Chicken and Other Poultry

For information on preparing and storing turkey, see Turkey.

For information on preparing and storing turkey, see Turkey.

The Color of Meat and Poultry (USDA)

Why are there differences in the color and what do they mean?

Hock Locks and Other Accoutrements (USDA)

What happens if you cook poultry with the metal, plastic, paper, or other items in the packaging?

Poultry: Basting, Brining, and Marinating (USDA)

Safety tips for basting, brining, and marinating poultry.

The Poultry Label Says "Fresh" (USDA)

Understanding the difference between fresh and frozen poultry

Water in Meat and Poultry (USDA)

Answers to questions about water in packages of fresh meat and poultry.

Meat and Poultry Roasting Chart

Details on oven temperatures, timing, and safe minimum internal temperatures for a variety of meats.

For versions of these fact sheets in PDF format and en Español, see Poultry Preparation (USDA).

|

Type of Poultry

|

Resources

|

|

Chicken

|

Chicken From Farm to Table (USDA)

Safe storage, handling, cooking methods and times for chicken.

|

|

Duck

|

Duck and Goose from Farm to Table (USDA)

Safe storage, handling, cooking methods, and cooking times for duck.

|

|

Emu

|

Ratites (Emu, Ostrich, and Rhea) (USDA)

Safe storage, handling, and cooking methods for these birds.

|

|

Game Birds

|

Food Safety of Farm-Raised Game (USDA)

Learn about safe handling of partridge, quail, pheasant, and other game birds.

|

|

Giblets

|

Giblets and Food Safety (USDA)

Inspection, processing, safe handling, and cooking of poultry giblets.

|

|

Goose

|

Duck and Goose from Farm to Table (USDA)

Safe storage, handling, cooking methods and times for goose.

|

|

Ground Poultry

|

Ground Poultry and Food Safety (USDA)

Labeling, storage, and cooking of ground poultry.

|

|

Ostrich

|

Ratites (Emu, Ostrich, and Rhea) (USDA)

Safe storage, handling, and cooking methods for these birds.

|

|

Rhea

|

Ratites (Emu, Ostrich, and Rhea) (USDA)

Safe storage, handling, and cooking methods for these birds.

|

Seafood

Fish and shellfish are an important part of a healthful diet. In fact, a well-balanced diet that includes a variety of fish and shellfish can contribute to heart health and children's growth and development. But, as with any type of food, it's important to handle seafood safely in order to reduce the risk of foodborne illness.

Fresh and Frozen Seafood: Selecting and Serving it Safely

Mercury in Seafood

What You Need to Know About Mercury in Fish and Shellfish (FDA)

Advice for pregnant women (and those thinking about pregnancy), nursing mothers, and young children.

Risks of Eating Raw Oysters

Raw Oyster Myths (FDA)

Hot sauce does not kill harmful bacteria in raw oysters; neither does alcohol. Get the facts behind the myths.

Raw Oysters Contaminated With Vibrio vulnificus Can Cause Illness and Death (FDA)

Explains the risks associated with eating raw oysters and how to prevent serious illness.

General Information on Seafood

Fresh and Frozen Seafood: Selecting and Serving it Safely (FDA)

How to handle seafood safely in order to reduce the risk of foodborne illness.

Seafood Questions and Answers (FDA)

Selecting safe seafood, figuring out if a fish is fresh, spotting a safe seafood seller, and more.

Cooperative Program Ensures Safe Shellfish (FDA)

How industry and government work together to keep shellfish safe.

See the slideshow or read the article

Eggs and Egg Products

Eggs are one of nature's most nutritious and economical foods. But, you must take special care with handling and preparing fresh eggs and egg products to avoid food poisoning.

Egg Basics

Thorough cooking is an important step in making sure eggs are safe.

-

Scrambled eggs: Cook until firm, not runny.

-

Fried, poached, boiled, or baked: Cook until both the white and the yolk are firm.

-

Egg mixtures, such as casseroles: Cook until the center of the mixture reaches 160 °F when measured with a food thermometer.

Egg Recipes: Playing It Safe

-

Homemade ice cream and eggnog are safe if you do one of the following:

-

Dry meringue shells, divinity candy, and 7-minute frosting are safe — these are made by combining hot sugar syrup with beaten egg whites. However, avoid icing recipes using uncooked eggs or egg whites.

-

Meringue-topped pies should be safe if baked at 350 °F for about 15 minutes. But avoid chiffon pies and fruit whips made with raw, beaten egg whites — instead, substitute pasteurized dried egg whites, whipped cream, or a whipped topping.

-

Adapting Recipes: If your recipe calls for uncooked eggs, make it safe by doing one of the following:

-

Heating the eggs in one of the recipe’s other liquid ingredients over low heat, stirring constantly, until the mixture reaches 160 °F. Then, combine it with the other ingredients and complete the recipe. Or use pasteurized eggs or egg products.

-

Using pasteurized eggs or egg products.

Note: Egg products, such as liquid or frozen egg substitute, are pasteurized, so it’s safe to use them in recipes that will be not be cooked. However, it’s best to use egg products in a recipe that will be cooked, especially if you are serving pregnant women, babies, young children, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems.

General Information

Egg Storage Chart

Details on refrigerating and freezing raw eggs, cooked eggs, and egg dishes.

Egg Safety and Eating Out

Practical things that you can do to keep your family safe.

Tips to Reduce Your Risk of Salmonella from Eggs (CDC)

If eggs are eaten raw or undercooked, Salmonella bacteria can cause illness.

Playing it Safe With Eggs: What Consumers Need to Know (FDA)

How to buy, cook, serve, store, and transport fresh eggs to avoid salmonella poisoning. From Consumer Information about Egg Safety.

Egg Products and Food Safety (USDA)

How to use liquid, frozen, and dried egg products safely.

Shell Eggs from Farm to Table (USDA)

Answers to questions on eggs, from how often a hen lays an egg to the safety of Easter eggs to egg storage guidelines.

Milk, Cheese, and Dairy Products

Myths About Raw Milk

Pasteurization is a process that kills harmful bacteria by heating milk to a specific temperature for a set period of time. Some people continue to believe that pasteurization harms milk and that raw milk is a safe healthier alternative.

Pasteurization is a process that kills harmful bacteria by heating milk to a specific temperature for a set period of time. Some people continue to believe that pasteurization harms milk and that raw milk is a safe healthier alternative.

Raw milk can harbor dangerous microorganisms, such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, that can pose serious health risks to you and your family.

Here are some common myths and proven facts about milk and pasteurization:

-

Raw milk DOES NOT kill dangerous pathogens by itself.

-

Pasteurizing milk DOES NOT cause lactose intolerance and allergic reactions. Both raw milk and pasteurized milk can cause allergic reactions in people sensitive to milk proteins.

-

Pasteurization DOES NOT reduce milk's nutritional value.

-

Pasteurization DOES NOT mean that it is safe to leave milk out of the refrigerator for extended time,particularly after it has been opened.

-

Pasteurization DOES kill harmful bacteria.

-

Pasteurization DOES save lives.

Food Safety and Raw Milk (CDC)

Comprehensive information on the dangers of raw milk, including:

The Dangers of Raw Milk (FDA)

Raw milk can harbor dangerous microorganisms that can pose serious health risks.

Questions & Answers: Raw Milk (FDA)

Raw milk is not safe to drink. Find out more about the risks.

Raw Milk May Pose Health Risk (FDA)

Consumer update on raw milk

Raw Milk Misconceptions and the Danger of Raw Milk Consumption (FDA)

Point and counterpoint on popular myths about raw milk

The Dangers of Raw Milk (FDA)

Unpasteurized milk can pose a serious health risk

Food Safety and Raw Milk (FDA)

Understanding health risks associated with raw milk.

Raw Milk Questions and Answers

Frequently asked questions and answers about the risks of drinking raw milk.

Cheese

Preventing Listeriosis In Pregnant Hispanic Women in the U.S. (FDA)

When pregnant women eat Mexican-style soft cheeses, they are putting their unborn babies at risk!

Ice Cream

Enjoying Homemade Ice Cream without the Risk of Salmonella Infection (FDA)

To avoid the risk of salmonella infection, use a pasteurized egg product instead of raw eggs.

Nuts, Grains, and Beans

Nuts, grains, beans, and other legumes, and their by-products, are found in a wide variety of foods. Since these foods are ingredients in so many food products, contamination or mislabeling of allergens can pose a widespread risk.

Nuts, grains, beans, and other legumes, and their by-products, are found in a wide variety of foods. Since these foods are ingredients in so many food products, contamination or mislabeling of allergens can pose a widespread risk.

Contamination may come from harmful bacteria such as salmonella, some foods in these categories, particularly grains, are also susceptible to chemical environmental risks.

Several of these foods – including tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans – have been classified as major food allergens by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The law requires that all foods are labeled with their ingredients, and that labels clearly identify any of the major food allergens or their protein derivatives.

Learn more by referring to the resources below.

Risks and Contamination

Arsenic in Rice (FDA) The U.S. Food and Drug Administration shares important information on the presence of arsenic, a chemical associated with long-term health effects, in rice. Find out what you should do, and what steps the FDA is taking.

Salmonella in Peanut Butter (CDC) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the presence of Salmonella bacteria in certain samples of peanut butter and other nut products beginning September 2012. Find details about their investigation and read their advice to consumers.

Recalled Peanut Product Database (FDA) Search this database to learn if any peanut products in your pantry have been affected by the multi-state Salmonella outbreak.

2009 Peanut Product Recall (FDA) In March 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration requested a recall on certain products containing peanuts due to a contamination threat. Find details about the investigation and read advice to consumers.

General Allergy Information

Food Allergy Information (FDA) Learn about major food allergens, labeling, and what to do if symptoms occur.

Flour, Raw Dough, and Raw Batter

Flour Safety Basics

-

Do not eat or play with flour, raw dough  , or raw batter that is intended to be cooked.

, or raw batter that is intended to be cooked.

-

Do not use flour in items that are not intended to be cooked.

-

If you or someone you are cooking for has a food allergy, carefully check the labels of any flour or baking mixes you plan to use.

People often understand that it is dangerous to eat raw eggs because of the risk of Salmonella, but eggs aren’t the only potential carrier of foodborne illness in raw dough or batter. Raw flour may be contaminated with harmful bacteria such as E. coli.

Flour can be made from a variety of grains, nuts, and legumes including wheat, soy, tree nuts, and peanuts, all four of which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration classifies as major food allergens. Manufacturers are legally required to list ingredients and clearly identify any major allergens (or their protein derivatives) on the labels of food products.

Cooking with Flour

Throw out recalled products

-

Although CDC closed its investigation into the E. coli outbreak, continued illness from recalled products is expected due to the long shelf life of flour and baking mixes.

-

Check CDC’s recall page  that lists all affected products. Throw out any flour or baking mixes on the recall list.

that lists all affected products. Throw out any flour or baking mixes on the recall list.

-

If you stored recalled flour in a reusable container, be sure to thoroughly wash and sanitize the container before using it again.

-

If you are unsure if the flour is included in the recall, throw out the product.

Separate flour, raw dough, or raw batter

-

Keep raw foods, including any flour products, separate from other foods while preparing them to prevent cross-contamination before cooking.

-

Use separate bowls, measuring cups, and utensils for flour, raw dough, and raw batter.

Bake it before you bite it

-

Do not eat or play with flour, raw dough, or raw batter.

-

Do not add flour to foods that will not be cooked, such as milkshakes, ice-cream mixes.

-

Do not taste flour, raw dough, or raw batter. Eating even a small amount can make you sick.

-

Bake/cook items containing flour, raw dough, or raw batter thoroughly before eating them, including flour used for thickening.

-

Follow package directions on mixes for proper cooking temperatures and times.

Keep it cool and clean

-

Refrigerate baked goods containing fillings (such as cream) promptly after making or purchasing them to prevent illness-causing bacteria from growing.

-

Wash any bowls, utensils, and other surfaces that were used when baking with hot water and soap. The surfaces to be cleaned may extend beyond the immediate work area, because flour is powdery and tends to spread.

-

Wash your hands with water and soap after baking.

Baby Food and Infant Formula

Infants and young children are particularly vulnerable to foodborne illness because their immune systems are not developed enough to fight off infections. That's why extra care should be taken when handling and preparing their food and formula.

Baby Food

The most important action that you can take to prevent foodborne illness in your babies and children is to wash your hands. Your hands can pick up harmful bacteria from pets, raw foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs), soil, and diapers.

The most important action that you can take to prevent foodborne illness in your babies and children is to wash your hands. Your hands can pick up harmful bacteria from pets, raw foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs), soil, and diapers.

Always wash your hands:

-

Before and after handling food

-

After using the bathroom, changing diapers, or handling pets.

Other ways to keep your baby’s food safe:

-

Check the packaging of commercial baby food before serving: The following may indicate that the food is contaminated or at risk of bacterial contamination:

-

For jars: Make sure that the safety button on the lid is down. Discard any jars that don’t “pop” when opened or that have chipped glass or rusty lids.

-

For plastic pouches: Discard any packages that are swelling or leaking.

-

Don’t “double dip” with baby food: Never put baby food in the refrigerator if the baby doesn’t finish it. Your best bet: Don’t feed your baby directly from the jar of baby food. Instead, put a small serving of food on a clean dish and refrigerate the remaining food in the jar. If the baby needs more food, use a clean spoon to serve another portion. Throw away any food in the dish that’s not eaten. If you do feed a baby from a jar, always discard any remaining food.

-

Don’t share spoons: Don’t put the baby’s spoon in your mouth or anyone else’s mouth – or vice versa. If you want to demonstrate eating for your baby, get a separate serving dish and spoon for yourselv.

-

Never leave any open containers of liquid or pureed baby food out at room temperature for more than two hours: Harmful bacteria grows rapidly in food at room temperature.

-

Store opened baby food in the refrigerator for no more than three days: If you’re not sure that the food is safe, remember this saying: “If in doubt, throw it out.”

General Information on Baby Food

Once Baby Arrives: Food Safety for Moms-to-Be (FDA)

Do’s and don’ts for feeding your baby, plus tips on microwaving baby food and when to call the doctor.

Infant Formula

If you’re the parent or caretaker of an infant, you’ve probably heard that breast milk is the best source of nutrition for infants. In situations in which it’s not possible to breastfeed an infant, you may choose to use a commercially prepared infant formula.

If you’re the parent or caretaker of an infant, you’ve probably heard that breast milk is the best source of nutrition for infants. In situations in which it’s not possible to breastfeed an infant, you may choose to use a commercially prepared infant formula.

Why can’t I give my baby cow’s milk?

Cow's milk by itself is not appropriate for infants less than 1 year old. Cow’s milk does not have the correct balance of nutrients for infants to grow and develop normally, and it can cause problems with anemia and kidney function.

Raw milk is never appropriate for infants – or anyone else. It should not be consumed by anyone at any time for any purpose. Raw milk can harbor dangerous microorganisms, such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, that can pose serious health risks.

But isn’t formula made from cow’s milk?

Most infant formula is made with cow's milk, but it has been modified and supplemented with additional nutrients. As a result, the formula is more nutritious and easier for the baby to digest than cow’s milk. Other formula options include soy-based formulas and hypoallergenic (or protein hydrolysate and amino acid-based) formulas. Special formulas are available for babies who are premature or have other health problems.

How does the government regulate infant formula?

The FDA does not approve infant formulas before they can be marketed. All formulas marketed in the United States, however, must meet Federal nutrient requirements. The FDA also monitors infant formula, which means that it inspects facilities that manufacture formula and analyzes samples.

What can I do to make sure that formula is safe for my baby?

Here are a few basic steps that you can follow to ensure that formula is safe from bacteria that can cause illness.

-

Prepare safe water for mixing: Bring tap water to a roiling boil and boil it for one minute. If you use bottled water, follow this same process unless the label indicates that it is sterile. Then, cool the water quickly to body temperature before mixing the formula.

-

Use clean bottles and nipples: You may want to sterilize bottles and nipples before first use. After that, it’s safe to wash them by hand or in a dishwasher.

-

Don't make more formula than you will need: Formula can become contaminated during preparation, and bacteria can multiply quickly if formula is improperly stored. Your best bet: prepare formula in smaller quantities on an as-needed basis to greatly reduce the possibility of contamination. And always follow the label instructions for mixing formula.

General Information on Infant Formula

Infant Formulas (NIH MedlinePlus)

Trusted information on types of formula, recommendations, and side effects of improper use.

FDA 101: Infant Formula (FDA)

The basics on types of formula, along with safety tips and instructions for reporting problems.

Safe Preparation, Storage and Handling of Powdered Infant Formula (World Health Organization)

Guidelines on infant formula in English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Arabic, and Japanese.

Pet Food

Many people don’t realize that the basic principles of food safety apply to their pets’ foods too. For example, pet food or treats contaminated with Salmonella can cause infections in dogs and cats. And contaminated pet food that is not handled properly can cause serious illness in people too, especially children.

Many people don’t realize that the basic principles of food safety apply to their pets’ foods too. For example, pet food or treats contaminated with Salmonella can cause infections in dogs and cats. And contaminated pet food that is not handled properly can cause serious illness in people too, especially children.

If you’re a pet owner, one of the most important things you can do to keep your pets, your family, and yourself safe from foodborne illness is to wash your hands:

-

Before and after handling pet foods and treats, wash your hands for 20 seconds with hot running water and soap. (Tip: Sing “Happy Birthday” twice to time yourself.)

-

After petting, touching, handling, or feeding your pet, and especially after contact with feces, wash your hands for 20 seconds.

-

Wash hands before preparing your own food and before eating.

Because infants and children are especially susceptible to foodborne illness, keep them away from areas where you feed your pets. Never allow them to touch or eat pet food.

General Information

Safe Handling Tips for Pet Foods and Treats (FDA)

Safe Handling Tips for Pet Foods and Treats (FDA)

Pets can get food poisoning, too. How to buy, prepare, and store pet food to avoid contamination.

Pet Food (FDA)

Details on how the FDA ensures that pet foods are properly labeled and contain safe ingredients.

FDA 101: Animal Feed (FDA)

Yes: Pet food, including dry and canned food and pet treats, is considered animal feed.

How to Report a Pet Food Complaint (FDA)

Before you contact the FDA, review this checklist on the pet food product and any symptoms your pet may have.

Think Food Safety (FDA)

We know to wash our hands before eating dinner and after using the bathroom, but what about after handling pet food?

Salmonella and Dry Pet Food

Salmonella from Dry Pet Food and Treats (CDC)

Follow these tips to help prevent an infection with Salmonella from handling dry pet food and treats.

Podcast: Tips to Reduce Your Risk of Getting a Salmonella Infection from Dry Pet Food

Listen to the podcast or read the script (2:56 minutes)

Concerns Related to Specific Recalls

Check the Food Safety widget to get the latest recalls on pet food and animal feed, as well as other food recalls.

Melamine Pet Food Recall of 2007 (FDA)

Certain pet foods contaminated with melamine were sickening and killing cats and dogs in 2007.

Caution to Dog Owners About Chicken Jerky Products (FDA)

Chicken jerky products such as chicken tenders, strips, or treats may cause illnesses in dogs.

Questions and Answers: Human Illness (Salmonella) Associated with Dry Pet Food (CDC)

In 2007, Salmonella linked to dry pet food sickened 62 people in 18 states.

https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep/types/petfood/index.html

For information on preparing and storing turkey, see

For information on preparing and storing turkey, see

Pasteurization is a process that kills harmful bacteria by heating milk to a specific temperature for a set period of time. Some people continue to believe that pasteurization harms milk and that raw milk is a safe healthier alternative.

Pasteurization is a process that kills harmful bacteria by heating milk to a specific temperature for a set period of time. Some people continue to believe that pasteurization harms milk and that raw milk is a safe healthier alternative.

Nuts, grains, beans, and other legumes, and their by-products, are found in a wide variety of foods. Since these foods are ingredients

Nuts, grains, beans, and other legumes, and their by-products, are found in a wide variety of foods. Since these foods are ingredients

The most important action that you can take to prevent foodborne illness in your babies and children is to wash your hands. Your hands can pick up harmful bacteria from pets, raw foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs), soil, and diapers.

The most important action that you can take to prevent foodborne illness in your babies and children is to wash your hands. Your hands can pick up harmful bacteria from pets, raw foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs), soil, and diapers. If you’re the parent or caretaker of an infant, you’ve probably heard that breast milk is the best source of nutrition for infants. In situations in which it’s not possible to breastfeed an infant, you may choose to use a commercially prepared infant formula.

If you’re the parent or caretaker of an infant, you’ve probably heard that breast milk is the best source of nutrition for infants. In situations in which it’s not possible to breastfeed an infant, you may choose to use a commercially prepared infant formula. Many people don’t realize that the basic principles of food safety apply to their pets’ foods too. For example, pet food or treats contaminated with Salmonella can cause infections in dogs and cats. And contaminated pet food that is not handled properly can cause serious illness in people too, especially children.

Many people don’t realize that the basic principles of food safety apply to their pets’ foods too. For example, pet food or treats contaminated with Salmonella can cause infections in dogs and cats. And contaminated pet food that is not handled properly can cause serious illness in people too, especially children. Safe Handling Tips for Pet Foods and Treats

Safe Handling Tips for Pet Foods and Treats

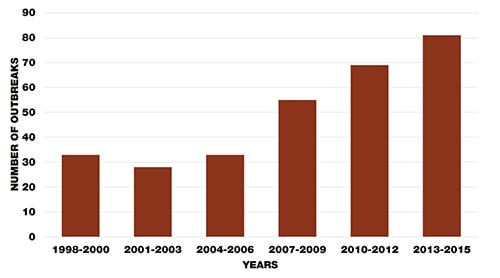

CDC has conducted two studies that show an increase in the number of raw milk-associated outbreaks as more states have allowed the legal sale of raw (unpasteurized) milk.

Increased Outbreaks Associated with Nonpasteurized Milk, United States, 2007–2012

This more recent study reviewed outbreaks linked to raw milk in the United States. The study analyzed the number of outbreaks; the legal status of raw milk sales in each state; and the number of illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths associated with these outbreaks.

What were the findings of this study?

From 2007 through 2012, 26 states reported 81 outbreaks linked to raw milk. The outbreaks caused 979 illnesses and 73 hospitalizations.

From 2007 through 2009, 30 outbreaks were linked to raw milk. This increased to 51 outbreaks from 2010 through 2012.

Among outbreaks in which the food or drink linked to the outbreak was identified, the percentage associated with raw milk increased from 2% from 2007 through 2009 to 5% from 2010 through 2012.

Three germs caused most raw milk outbreaks from 2007 through 2012:

Campylobacter caused 81% of outbreaks. The number of Campylobacter infections from raw milk nearly doubled in the 6-year period.

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli caused 17% of outbreaks.

Salmonella caused 3% of outbreaks.

The average number of outbreaks linked to raw milk each year was four times higher from 2007 through 2012 than from 1993 through 2006.

59% of outbreaks involved at least one child younger than 5.

In raw milk outbreaks, children aged 1 to 4 accounted for 38% of illnesses caused by Salmonella and 28% of illnesses caused by Shiga toxin-producing E. coli

[PDF – 1 page] [text version]

Find out the current legal status of the sale of raw milk in D.C. and all 50 states >

81% of outbreaks were reported in states where the sale of raw milk was legal.

In 2004, the sale of raw milk was legal in some form in 22 states. This number increased to 30 in 2011.

The number of states allowing cow-share programs – in which a person buys part ownership of a cow in return for the milk produced – increased from 5 in 2004 to 10 in 2008.

Where do people buy raw milk?

Dairy farms: farms that keep cows for milk production

Licensed/commercial sellers: farms or stores separate from a farm

Cow share or herd share: buyers pay farmers a fee to care for a cow in exchange for a percentage of the milk that is produced

Buying club: a group of people who purchase food (including dairy products) from farmers at discounted prices

The raw milk that caused outbreaks came from:

The dairy farm directly, 71% of the time

Licensed or commercial milk sellers, 13% of the time

A cow share or herd share, 12% of the time

Although raw milk is not included in interstate commerce (across state lines), some states allow sales within their borders.

In a 2011 outbreak of Campylobacter infections in North Carolina, where sales were prohibited, raw milk was purchased from a “buying club” in South Carolina where sales were legal.

In a 2012 outbreak of Campylobacter infections in Pennsylvania, where raw milk sales were legal, cases were reported from Maryland, West Virginia, and New Jersey, where sales were prohibited.

More information:

Find out about a 2016 outbreak of Listeria infections in Florida and California in which raw milk was purchased from a buying club in Pennsylvania where sales were legal >

Nonpasteurized (Raw) Dairy Products, Disease Outbreaks, and State Laws—United States, 1993–2006

A previous study reviewed outbreaks linked to dairy products. The study compared outbreaks linked to raw (unpasteurized) dairy products and outbreaks linked to pasteurized dairy products in terms of the types of infection; the numbers of outbreaks, illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths; and age and sex of the ill people in the outbreaks. This study also compared the number of outbreaks linked to raw dairy products in states that allowed the sale of raw dairy products to the number in states that prohibited the sale of these products.

What were the findings of this study?

From 1993 through 2006, 121 outbreaks were linked to dairy products identified as pasteurized or unpasteurized (raw). These outbreaks resulted in 4,413 illnesses, 239 hospitalizations, and 3 deaths.

73 outbreaks (46 from fluid milk and 27 from cheese) were linked to raw milk, and 48 outbreaks (10 from fluid milk and 38 from cheese) were linked to pasteurized milk.

Probably no more than 1% of the milk consumed in the United States is raw, yet more outbreaks were linked to raw milk than by pasteurized milk.

If you consider the number of outbreaks associated with raw milk in light of the very small amount of milk that is consumed raw, the risk of outbreaks linked to raw milk is at least 150 times greater than the risk of outbreaks linked to pasteurized milk.

The hospitalization rate for patients in outbreaks linked to raw milk was 13 times higher (13% vs. 1%) than the rate for people in outbreaks linked to pasteurized milk.

This difference is partly because the outbreaks linked to raw milk were all caused by bacterial infections, which can be severe. For example, E. coli O157:H7, which can cause kidney failure and death, was a common cause of outbreaks linked to raw milk. Relatively mild viral infections and toxins were common causes of outbreaks linked to pasteurized milk.

From 1993 through 2006, 60% of people sickened in outbreaks linked to raw milk were younger than 20. Only 23% of people in outbreaks linked to pasteurized milk were younger than 20.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and many other professional organizations advise against feeding raw milk products to children.

From 1993 through 2006, 55 outbreaks—or 75%—linked to raw milk occurred in states where it was legal to sell raw milk products.

The rate of outbreaks linked to raw fluid milk is more than twice as high in states that allow the sale of raw milk than in states than do not allow its sale.

The rate of outbreaks linked to cheese made from raw milk is nearly six times as high in states that allow the sale of raw milk than in states that do not allow its sale.

Restricting the sale of raw milk products reduces outbreaks linked to raw milk.

These studies indicate that outbreaks from raw milk continue to threaten the public’s health. You should only consume pasteurized milk and milk products. Look for the word “pasteurized” on product labels.