written and spoken explanations are provided with each frame. Use the buttons in the lower right corner to pause, restart, or replay the animation, or use the scroll bar below the buttons to move through the frames.

The animation shows how blood flows through the heart as it contracts and relaxes.

Almost everyone has heard the real or recorded sound of a heartbeat. When your heart beats, it makes a "lub-DUB" sound. Between the time you hear "lub" and "DUB," blood is pumped through your heart and circulatory system.

A heartbeat may seem like a simple, repeated event. However, it's a complex series of very precise and coordinated events. These events take place inside and around your heart.

Each side of your heart uses an inlet valve to help move blood between the atrium and ventricle. The tricuspid valve does this between the right atrium and ventricle. The mitral valve does this between the left atrium and ventricle. The "lub" is the sound of the tricuspid and mitral valves closing.

Each of your heart's ventricles also has an outlet valve. The right ventricle uses the pulmonary valve to help move blood into the pulmonary arteries. The left ventricle uses the aortic valve to do the same for the aorta. The "DUB" is the sound of the aortic and pulmonary valves closing.

Each heartbeat has two basic parts: diastole (di-AS-toe-lee) and systole (SIS-toe-lee).

During diastole, the atria and ventricles of your heart relax and begin to fill with blood. At the end of diastole, your heart's atria contract (atrial systole) and pump blood into the ventricles.

The atria then begin to relax. Next, your heart's ventricles contract (ventricular systole) and pump blood out of your heart.

Your heart uses its four valves to ensure your blood flows in only one direction. Healthy valves open and close in coordination with the pumping action of your heart's atria and ventricles.

Each valve has a set of flaps called leaflets or cusps that seal or open the valve. The cusps allow pumped blood to pass through the chambers and into your blood vessels without backing up or flowing backward.

Oxygen-poor blood from the vena cavae fills your heart's right atrium. The atrium contracts (atrial systole). The tricuspid valve located between the right atrium and ventricle opens for a short time and then shuts. This allows blood to enter the right ventricle without flowing back into the right atrium.

When your heart's right ventricle fills with blood, it contracts (ventricular systole). The pulmonary valve located between your right ventricle and pulmonary artery opens and closes quickly.

This allows blood to enter into your pulmonary arteries without flowing back into the right ventricle. This is important because the right ventricle begins to refill with more blood through the tricuspid valve. Blood travels through the pulmonary arteries to your lungs to pick up oxygen.

Oxygen-rich blood returns from the lungs to your heart's left atrium through the pulmonary veins. As your heart's left atrium fills with blood, it contracts. This event is called atrial systole.

The mitral valve located between the left atrium and left ventricle opens and closes quickly. This allows blood to pass from the left atrium into the left ventricle without flowing backward.

As the left ventricle fills with blood, it contracts. This event is called ventricular systole. The aortic valve located between the left ventricle and aorta opens and closes quickly. This allows blood to flow into the aorta. The aorta is the main artery that carries blood from your heart to the rest of your body.

The aortic valve closes quickly to prevent blood from flowing back into the left ventricle, which already is filling up with new blood.

When your heart pumps blood through your arteries, it creates a pulse that you can feel on the arteries close to the skin's surface. For example, you can feel the pulse on the artery inside of your wrist, below your thumb.

You can count how many times your heart beats by taking your pulse. You will need a watch with a second hand.

To find your pulse, gently place your index and middle fingers on the artery located on the inner wrist of either arm, below your thumb. You should feel a pulsing or tapping against your fingers.

Watch the second hand and count the number of pulses you feel in 30 seconds. Double that number to find out your heart rate or pulse for 1 minute.

The usual resting pulse for an adult is 60 to 100 beats per minute. To find your resting pulse, count your pulse after you have been sitting or resting quietly for at least 10 minutes.

Your heart and blood vessels make up your overall blood circulatory system. Your blood circulatory system is made up of four subsystems.

Arterial circulation is the part of your circulatory system that involves arteries, like the aorta and pulmonary arteries. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from your heart. (The exception is the coronary arteries, which supply your heart muscle with oxygen-rich blood.)

Healthy arteries are strong and elastic (stretchy). They become narrow between heartbeats, and they help keep your blood pressure consistent. This helps blood move through your body.

Arteries branch into smaller blood vessels called arterioles (ar-TEER-e-ols). Arteries and arterioles have strong, flexible walls that allow them to adjust the amount and rate of blood flowing to parts of your body.

Venous circulation is the part of your circulatory system that involves veins, like the vena cavae and pulmonary veins. Veins are blood vessels that carry blood to your heart.

Veins have thinner walls than arteries. Veins can widen as the amount of blood passing through them increases.

Capillary circulation is the part of your circulatory system where oxygen, nutrients, and waste pass between your blood and parts of your body.

Capillaries are very small blood vessels. They connect the arterial and venous circulatory subsystems.

The importance of capillaries lies in their very thin walls. Oxygen and nutrients in your blood can pass through the walls of the capillaries to the parts of your body that need them to work normally.

Capillaries' thin walls also allow waste products like carbon dioxide to pass from your body's organs and tissues into the blood, where it's taken away to your lungs.

Pulmonary circulation is the movement of blood from the heart to the lungs and back to the heart again. Pulmonary circulation includes both arterial and venous circulation.

Oxygen-poor blood is pumped to the lungs from the heart (arterial circulation). Oxygen-rich blood moves from the lungs to the heart through the pulmonary veins (venous circulation).

Pulmonary circulation also includes capillary circulation. Oxygen you breathe in from the air passes through your lungs into your blood through the many capillaries in the lungs. Oxygen-rich blood moves through your pulmonary veins to the left side of your heart and out of the aorta to the rest of your body.

Capillaries in the lungs also remove carbon dioxide from your blood so that your lungs can breathe the carbon dioxide out into the air.

he animation below shows how your heart's electrical system works. Click the "start" button to play the animation. Written and spoken explanations are provided with each frame. Use the buttons in the lower right corner to pause, restart, or replay the animation, or use the scroll bar below the buttons to move through the frames.

The animation shows how the heart's internal electrical system causes the heart to pump blood.

Your heart's electrical system controls all the events that occur when your heart pumps blood. The electrical system also is called the cardiac conduction system. If you've ever seen the heart test called an EKG (electrocardiogram), you've seen a graphical picture of the heart's electrical activity.

Your heart's electrical system is made up of three main parts:

A heartbeat is a complex series of events. These events take place inside and around your heart. A heartbeat is a single cycle in which your heart's chambers relax and contract to pump blood. This cycle includes the opening and closing of the inlet and outlet valves of the right and left ventricles of your heart.

Each heartbeat has two basic parts: diastole and systole. During diastole, the atria and ventricles of your heart relax and begin to fill with blood.

At the end of diastole, your heart's atria contract (atrial systole) and pump blood into the ventricles. The atria then begin to relax. Your heart's ventricles then contract (ventricular systole), pumping blood out of your heart.

Each beat of your heart is set in motion by an electrical signal from within your heart muscle. In a normal, healthy heart, each beat begins with a signal from the SA node. This is why the SA node sometimes is called your heart's natural pacemaker. Your pulse, or heart rate, is the number of signals the SA node produces per minute.

The signal is generated as the vena cavae fill your heart's right atrium with blood from other parts of your body. The signal spreads across the cells of your heart's right and left atria.

This signal causes the atria to contract. This action pushes blood through the open valves from the atria into both ventricles.

The signal arrives at the AV node near the ventricles. It slows for an instant to allow your heart's right and left ventricles to fill with blood. The signal is released and moves along a pathway called the bundle of His, which is located in the walls of your heart's ventricles.

From the bundle of His, the signal fibers divide into left and right bundle branches through the Purkinje fibers. These fibers connect directly to the cells in the walls of your heart's left and right ventricles (see yellow on the picture in the animation).

The signal spreads across the cells of your ventricle walls, and both ventricles contract. However, this doesn't happen at exactly the same moment.

The left ventricle contracts an instant before the right ventricle. This pushes blood through the pulmonary valve (for the right ventricle) to your lungs, and through the aortic valve (for the left ventricle) to the rest of your body.

As the signal passes, the walls of the ventricles relax and await the next signal.

This process continues over and over as the atria refill with blood and more electrical signals come from the SA node.

Your heart is made up of many parts working together to pump blood. In a healthy heart, all the parts work well so that your heart pumps blood normally. As a result, all parts of your body that depend on the heart to deliver blood also stay healthy.

Heart disease can disrupt a heart's normal electrical system and pumping functions. Diseases and conditions of the heart's muscle make it hard for your heart to properly pump blood.

Damaged or diseased blood vessels make the heart work harder than normal. Problems with the heart's electrical system, called arrhythmias (ah-RITH-me-ahs), can make it hard for the heart to pump blood efficiently.

Health Topics has many articles about heart diseases and conditions. For more information, go to the Health Topics home page.

Source: National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute, NIH

What Is Coronary Heart Disease?

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a disease in which a waxy substance called plaque (plak) builds up inside the coronary arteries. These arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to your heart muscle.

When plaque builds up in the arteries, the condition is called atherosclerosis (ATH-er-o-skler-O-sis). The buildup of plaque occurs over many years.

Over time, plaque can harden or rupture (break open). Hardened plaque narrows the coronary arteries and reduces the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

If the plaque ruptures, a blood clot can form on its surface. A large blood clot can mostly or completely block blood flow through a coronary artery. Over time, ruptured plaque also hardens and narrows the coronary arteries.

If the flow of oxygen-rich blood to your heart muscle is reduced or blocked, angina (an-JI-nuh or AN-juh-nuh) or a heart attack can occur.

Angina is chest pain or discomfort. It may feel like pressure or squeezing in your chest. The pain also can occur in your shoulders, arms, neck, jaw, or back. Angina pain may even feel like indigestion.

A heart attack occurs if the flow of oxygen-rich blood to a section of heart muscle is cut off. If blood flow isn’t restored quickly, the section of heart muscle begins to die. Without quick treatment, a heart attack can lead to serious health problems or death.

Over time, CHD can weaken the heart muscle and lead to heart failure and arrhythmias (ah-RITH-me-ahs). Heart failure is a condition in which your heart can't pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs. Arrhythmias are problems with the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat.

CHD is the most common type of heart disease. In the United States, CHD is the #1 cause of death for both men and women. Lifestyle changes, medicines, and medical procedures can help prevent or treat CHD. These treatments may reduce the risk of related health problems.

Research suggests that coronary heart disease (CHD) starts when certain factors damage the inner layers of the coronary arteries. These factors include:

Plaque might begin to build up where the arteries are damaged. The buildup of plaque in the coronary arteries may start in childhood.

Over time, plaque can harden or rupture (break open). Hardened plaque narrows the coronary arteries and reduces the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the heart. This can cause angina (chest pain or discomfort).

If the plaque ruptures, blood cell fragments called platelets (PLATE-lets) stick to the site of the injury. They may clump together to form blood clots.

Blood clots can further narrow the coronary arteries and worsen angina. If a clot becomes large enough, it can mostly or completely block a coronary artery and cause a heart attack.

In the United States, coronary heart disease (CHD) is a leading cause of death for both men and women. Each year, about 375,000 Americans die from CHD.

Certain traits, conditions, or habits may raise your risk for CHD. The more risk factors you have, the more likely you are to develop the disease.

You can control many risk factors, which may help prevent or delay CHD.

Although older age and a family history of early heart disease are risk factors, it doesn't mean that you’ll develop CHD if you have one or both. Controlling other risk factors often can lessen genetic influences and help prevent CHD, even in older adults.

Researchers continue to study other possible risk factors for CHD.

High levels of a protein called C-reactive protein (CRP) in the blood may raise the risk of CHD and heart attack. High levels of CRP are a sign of inflammation in the body.

Inflammation is the body's response to injury or infection. Damage to the arteries' inner walls may trigger inflammation and help plaque grow.

Research is under way to find out whether reducing inflammation and lowering CRP levels also can reduce the risk of CHD and heart attack.

High levels of triglycerides (tri-GLIH-seh-rides) in the blood also may raise the risk of CHD, especially in women. Triglycerides are a type of fat.

Other conditions and factors also may contribute to CHD, including:

For more detailed information, go to the Health Topics Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors article.

A common symptom of coronary heart disease (CHD) is angina. Angina is chest pain or discomfort that occurs if an area of your heart muscle doesn't get enough oxygen-rich blood.

Angina may feel like pressure or squeezing in your chest. You also may feel it in your shoulders, arms, neck, jaw, or back. Angina pain may even feel like indigestion. The pain tends to get worse with activity and go away with rest. Emotional stress also can trigger the pain.

Another common symptom of CHD is shortness of breath. This symptom occurs if CHD causes heart failure. When you have heart failure, your heart can't pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs. Fluid builds up in your lungs, making it hard to breathe.

The severity of these symptoms varies. They may get more severe as the buildup of plaque continues to narrow the coronary arteries.

Some people who have CHD have no signs or symptoms—a condition called silent CHD. The disease might not be diagnosed until a person has signs or symptoms of a heart attack, heart failure, or an arrhythmia (an irregular heartbeat).

A heart attack occurs if the flow of oxygen-rich blood to a section of heart muscle is cut off. This can happen if an area of plaque in a coronary artery ruptures (breaks open).

Blood cell fragments called platelets stick to the site of the injury and may clump together to form blood clots. If a clot becomes large enough, it can mostly or completely block blood flow through a coronary artery.

If the blockage isn’t treated quickly, the portion of heart muscle fed by the artery begins to die. Healthy heart tissue is replaced with scar tissue. This heart damage may not be obvious, or it may cause severe or long-lasting problems.

Figure A shows the location of the heart in the body. Figure B is an overview of a heart and coronary artery showing damage (dead heart muscle) caused by a heart attack. Figure C is a cross-section of the coronary artery with plaque buildup and a blood clot.

The most common heart attack symptom is chest pain or discomfort. Most heart attacks involve discomfort in the center or left side of the chest that often lasts for more than a few minutes or goes away and comes back.

The discomfort can feel like uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness, or pain. The feeling can be mild or severe. Heart attack pain sometimes feels like indigestion or heartburn.

The symptoms of angina can be similar to the symptoms of a heart attack. Angina pain usually lasts for only a few minutes and goes away with rest.

Chest pain or discomfort that doesn’t go away or changes from its usual pattern (for example, occurs more often or while you’re resting) might be a sign of a heart attack. If you don’t know whether your chest pain is angina or a heart attack, call 9–1–1.

All chest pain should be checked by a doctor.

Other common signs and symptoms of a heart attack include:

For more information, go to the Health Topics Heart Attack article.

Heart failure is a condition in which your heart can't pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs. Heart failure doesn't mean that your heart has stopped or is about to stop working.

The most common signs and symptoms of heart failure are shortness of breath or trouble breathing; fatigue; and swelling in the ankles, feet, legs, stomach, and veins in the neck.

All of these symptoms are the result of fluid buildup in your body. When symptoms start, you may feel tired and short of breath after routine physical effort, like climbing stairs.

For more information, go to the Health Topics Heart Failure article.

An arrhythmia is a problem with the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat. When you have an arrhythmia, you may notice that your heart is skipping beats or beating too fast.

Some people describe arrhythmias as a fluttering feeling in the chest. These feelings are called palpitations (pal-pih-TA-shuns).

Some arrhythmias can cause your heart to suddenly stop beating. This condition is called sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). SCA usually causes death if it's not treated within minutes.

For more information, go to the Health Topics Arrhythmia article.

Your doctor will diagnose coronary heart disease (CHD) based on your medical and family histories, your risk factors for CHD, a physical exam, and the results from tests and procedures.

No single test can diagnose CHD. If your doctor thinks you have CHD, he or she may recommend one or more of the following tests.

An EKG is a simple, painless test that detects and records the heart's electrical activity. The test shows how fast the heart is beating and its rhythm (steady or irregular). An EKG also records the strength and timing of electrical signals as they pass through the heart.

An EKG can show signs of heart damage due to CHD and signs of a previous or current heart attack.

During stress testing, you exercise to make your heart work hard and beat fast while heart tests are done. If you can't exercise, you may be given medicine to raise your heart rate.

When your heart is working hard and beating fast, it needs more blood and oxygen. Plaque-narrowed arteries can't supply enough oxygen-rich blood to meet your heart's needs.

A stress test can show possible signs and symptoms of CHD, such as:

If you can't exercise for as long as what is considered normal for someone your age, your heart may not be getting enough oxygen-rich blood. However, other factors also can prevent you from exercising long enough (for example, lung diseases, anemia, or poor general fitness).

As part of some stress tests, pictures are taken of your heart while you exercise and while you rest. These imaging stress tests can show how well blood is flowing in your heart and how well your heart pumps blood when it beats.

Echocardiography (echo) uses sound waves to create a moving picture of your heart. The picture shows the size and shape of your heart and how well your heart chambers and valves are working.

Echo also can show areas of poor blood flow to the heart, areas of heart muscle that aren't contracting normally, and previous injury to the heart muscle caused by poor blood flow.

A chest x ray takes pictures of the organs and structures inside your chest, such as your heart, lungs, and blood vessels.

A chest x ray can reveal signs of heart failure, as well as lung disorders and other causes of symptoms not related to CHD.

Blood tests check the levels of certain fats, cholesterol, sugar, and proteins in your blood. Abnormal levels might be a sign that you're at risk for CHD.

Your doctor may recommend coronary angiography (an-jee-OG-rah-fee) if other tests or factors show that you're likely to have CHD. This test uses dye and special x rays to show the insides of your coronary arteries.

To get the dye into your coronary arteries, your doctor will use a procedure called cardiac catheterization (KATH-eh-ter-ih-ZA-shun).

A thin, flexible tube called a catheter is put into a blood vessel in your arm, groin (upper thigh), or neck. The tube is threaded into your coronary arteries, and the dye is released into your bloodstream.

Special x rays are taken while the dye is flowing through your coronary arteries. The dye lets your doctor study the flow of blood through your heart and blood vessels.

Cardiac catheterization usually is done in a hospital. You're awake during the procedure. It usually causes little or no pain, although you may feel some soreness in the blood vessel where your doctor inserts the catheter.

Treatments for coronary heart disease (CHD) include lifestyle changes, medicines, and medical procedures. Treatment goals may include:

Making lifestyle changes often can help prevent or treat CHD. Lifestyle changes might be the only treatment that some people need.

A healthy diet is an important part of a healthy lifestyle. Following a healthy diet can prevent or reduce high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol and help you maintain a healthy weight.

For information about healthy eating, go to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI's) Aim for a Healthy Weight Web site. This site provides practical tips on healthy eating, physical activity, and controlling your weight.

Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC). Your doctor may recommend TLC if you have high blood cholesterol. TLC is a three-part program that includes a healthy diet, physical activity, and weight management.

With the TLC diet, less than 7 percent of your daily calories should come from saturated fat. This kind of fat is found in some meats, dairy products, chocolate, baked goods, and deep-fried and processed foods.

No more than 25 to 35 percent of your daily calories should come from all fats, including saturated, trans, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats.

You also should have less than 200 mg a day of cholesterol. The amounts of cholesterol and the types of fat in prepared foods can be found on the foods' Nutrition Facts labels.

Foods high in soluble fiber also are part of a healthy diet. They help prevent the digestive tract from absorbing cholesterol. These foods include:

A diet rich in fruits and vegetables can increase important cholesterol-lowering compounds in your diet. These compounds, called plant stanols or sterols, work like soluble fiber.

A healthy diet also includes some types of fish, such as salmon, tuna (canned or fresh), and mackerel. These fish are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids. These acids may help protect the heart from blood clots and inflammation and reduce the risk of heart attack. Try to have about two fish meals every week.

You also should try to limit the amount of sodium (salt) that you eat. This means choosing low-salt and "no added salt" foods and seasonings at the table or while cooking. The Nutrition Facts label on food packaging shows the amount of sodium in the item.

Try to limit drinks that contain alcohol. Too much alcohol will raise your blood pressure and triglyceride level. (Triglycerides are a type of fat found in the blood.) Alcohol also adds extra calories, which will cause weight gain.

Men should have no more than two drinks containing alcohol a day. Women should have no more than one drink containing alcohol a day. One drink is a glass of wine, beer, or a small amount of hard liquor.

For more information about TLC, go to the NHLBI's "Your Guide to Lowering Your Cholesterol With TLC."

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH). Your doctor may recommend the DASH eating plan if you have high blood pressure. The DASH eating plan focuses on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other foods that are heart healthy and low in fat, cholesterol, and sodium.

DASH also focuses on fat-free or low-fat milk and dairy products, fish, poultry, and nuts. The DASH eating plan is reduced in red meats (including lean red meats), sweets, added sugars, and sugar-containing beverages. It's rich in nutrients, protein, and fiber.

The DASH eating plan is a good healthy eating plan, even for those who don’t have high blood pressure. For more information, go to the NHLBI’s "Your Guide to Lowering Your Blood Pressure With DASH."

Routine physical activity can lower many CHD risk factors, including LDL ("bad") cholesterol, high blood pressure, and excess weight.

Physical activity also can lower your risk for diabetes and raise your HDL cholesterol level. HDL is the "good" cholesterol that helps prevent CHD.

Talk with your doctor before you start a new exercise plan. Ask him or her how much and what kinds of physical activity are safe for you.

People gain health benefits from as little as 60 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week. The more active you are, the more you will benefit.

For more information about physical activity, go to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' "2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans," the Health Topics Physical Activity and Your Heart article, and the NHLBI's "Your Guide to Physical Activity and Your Heart."

Maintaining a healthy weight can lower your risk for CHD. A general goal to aim for is a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25.

BMI measures your weight in relation to your height and gives an estimate of your total body fat. You can use the NHLBI's online BMI calculator to figure out your BMI, or your doctor can help you.

A BMI between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight. A BMI of 30 or more is considered obese. A BMI of less than 25 is the goal for preventing and treating CHD. Your doctor or other health care provider can help you set an appropriate BMI goal.

For more information about losing weight or maintaining a healthy weight, go to the Health Topics Overweight and Obesity article.

If you smoke, quit. Smoking can raise your risk for CHD and heart attack and worsen other CHD risk factors. Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit smoking. Also, try to avoid secondhand smoke.

If you have trouble quitting smoking on your own, consider joining a support group. Many hospitals, workplaces, and community groups offer classes to help people quit smoking.

For more information about how to quit smoking, go to the Health Topics Smoking and Your Heart article and the NHLBI's "Your Guide to a Healthy Heart."

Research shows that the most commonly reported "trigger" for a heart attack is an emotionally upsetting event—particularly one involving anger. Also, some of the ways people cope with stress—such as drinking, smoking, or overeating—aren't healthy.

Learning how to manage stress, relax, and cope with problems can improve your emotional and physical health. Having supportive people in your life with whom you can share your feelings or concerns can help relieve stress.

Physical activity, medicine, and relaxation therapy also can help relieve stress. You may want to consider taking part in a stress management program.

You may need medicines to treat CHD if lifestyle changes aren't enough. Medicines can:

Medicines used to treat CHD include anticoagulants (AN-te-ko-AG-u-lants), also called blood thinners; aspirin and other anticlotting medicines; ACE inhibitors; beta blockers; calcium channel blockers; nitroglycerin; glycoprotein IIb-IIIa; statins; and fish oil and other supplements high in omega-3 fatty acids.

You may need a procedure or surgery to treat CHD. Both angioplasty and CABG are used to treat blocked coronary arteries. You and your doctor can discuss which treatment is right for you.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), commonly known as angioplasty, is a nonsurgical procedure that opens blocked or narrowed coronary arteries.

A thin, flexible tube with a balloon or other device on the end is threaded through a blood vessel to the narrowed or blocked coronary artery.

Once in place, the balloon is inflated to compress the plaque against the wall of the artery. This restores blood flow through the artery.

During the procedure, the doctor may put a small mesh tube called a stent in the artery. The stent helps prevent blockages in the artery in the months or years after angioplasty.

For more information, go to the Health Topics PCI article.

CABG is a type of surgery. In CABG, arteries or veins from other areas in your body are used to bypass (that is, go around) your narrowed coronary arteries. CABG can improve blood flow to your heart, relieve chest pain, and possibly prevent a heart attack.

For more information, go to the Health Topics Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting article.

Your doctor may prescribe cardiac rehabilitation (rehab) for angina or after CABG, angioplasty, or a heart attack. Almost everyone who has CHD can benefit from cardiac rehab.

Cardiac rehab is a medically supervised program that may help improve the health and well-being of people who have heart problems.

The cardiac rehab team may include doctors, nurses, exercise specialists, physical and occupational therapists, dietitians or nutritionists, and psychologists or other mental health specialists.

Rehab has two parts:

For more information, go to the Health Topics Cardiac Rehabilitation article.

Taking action to control your risk factors can help prevent or delay coronary heart disease (CHD). Your risk for CHD increases with the number of risk factors you have.

One step you can take is to adopt a healthy lifestyle. Following a healthy diet is an important part of a healthy lifestyle.

A healthy diet includes a variety of vegetables and fruits. It also includes whole grains, fat-free or low-fat dairy products, and protein foods, such as lean meats, poultry without skin, seafood, processed soy products, nuts, seeds, and beans and peas.

A healthy diet is low in sodium (salt), added sugars, solid fats, and refined grains. Solid fats are saturated fat and trans fatty acids. Refined grains come from processing whole grains, which results in a loss of nutrients (such as dietary fiber).

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI's) Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) are two programs that promote healthy eating.

If you're overweight or obese, work with your doctor to create a reasonable weight-loss plan. Controlling your weight helps you control CHD risk factors.

Be as physically active as you can. Physical activity can improve your fitness level and your health. Talk with your doctor about what types of activity are safe for you.

For more information about physical activity, go to the Health Topics Physical Activity and Your Heart article and the NHLBI’s “Your Guide to Physical Activity and Your Heart.”

If you smoke, quit. Smoking can damage and tighten blood vessels and raise your risk for CHD. Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit. Also, try to avoid secondhand smoke.

For more information about quitting smoking, go to the Health Topics Smoking and Your Heart article and the NHLBI’s “Your Guide to a Healthy Heart.”

Know your family history of health problems related to CHD. If you or someone in your family has CHD, be sure to tell your doctor.

If lifestyle changes aren't enough, you also may need medicines to control your CHD risk factors. Take all of your medicines as prescribed.

For more information about lifestyle changes and medicines, go to "How Is Coronary Heart Disease Treated?"

Coronary heart disease (CHD) can cause serious complications. However, if you follow your doctor's advice and adopt healthy lifestyle habits, you can prevent or reduce the risk of:

Lifestyle changes and medicines can help control CHD. Lifestyle changes include following a healthy diet, being physically active, maintaining a healthy weight, quitting smoking, and managing stress.

For more information about lifestyle changes and medicines, go to "How Is Coronary Heart Disease Treated?"

Work closely with your doctor to control your blood pressure and manage your blood cholesterol and blood sugar levels.

A blood test called a lipoprotein panel will measure your cholesterol and triglyceride levels. A fasting blood glucose test will check your blood sugar level and show whether you're at risk for or have diabetes.

These tests show whether your risk factors are controlled, or whether your doctor needs to adjust your treatment for better results.

Talk with your doctor about how often you should schedule office visits or blood tests. Between those visits, call your doctor if you have any new symptoms or if your symptoms worsen.

CHD raises your risk for a heart attack. Learn the signs and symptoms of a heart attack, and call 9–1–1 if you have any of these symptoms:

Symptoms also may include sleep problems, fatigue (tiredness), and lack of energy.

The symptoms of angina can be similar to the symptoms of a heart attack. Angina pain usually lasts for only a few minutes and goes away with rest.

Chest pain or discomfort that doesn’t go away or changes from its usual pattern (for example, occurs more often or while you’re resting) can be a sign of a heart attack. If you don’t know whether your chest pain is angina or a heart attack, call 9–1–1.

Let the people you see regularly know you're at risk for a heart attack. They can seek emergency care for you if you suddenly faint, collapse, or have other severe symptoms.

Living with CHD may cause fear, anxiety, depression, and stress. You may worry about heart problems or making lifestyle changes that are necessary for your health.

Talk about how you feel with your health care team. Talking to a professional counselor also can help. If you’re very depressed, your doctor may recommend medicines or other treatments that can improve your quality of life.

Joining a patient support group may help you adjust to living with CHD. You can see how other people who have the same symptoms have coped with them. Talk with your doctor about local support groups or check with an area medical center.

Support from family and friends also can help relieve stress and anxiety. Let your loved ones know how you feel and what they can do to help you.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is strongly committed to supporting research aimed at preventing and treating heart, lung, and blood diseases and conditions and sleep disorders.

NHLBI-supported research has led to many advances in medical knowledge and care. For example, this research has helped doctors learn more about coronary heart disease (CHD), its risk factors, and ways to prevent and treat the disease.

The NHLBI continues to support research aimed at learning more about CHD. For example, NHLBI-supported research includes studies that:

Much of this research depends on the willingness of volunteers to take part in clinical trials. Clinical trials test new ways to prevent, diagnose, or treat various diseases and conditions.

For example, new treatments for a disease or condition (such as medicines, medical devices, surgeries, or procedures) are tested in volunteers who have the illness. Testing shows whether a treatment is safe and effective in humans before it is made available for widespread use.

By taking part in a clinical trial, you can gain access to new treatments before they’re widely available. You also will have the support of a team of health care providers, who will likely monitor your health closely. Even if you don’t directly benefit from the results of a clinical trial, the information gathered can help others and add to scientific knowledge.

If you volunteer for a clinical trial, the research will be explained to you in detail. You’ll learn about treatments and tests you may receive, and the benefits and risks they may pose. You’ll also be given a chance to ask questions about the research. This process is called informed consent.

If you agree to take part in the trial, you’ll be asked to sign an informed consent form. This form is not a contract. You have the right to withdraw from a study at any time, for any reason. Also, you have the right to learn about new risks or findings that emerge during the trial.

For more information about clinical trials related to CHD, talk with your doctor. You also can visit the following Web sites to learn more about clinical research and to search for clinical trials:

For more information about clinical trials for children, visit the NHLBI’s Children and Clinical Studies Web page.

Source: National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute, NIH

Risk Factors: What Are Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors?

Coronary heart disease risk factors are conditions or habits that raise your risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and heart attack. These risk factors also increase the chance that existing CHD will worsen.

CHD, also called coronary artery disease, is a condition in which a waxy substance called plaque (plak) builds up on the inner walls of the coronary arteries. These arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to your heart muscle.

Plaque narrows the arteries and reduces blood flow to your heart muscle. Reduced blood flow can cause chest pain, especially when you're active. Eventually, an area of plaque can rupture (break open). This causes a blood clot to form on the surface of the plaque.

If the clot becomes large enough, it can block the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the portion of heart muscle fed by the artery. Blocked blood flow to the heart muscle causes a heart attack.

There are many known CHD risk factors. You can control some risk factors, but not others. Risk factors you can control include:

The risk factors you can't control are age, gender, and family history of CHD.

Many people have at least one CHD risk factor. Your risk of CHD and heart attack increases with the number of risk factors you have and their severity. Also, some risk factors put you at greater risk of CHD and heart attack than others. Examples of these risk factors include smoking and diabetes.

Many CHD risk factors start during childhood. This is even more common now because many children are overweight and don't get enough physical activity. Some CHD risk factors can even develop within the first 10 years of life.

Researchers continue to study and learn more about CHD risk factors.

Following a healthy lifestyle can help you and your children prevent or control many CHD risk factors.

Because many lifestyle habits begin during childhood, parents and families should encourage their children to make heart healthy choices. For example, you and your children can lower your risk of CHD if you maintain a healthy weight, follow a healthy diet, do physical activity regularly, and don't smoke.

If you already have CHD, lifestyle changes can help you control your risk factors. This may prevent CHD from worsening. Even if you're in your seventies or eighties, a healthy lifestyle can lower your risk of dying from CHD.

If lifestyle changes aren't enough, your doctor may recommend other treatments to help control your risk factors.

Your doctor can help you find out whether you have CHD risk factors. He or she also can help you create a plan for lowering your risk of CHD, heart attack, and other heart problems.

If you have children, talk with their doctors about their heart health and whether they have CHD risk factors. If they do, ask your doctor to help create a treatment plan to reduce or control these risk factors.

High blood cholesterol is a condition in which your blood has too much cholesterol—a waxy, fat-like substance. The higher your blood cholesterol level, the greater your risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and heart attack.

Cholesterol travels through the bloodstream in small packages called lipoproteins (LI-po-pro-teens). Two major kinds of lipoproteins carry cholesterol throughout your body:

Many factors affect your cholesterol levels. For example, after menopause, women's LDL cholesterol levels tend to rise, and their HDL cholesterol levels tend to fall. Other factors—such as age, gender, diet, and physical activity—also affect your cholesterol levels.

Healthy levels of both LDL and HDL cholesterol will prevent plaque from building up in your arteries. Routine blood tests can show whether your blood cholesterol levels are healthy. Talk with your doctor about having your cholesterol tested and what the results mean.

Children also can have unhealthy cholesterol levels, especially if they're overweight or their parents have high blood cholesterol. Talk with your child's doctor about testing your child' cholesterol levels.

To learn more about high blood cholesterol and how to manage the condition, go to the Health Topics High Blood Cholesterol article.

Triglycerides are a type of fat found in the blood. Some studies suggest that a high level of triglycerides in the blood may raise the risk of CHD, especially in women.

"Blood pressure" is the force of blood pushing against the walls of your arteries as your heart pumps blood. If this pressure rises and stays high over time, it can damage your heart and lead to plaque buildup.

Blood pressure is measured as systolic (sis-TOL-ik) and diastolic (di-a-STOL-ik) pressures. "Systolic" refers to blood pressure when the heart beats while pumping blood. "Diastolic" refers to blood pressure when the heart is at rest between beats.

You most often will see blood pressure numbers written with the systolic number above or before the diastolic number, such as 120/80 mmHg. (The mmHg is millimeters of mercury—the units used to measure blood pressure.)

All levels above 120/80 mmHg raise your risk of CHD. This risk grows as blood pressure levels rise. Only one of the two blood pressure numbers has to be above normal to put you at greater risk of CHD and heart attack.

Often, high blood pressure has no signs or symptoms. However, the condition can be detected using a simple test that involves placing a blood pressure cuff around your arm.

Most adults should have their blood pressure checked at least once a year. If you have high blood pressure, you'll likely need to be checked more often. Talk with your doctor about how often you should have your blood pressure checked.

Children also can develop high blood pressure, especially if they're overweight. Your child's doctor should check your child's blood pressure at each routine checkup.

In children, blood pressure normally rises with age and body size. Newborns often have very low blood pressure numbers, while older teens have numbers similar to adults. The ranges for normal blood pressure and high blood pressure generally are lower for youth than for adults.

Your child should have routine blood pressure checks starting at 3 years of age. To find out whether a child has high blood pressure, a doctor will compare the child's blood pressure numbers to average numbers for his or her age, gender, and height.

Both children and adults are more likely to develop high blood pressure if they're overweight or have diabetes.

For more information about high blood pressure and how to manage the condition, go to the Health Topics High Blood Pressure article.

Diabetes is a disease in which the body's blood sugar level is too high. The two types of diabetes are type 1 and type 2.

In type 1 diabetes, the body's blood sugar level is high because the body doesn't make enough insulin. Insulin is a hormone that helps move blood sugar into cells, where it's used for energy. In type 2 diabetes, the body's blood sugar level is high mainly because the body doesn't use its insulin properly.

Over time, a high blood sugar level can lead to increased plaque buildup in your arteries. Having diabetes doubles your risk of CHD.

Prediabetes is a condition in which your blood sugar level is higher than normal, but not as high as it is in diabetes. If you have prediabetes and don't take steps to manage it, you'll likely develop type 2 diabetes within 10 years. You're also at higher risk of CHD.

Being overweight or obese raises your risk of type 2 diabetes. With modest weight loss and moderate physical activity, people who have prediabetes may be able to delay or prevent type 2 diabetes. They also may be able to lower their risk of CHD and heart attack. Weight loss and physical activity also can help control diabetes.

Even children can develop type 2 diabetes. Most children who have type 2 diabetes are overweight.

Type 2 diabetes develops over time and sometimes has no symptoms. Go to your doctor or local clinic to have your blood sugar levels tested regularly to check for diabetes and prediabetes.

For more information about diabetes and heart disease, go to the Health Topics Diabetic Heart Disease article. For more information about diabetes and prediabetes, go to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases' (NIDDK's) Introduction to Diabetes.

The terms "overweight" and "obesity" refer to body weight that's greater than what is considered healthy for a certain height. More than two-thirds of American adults are overweight, and almost one-third of these adults are obese.

The most useful measure of overweight and obesity is body mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated from your height and weight. In adults, a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is considered normal. A BMI of 25 to 29.9 is considered overweight. A BMI of 30 or more is considered obese.

You can use the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI's) online BMI calculator to figure out your BMI, or your doctor can help you.

Overweight is defined differently for children and teens than it is for adults. Children are still growing, and boys and girls mature at different rates. Thus, BMIs for children and teens compare their heights and weights against growth charts that take age and gender into account. This is called BMI-for-age percentile.

For more information about BMI-for-age percentile, go to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) BMI-for-age calculator.

Being overweight or obese can raise your risk of CHD and heart attack. This is mainly because overweight and obesity are linked to other CHD risk factors, such as high blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

For more information, go to the Health Topics Overweight and Obesity article.

Smoking tobacco or long-term exposure to secondhand smoke raises your risk of CHD and heart attack.

Smoking triggers a buildup of plaque in your arteries. Smoking also increases the risk of blood clots forming in your arteries. Blood clots can block plaque-narrowed arteries and cause a heart attack.

Some research shows that smoking raises your risk of CHD in part by lowering HDL cholesterol levels.

The more you smoke, the greater your risk of heart attack. Studies show that if you quit smoking, you cut your risk of heart attack in half within a year. The benefits of quitting smoking occur no matter how long or how much you've smoked.

Most people who smoke start when they're teens. Parents can help prevent their children from smoking by not smoking themselves. Talk with your child about the health dangers of smoking and ways to overcome peer pressure to smoke.

For more information, including tips on how to quit smoking, go to the Health Topics Smoking and Your Heart article and the NHLBI's "Your Guide to a Healthy Heart."

For more information about children and smoking, go to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') Kids and Smoking Web page and the CDC's Smoking and Tobacco Use Web page.

Inactive people are nearly twice as likely to develop CHD as those who are active. A lack of physical activity can worsen other CHD risk factors, such as high blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels, high blood pressure, diabetes and prediabetes, and overweight and obesity.

It's important for children and adults to make physical activity part of their daily routines. One reason many Americans aren't active enough is because of hours spent in front of TVs and computers doing work, schoolwork, and leisure activities.

Some experts advise that children and teens should reduce screen time because it limits time for physical activity. They recommend that children aged 2 and older should spend no more than 2 hours a day watching TV or using a computer (except for school work).

Being physically active is one of the most important things you can do to keep your heart healthy. The good news is that even modest amounts of physical activity are good for your health. The more active you are, the more you will benefit.

For more information, go to HHS' "2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans," the Health Topics Physical Activity and Your Heart article, and the NHLBI's "Your Guide to Physical Activity and Your Heart."

An unhealthy diet can raise your risk of CHD. For example, foods that are high in saturated and trans fats and cholesterol raise LDL cholesterol. Thus, you should try to limit these foods.

Saturated fats are found in some meats, dairy products, chocolate, baked goods, and deep-fried and processed foods. Trans fats are found in some fried and processed foods. Cholesterol is found in eggs, many meats, dairy products, commercial baked goods, and certain types of shellfish.

It's also important to limit foods that are high in sodium (salt) and added sugars. A high-salt diet can raise your risk of high blood pressure.

Added sugars will give you extra calories without nutrients like vitamins and minerals. This can cause you to gain weight, which raises your risk of CHD. Added sugars are found in many desserts, canned fruits packed in syrup, fruit drinks, and nondiet sodas.

You also should try to limit how much alcohol you drink. Too much alcohol will raise your blood pressure. It also will add calories, which can cause weight gain.

Stress and anxiety may play a role in causing CHD. Stress and anxiety also can trigger your arteries to tighten. This can raise your blood pressure and your risk of heart attack.

The most commonly reported trigger for a heart attack is an emotionally upsetting event, especially one involving anger. Stress also may indirectly raise your risk of CHD if it makes you more likely to smoke or overeat foods high in fat and sugar.

As you get older, your risk of CHD and heart attack rises. This is in part due to the slow buildup of plaque inside your heart arteries, which can start during childhood.

In men, the risk of CHD increases faster after age 45. In women, the risk of CHD increases faster after age 55.

Most people have some plaque buildup in their heart arteries by the time they're in their seventies. However, only about 25 percent of those people have chest pain, heart attacks, or other signs of CHD.

Before age 55, women have a lower risk of CHD than men. This is because before menopause, estrogen provides women some protection against CHD. After age 55, however, the risk of CHD increases similarly in both women and men.

Some risk factors may affect CHD risk differently in women than in men. For example, diabetes raises the risk of CHD more in women.

Also, some risk factors for heart disease only affect women, such as preeclampsia (pre-e-KLAMP-se-ah). Preeclampsia is a condition that can develop during pregnancy. The two main signs of preeclampsia are a rise in blood pressure and excess protein in the urine.

Preeclampsia is linked to an increased lifetime risk of heart disease, including CHD, heart attack, heart failure, and high blood pressure. (Likewise, having heart disease risk factors, such as diabetes or obesity, increases your risk of preeclampsia.)

Family history plays a role in CHD risk. Your risk increases if your father or a brother was diagnosed with CHD before 55 years of age, or if your mother or a sister was diagnosed with CHD before 65 years of age.

However, having a family history of CHD doesn't mean that you will have it too. This is especially true if your affected family member smoked or had other CHD risk factors that were not well treated.

Making lifestyle changes and taking medicines to treat other risk factors often cen lessen genetic influences and stop or slow the progress of CHD.

You can prevent and control many coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors with lifestyle changes and medicines. Examples of these controllable risk factors include high blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, and overweight and obesity. Only a few risk factors—such as age, gender, and family history—can't be controlled.

To reduce your risk of CHD and heart attack, try to control each risk factor you can. The good news is that many lifestyle changes help control several CHD risk factors at the same time. For example, physical activity may lower your blood pressure, help control diabetes and prediabetes, reduce stress, and help control your weight.

Many lifestyle habits begin during childhood. Thus, parents and families should encourage their children to make heart healthy choices, such as following a healthy diet and being physically active. Make following a healthy lifestyle a family goal.

To achieve this goal, you should learn about key health measures, such as weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and your child's BMI-for-age percentile. For more information about BMI in adults and children, go to "Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors."

Be aware of your and your family members' blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. Once you know these numbers, you can work to bring them into, or keep them within, a healthy range.

Making lifestyle changes can be hard. But if you make these changes as a family, it may be easier for everyone to prevent or control their CHD risk factors.

For tips on how to help your children adopt healthy habits, visit the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI's) We Can!® Ways to Enhance Children's Activity & Nutrition Web site.

A healthy lifestyle can lower the risk of CHD. If you already have CHD, a healthy lifestyle may prevent it from getting worse. A healthy lifestyle includes:

A healthy diet is an important part of a healthy lifestyle. To lower your risk of CHD and heart attack, you and your family should follow a diet that is:

Research suggests that drinking small to moderate amounts of alcohol regularly also can lower your risk of CHD. One drink a day can lower your risk by raising your high-density lipoprotein (HDL), or "good," cholesterol level. One drink is a glass of wine, beer, or a small amount of hard liquor.

If you don't drink, this isn't a recommendation to start using alcohol. If you're pregnant, if you're planning to become pregnant, or if you have another health condition that could make alcohol use harmful, you shouldn't drink.

Also, too much alcohol can cause you to gain weight and raise your blood pressure and triglyceride level. In women, even one drink a day may raise the risk of certain types of cancer.

Teach your children how to make healthy food choices. For example, have them help you shop for and make healthy foods. Set a good example by following the same heart healthy diet that you ask your children to follow.

For more information about following a healthy diet, go to the NHLBI's Aim for a Healthy Weight Web site, "Your Guide to a Healthy Heart," "Your Guide to Lowering Your Blood Pressure With DASH," and "Your Guide to Lowering Your Cholesterol With TLC." All of these resources provide general information about healthy eating.

You don't have to be an athlete to lower your risk of CHD. You can benefit from as little as 60 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week.

For major health benefits, adults should do at least 150 minutes (2.5 hours) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity each week.

Another option is to do a combination of both. A general rule is that 2 minutes of moderate-intensity activity counts the same as 1 minute of vigorous-intensity activity.

The more active you are, the more you'll benefit. If you're obese, or if you haven't been active in the past, start physical activity slowly and build up the intensity over time.

Children and youth should do 60 minutes or more of physical activity every day. A great way to encourage physical activity is to do it as a family. You also may want to limit your children's TV, video, and computer time to encourage them to be more active.

If you have CHD or symptoms such as chest pain and dizziness, talk with your doctor before you start a new exercise plan. Find out how much and what kinds of physical activity are safe for you. Avoid exercising outdoors when air pollution levels are high or the temperature is very hot or cold.

For more information about physical activity, go to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') "2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans," the Health Topics Physical Activity and Your Heart article, and the NHLBI's "Your Guide to Physical Activity and Your Heart."

Following a healthy diet and being physically active can help you maintain a healthy weight. Controlling your weight helps you control CHD risk factors.

If you're overweight or obese, try to lose weight. A loss of just 5 to 10 percent of your current weight can lower your risk of CHD.

To lose weight, cut back your calorie intake and do more physical activity. Eat smaller portions and choose lower calorie foods. Don't feel that you have to finish the entrees served at restaurants. Many restaurant portions are oversized and have too many calories for the average person.

For overweight children and teens, slowing the rate of weight gain is important. However, reduced-calorie diets aren't advised, unless approved by a doctor.

If you smoke, quit. Smoking can raise your risk of CHD and heart attack and worsen other CHD risk factors. Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit smoking. Also, try to avoid secondhand smoke.

If you have trouble quitting smoking on your own, consider joining a support group. Many hospitals, workplaces, and community groups offer classes to help people quit smoking.

You can help your children avoid smoking or quit smoking. Talk with them about the health effects of smoking. Teach them how to handle peer pressure to smoke.

Teens who have parents who smoke are more likely to smoke themselves. Set a good example by not smoking or quitting smoking. Set firm rules about no tobacco use in your home.

If you have a child who smokes, help him or her create a plan to quit. Offer your child information and resources on how to quit. Stress the natural rewards that come with quitting, such as freedom from addiction, better fitness and sports performance, and improved appearance. Reinforce the decision to quit with praise.

For more information about how to quit smoking, go to the Health Topics Smoking and Your Heart article and the NHLBI's "Your Guide to a Healthy Heart."

For more information about children and smoking, go to HHS' Kids and Smoking Web page and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Smoking and Tobacco Use Web page.