Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are also called sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs. STIs are usually spread by having vaginal, oral, or anal sex. More than 9 million women in the United States are diagnosed with an STI each year. Women often have more serious health problems from STIs than men, including infertility. (OWH, HHS)

Sexually Transmitted Infections/Diseases

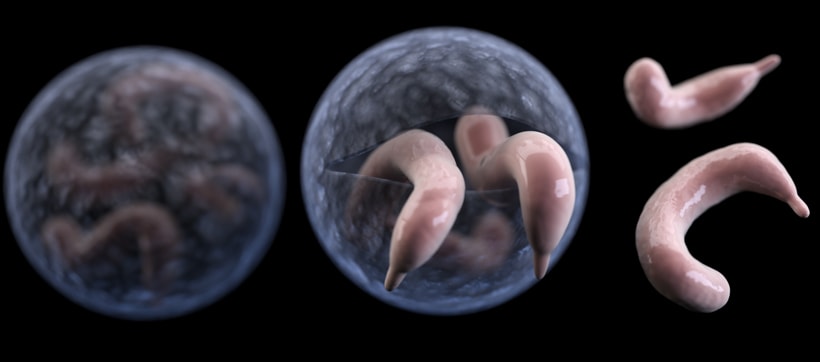

CONDITION: Amebiasis

Amebiasis is an infection of the intestines caused by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica.

Causes

Entamoeba histolytica can live in the large intestine (colon) without causing damage to the intestine. In some cases, it invades the colon wall, causing colitis, acute dysentery, or long-term (chronic) diarrhea. The infection can also spread through the blood to the liver. In rare cases, it can spread to the lungs, brain, or other organs.

This condition occurs worldwide. It is most common in tropical areas that have crowded living conditions and poor sanitation. Africa, Mexico, parts of South America, and India have major health problems due to this disease.

Entamoeba histolytica is spread through food or water contaminated with stools. This contamination is common when human waste is used as fertilizer. It can also be spread from person to person, particularly by contact with the mouth or rectal area of an infected person.

Risk factors for severe amebiasis include:

- Alcoholism

- Cancer

- Malnutrition

- Older or younger age

- Pregnancy

- Recent travel to a tropical region

- Use of corticosteroid medication to suppress the immune system

In the United States, amebiasis is most common among those who live in institutions or people who have traveled to an area where amebiasis is common.

Symptoms

Most people with this infection do not have symptoms. If symptoms occur, they are seen 7 to 28 days after being exposed to the parasite.

Mild symptoms:

- Abdominal cramps

- Diarrhea: Passage of 3 to 8 semiformed stools per day, or passage of soft stools with mucus and occasional blood

- Fatigue

- Excessive gas

- Rectal pain while having a bowel movement (tenesmus)

- Unintentional weight loss

Severe symptoms may include:

- Abdominal tenderness

- Bloody stools, including passage of liquid stools with streaks of blood, passage of 10 to 20 stools per day

- Fever

- Vomiting

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will perform a physical exam. You will be asked about your medical history, especially if you have recently traveled overseas.

Examination of the abdomen may show liver enlargement or tenderness in the abdomen.

Tests that may be ordered include:

- Blood test for amebiasis

- Examination of the inside of the lower large bowel (sigmoidoscopy)

- Stool test

- Microscope examination of stool samples, usually with multiple samples over several days

Treatment

Treatment depends on how severe the infection is. Usually, antibiotics are prescribed.

If you are vomiting, you may need to receive medicines through a vein (intravenously) until you can take them by mouth. Medicines to stop diarrhea are usually not prescribed, because they can make the condition worse.

After antibiotic treatment, your stool will likely be rechecked to make sure the infection has been cleared.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Outcome is usually good with treatment. Usually, the illness lasts about 2 weeks, but it can come back if you do not get treated.

Possible Complications

- Liver abscess

- Medication side effects, including nausea

- Spread of the parasite through the blood to the liver, lungs, brain, or other organs

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your health care provider if you have diarrhea that does not go away or gets worse.

Prevention

When traveling in countries where sanitation is poor, drink purified or boiled water. Do not eat uncooked vegetables or unpeeled fruit.

Alternative Names

Amebic dysentery; Intestinal amebiasis.

Source: MedlinePlus, NLM,NIH

- What is bacterial vaginosis (BV)?

- What causes BV?

- What are the signs of BV?

- How can I find out if I have BV?

- How is BV treated?

- Is it safe to treat pregnant women who have BV?

- Can BV cause health problems?

- How can I lower my risk of BV?

- More information on bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis or BV for short is when the natural balance of the friendly bacteria in the vagina is altered and they overgrow. This typically leads to a foul smelling or fishy discharge. Women with BV have higher numbers of undesirable bacteria and correspondingly fewer of other normal protective bacteria. By WomensHealthcare

Bacterial vaginosis

The vagina normally has a balance of mostly "good" bacteria and fewer "harmful" bacteria. Bacterial vaginosis, known as BV, develops when the balance changes. With BV, there is an increase in harmful bacteria and a decrease in good bacteria. BV is the most common vaginal infection in women of childbearing age.

What causes BV?

Not much is known about how women get BV. Any woman can get BV. But there are certain things that can upset the normal balance of bacteria in the vagina, raising your risk of BV:

- Having a new sex partner or multiple sex partners

- Douching

- Using an intrauterine device (IUD) for birth control

- Not using a condom

BV is more common among women who are sexually active, but it is not clear how sex changes the balance of bacteria. You cannot get BV from:

- Toilet seats

- Bedding

- Swimming pools

- Touching objects around you

What are the signs of BV?

Women with BV may have an abnormal vaginal discharge with an unpleasant odor. Some women report a strong fish-like odor, especially after sex. The discharge can be white (milky) or gray. It may also be foamy or watery. Other symptoms may include burning when urinating, itching around the outside of the vagina, and irritation. These symptoms may also be caused by another type of infection, so it is important to see a doctor. Some women with BV have no symptoms at all.

How can I find out if I have BV?

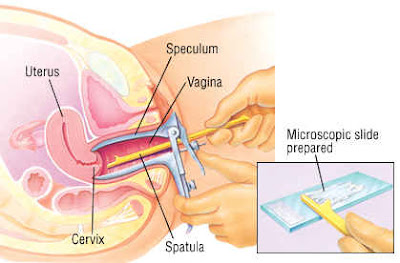

There is a test to find out if you have BV. Your doctor takes a sample of fluid from your vagina and has it tested. Your doctor may also see signs of BV during an examination of the vagina. To help your doctor find the signs of BV or other infections:

- Schedule the exam when you do not have your period.

- Don't douche for at least 24 hours before seeing your doctor. Experts suggest that women do not douche at all.

- Don't use vaginal deodorant sprays. They might cover odors that are important for diagnosis. It may also lead to irritation.

- Don't have sex or put objects, such as a tampon, in your vagina for at least 24 hours before going to the doctor.

How is BV treated?

BV is treated with antibiotic medicines prescribed by your doctor. Your doctor may give you either metronidazole (met-roh-NIH-duh-zohl) or clindamycin (klin-duh-MY-sin). Generally, male sex partners of women with BV don't need to be treated. However, BV can be spread to female partners. If your current partner is female, talk to her about treatment. You can get BV again even after being treated.

Is it safe to treat pregnant women who have BV?

All pregnant women with symptoms of BV should be tested and treated if they have it. This is especially important for pregnant women who have had a premature delivery or low birth weight baby in the past. There are treatments available at any stage of your pregnancy. Be sure to talk to your doctor about what is right for you.

Can BV cause health problems?

In most cases, BV doesn't cause any problems. But some problems can arise if BV is untreated.

- Pregnancy problems. BV can cause premature delivery and low birth weight babies (less than five pounds).

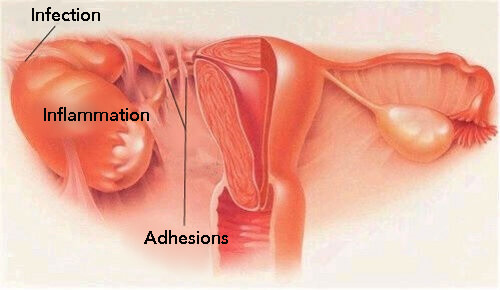

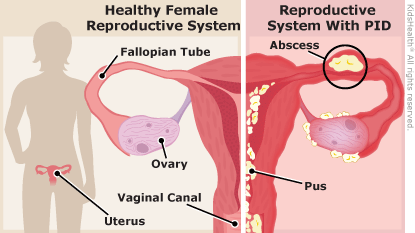

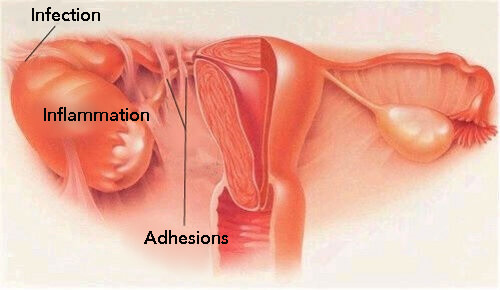

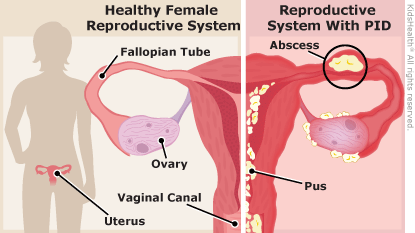

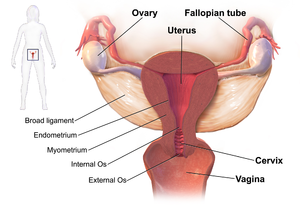

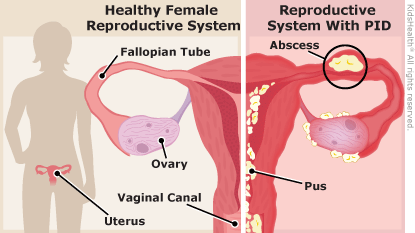

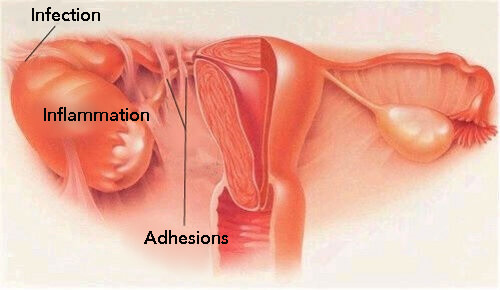

- PID. Pelvic inflammatory disease or PID is an infection that can affect a woman's uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. Having BV increases the risk of getting PID after a surgical procedure, such as a hysterectomy or an abortion.

- Higher risk of getting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Having BV can raise your risk of HIV, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. Women with HIV who get BV are also more likely to pass HIV to a sexual partner.

How can I lower my risk of BV?

Experts are still figuring out the best way to prevent BV. But there are steps you can take to lower your risk.

- Help keep your vaginal bacteria balanced. Wash your vagina and anus every day with mild soap. When you go to the bathroom, wipe from your vagina to your anus. Keep the area cool by wearing cotton or cotton-lined underpants. Avoid tight pants and skip the pantyhose in summer.

- Don't douche. Douching removes some of the normal bacteria in the vagina that protects you from infection. This may raise your risk of BV. It may also make it easier to get BV again after treatment.

- Have regular pelvic exams. Talk with your doctor about how often you need exams, as well as STI tests.

- Finish your medicine. If you have BV, finish all the medicine your doctor gives you to treat it. Even if the symptoms go away, you still need to finish all of the medicine.

Practicing safe sex is also very important. Below are ways to help protect yourself.

- Don't have sex. The best way to prevent any STI is to not have vaginal, oral, or anal sex.

- Be faithful. Having sex with just one partner can also lower your risk. Be faithful to each other. That means that you only have sex with each other and no one else.

- Use condoms. Protect yourself with a condom EVERY time you have vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Condoms should be used for any type of sex with every partner. For vaginal sex, use a latex male condom or a female polyurethane condom. For anal sex, use a latex male condom. For oral sex, use a condom or a dental dam. A dental dam is a rubbery material that can be placed over the anus or the vagina before sexual contact.

- Talk with your sex partner(s) about STIs and using condoms. It's up to you to make sure you are protected. Remember, it's YOUR body! For more information, call the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at 800-232-4636.

- Talk frankly with your doctor or nurse and your sex partner(s) about any STIs you or your partner(s) have or had. Talk about any discharge in the genital area. Try not to be embarrassed.

More information on bacterial vaginosis

For more information about bacterial vaginosis, call womenshealth.gov at 800-994-9662 (TDD: 888-220-5446) or contact the following organizations:

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Phone: 202-638-5577

- American Social Health Association

Phone: 919-361-8400

- Association of Reproductive Health Professionals

Phone: 202-466-3825

- CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN), CDC, HHS

Phone: 800-458-5231

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP), CDC, HHS

Phone: 800-232-4636

- Healthy Women

Phone: 877-986-9472

Source: Office on Women's Health, HHS

Any woman can get bacterial vaginosis. Having bacterial vaginosis can increase your chance of getting an STD.

The content here can be syndicated (added to your web site).

Print Version

Commercial Print Version

What is bacterial vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is an infection caused when too much of certain bacteria change the normal balance of bacteria in the vagina.

How common is bacterial vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal infection in women ages 15-44.

How is bacterial vaginosis spread?

We do not know about the cause of BV or how some women get it. BV is linked to an imbalance of “good” and “harmful” bacteria that are normally found in a woman's vagina.

We do know that having a new sex partner or multiple sex partners and douching can upset the balance of bacteria in the vagina and put women at increased risk for getting BV.

However, we do not know how sex contributes to BV. BV is not considered an STD, but having BV can increase your chances of getting an STD. BV may also affect women who have never had sex.

You cannot get BV from toilet seats, bedding, or swimming pools.

How can I avoid getting bacterial vaginosis?

Doctors and scientists do not completely understand how BV is spread, and there are no known best ways to prevent it.

The following basic prevention steps may help lower your risk of developing BV:

- Not having sex;

- Limiting your number of sex partners; and

- Not douching.

STDs & Pregnancy

I’m pregnant. How does bacterial vaginosis affect my baby?

Pregnant women can get BV. Pregnant women with BV are more likely to have babies who are born premature (early) or with low birth weight than women who do not have BV while pregnant. Low birth weight means having a baby that weighs less than 5.5 pounds at birth.

Treatment is especially important for pregnant women.

How do I know if I have bacterial vaginosis?

Many women with BV do not have symptoms. If you do have symptoms, you may notice a thin white or gray vaginal discharge, odor, pain, itching, or burning in the vagina. Some women have a strong fish-like odor, especially after sex. You may also have burning when urinating; itching around the outside of the vagina, or both.

How will my doctor know if I have bacterial vaginosis?

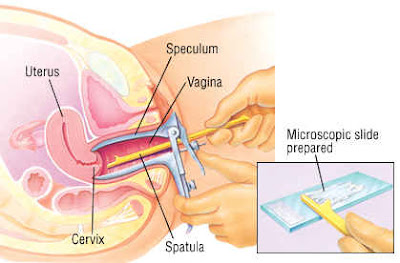

A health care provider will look at your vagina for signs of BV and perform laboratory tests on a sample of vaginal fluid to determine if BV is present.

Can bacterial vaginosis be cured?

BV will sometimes go away without treatment. But if you have symptoms of BV you should be checked and treated. It is important that you take all of the medicine prescribed to you, even if your symptoms go away. A health care provider can treat BV with antibiotics, but BV can recur even after treatment. Treatment may also reduce the risk for STDs.

Male sex partners of women diagnosed with BV generally do not need to be treated. However, BV may be transferred between female sex partners.

What happens if I don't get treated?

BV can cause some serious health risks, including

- Increasing your chance of getting HIV if you have sex with someone who is infected with HIV;

- If you are HIV positive, increasing your chance of passing HIV to your sex partner;

- Making it more likely that you will deliver your baby too early if you have BV while pregnant;

- Increasing your chance of getting other STDs, such as chlamydia and gonorrhea. These bacteria can sometimes cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can make it difficult or impossible for you to have children.

Where can I get more information?

Division of STD Prevention (DSTDP)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

www.cdc.gov/std

Order Publication Online at www.cdc.gov/std/pub

CDC-INFO Contact Center

1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348

Contact CDC-INFO

CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN)

P.O. Box 6003

Rockville, MD 20849-6003

E-mail: npin-info@cdc.gov

Sources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR 2010;59(No. RR-12)

Hillier S and Holmes K. Bacterial vaginosis. In: K. Holmes, P. Sparling, P. Mardh et al (eds). Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 3rd Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999, 563-586.

Related Content

- STDs & Pregnancy Fact Sheet

- Pregnancy and HIV, Viral Hepatitis, and STD Prevention

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Fact Sheet

Content provided and maintained by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Please see the system usage guidelines and disclaimer.

CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

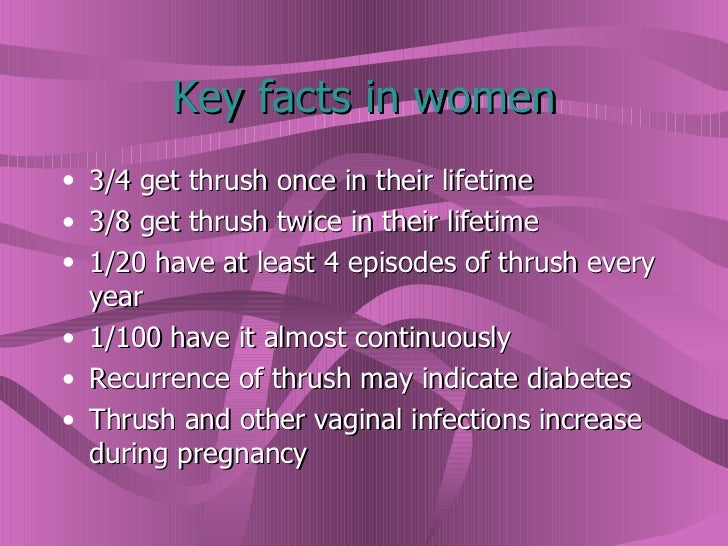

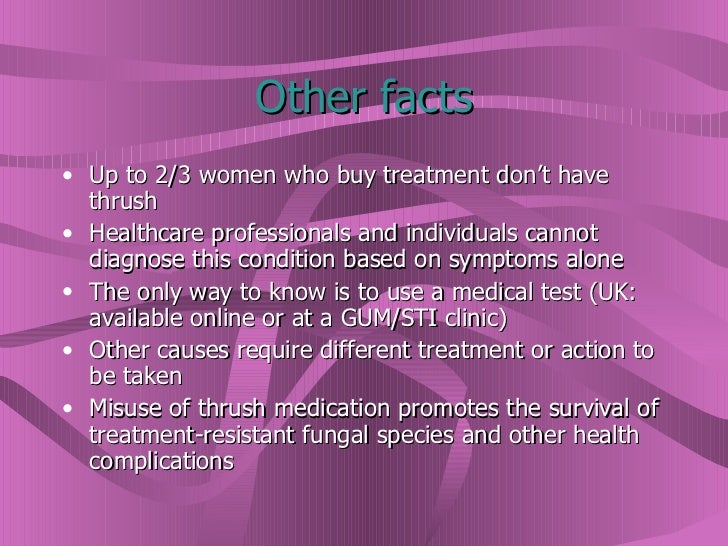

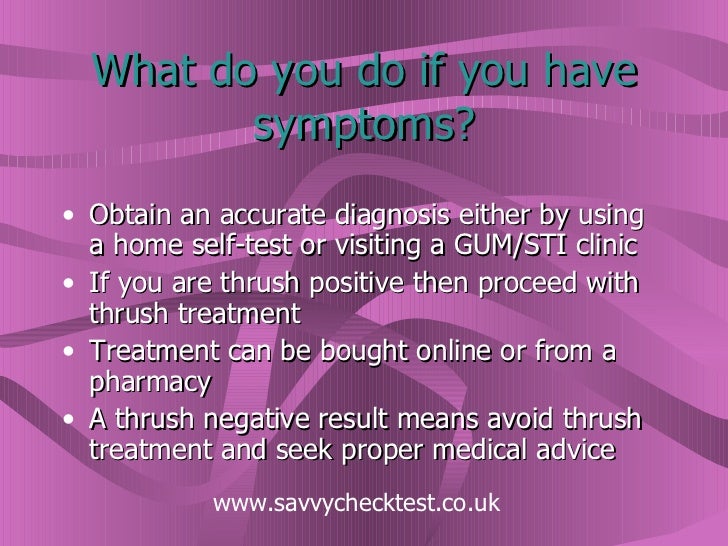

CONDITION: Candidiasis

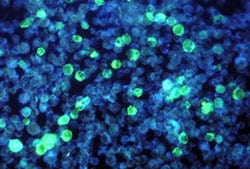

Photomicrograph of the fungus Candida albicans

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by yeasts that belong to the genus Candida. There are over 20 species of Candida yeasts that can cause infection in humans, the most common of which is Candida albicans. Candida yeasts normally reside in the intestinal tract and can be found on mucous membranes and skin without causing infection; however, overgrowth of these organisms can cause symptoms to develop. Symptoms of candidiasis vary depending on the area of the body that is infected.

Candidiasis that develops in the mouth or throat is called “thrush” or oropharyngeal candidiasis. Candidiasis in the vagina is commonly referred to as a “yeast infection.” Invasive candidiasis occurs when Candida species enter the bloodstream and spread throughout the body. Click the links below for more information on the different types of Candida infections.

For other fungal topics, visit the fungal diseases homepage.

Types of Candidiasis

- Oropharyngeal / Esophageal Candidiasis

- Genital / vulvovaginal candidiasis

- Invasive Candidiasis

Global Emergence of Candida auris

Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat. Healthcare facilities in several countries have reported that C. auris has caused severe illness in hospitalized patients. C. auris is often resistant to multiple antifungal drugs.

Source: CDC

Oral Candidiasis/mouth thrush

Oral candidiasis (kan-dih-DEYE-uh-suhss), or thrush, is a type of fungal infection inside the mouth. Thrush causes swelling and a thick white coating on your mouth, tongue, throat, and esophagus. (The infection is only called oral candidiasis if it appears in your mouth.) Thrush happens when candida, a fungus that is normally found in the body, grows too much in these areas. It also can overgrow in your vagina. This is called a vaginal yeast infection. Thrush is common in people living with HIV and can be hard to get rid of. Thrush is partly diagnosed by how your mouth looks. A doctor might also take a scraping of the white patches in your mouth that will appear with an infection. Thrush is usually first treated with prescription lozenges and mouth rinses. If this doesn't work or the thrush keeps coming back, antifungal drugs are used. If thrush is not treated, symptoms will last. In very rare cases, untreated thrush may enter the bloodstream and spread throughout the body.

Source: OWH, HHS

CONDITION: Chancroid

Chancroid is a bacterial infection that is spread through sexual contact.

Chancroid (caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, a bacteria):

Sexually Transmitted Disease Facts

NOTE: Chancroid is rare in the U.S. If you have signs or symptoms of any sexually transmitted disease you should see a health care provider for evaluation and possible treatment.

On this page:

Signs and Symptoms

Transmission

Complications

Prevention

Testing and Treatment

For More Information

Signs and Symptoms

Chancroid Symptoms:

- Painful and draining open sores in the genital area

- Painful, swollen lymph nodes in the groin

- Begin 4-10 days after exposure

Transmission

- Vaginal sex

- Oral sex

- Anal sex

- Skin to skin contact with infected lesion or sore

Complications

If left untreated, chancroid:

- Can spread to sex partners

- Makes it easier to transmit or acquire HIV during sex

- Can cause destruction of foreskin tissue on penis

- Sores can become infected with other germs

Prevention

- Avoiding vaginal, oral or anal sex is the best way to prevent STDs.

- Latex condoms, when used consistently and correctly, can reduce the risk of chancroid only when the infected areas are covered or protected by the condom.

- Always use latex condoms during vaginal and anal sex.

- Use a latex condom for oral sex on a penis.

- Use a latex barrier (dental dam or condom cut in half) for oral sex on a vagina or anus.

- Limit the number of sex partners.

- Notify sex partners immediately if infected.

- Infected sex partners should be tested and treated.

Testing and Treatment

- Get a test from a medical provider if infection is suspected.

- Chancroid can be cured using medication prescribed by a medical provider.

- Partners should be treated at the same time.

NOTE: A person can be re-infected after treatment.

For more information, contact:

STD, HIV and TB Section

Minnesota Department of Health

651-201-5414

Minnesota Family Planning and STD Hotline

1-800-783-2287 Voice/TTY; 651-645-9360 (Metro)

American Social Health Association (ASHA)

CDC National STD and AIDS Hotlines

1-800-CDC-INFO; 1-888-232-6348 TTY

1-800-344-7432 (Spanish)

Content Notice: This site contains HIV or STD prevention messages that may not be appropriate for all audiences. Since HIV and other STDs are spread primarily through sexual practices or by sharing needles, prevention messages and programs may address these topics. If you are not seeking such information or may be offended by such materials, please exit this web site.

Additional Information on Chancroid

The prevalence of chancroid has declined in the United States. When infection does occur, it is usually associated with sporadic outbreaks. Worldwide, chancroid appears to have declined as well, although infection might still occur in some regions of Africa and the Caribbean. Like genital herpes and syphilis, chancroid is a risk factor in the transmission and acquisition of HIV infection.

Diagnostic Considerations

A definitive diagnosis of chancroid requires the identification of H. ducreyi on special culture media that is not widely available from commercial sources; even when these media are used, sensitivity is <80%. No FDA-cleared PCR test for H. ducreyi is available in the United States, but such testing can be performed by clinical laboratories that have developed their own PCR test and have conducted CLIA verification studies in genital specimens.

The combination of a painful genital ulcer and tender suppurative inguinal adenopathy suggests the diagnosis of chancroid. For both clinical and surveillance purposes, a probable diagnosis of chancroid can be made if all of the following criteria are met: 1) the patient has one or more painful genital ulcers; 2) the clinical presentation, appearance of genital ulcers and, if present, regional lymphadenopathy are typical for chancroid; 3) the patient has no evidence of T. pallidum infection by darkfield examination of ulcer exudate or by a serologic test for syphilis performed at least 7 days after onset of ulcers; and 4) an HSV PCR test or HSV culture performed on the ulcer exudate is negative.

Treatment

Successful treatment for chancroid cures the infection, resolves the clinical symptoms, and prevents transmission to others. In advanced cases, scarring can result despite successful therapy.

Recommended Regimens

- Azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose

OR

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose

OR

- Ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice a day for 3 days

OR

- Erythromycin base 500 mg orally three times a day for 7 days

Azithromycin and ceftriaxone offer the advantage of single-dose therapy. Worldwide, several isolates with intermediate resistance to either ciprofloxacin or erythromycin have been reported. However, because cultures are not routinely performed, data are limited regarding the current prevalence of antimicrobial resistance.

Other Management Considerations

Men who are uncircumcised and patients with HIV infection do not respond as well to treatment as persons who are circumcised or HIV-negative. Patients should be tested for HIV infection at the time chancroid is diagnosed. If the initial test results were negative, a serologic test for syphilis and HIV infection should be performed 3 months after the diagnosis of chancroid.

Follow-Up

Patients should be re-examined 3–7 days after initiation of therapy. If treatment is successful, ulcers usually improve symptomatically within 3 days and objectively within 7 days after therapy. If no clinical improvement is evident, the clinician must consider whether 1) the diagnosis is correct, 2) the patient is coinfected with another STD, 3) the patient is infected with HIV, 4) the treatment was not used as instructed, or 5) the H. ducreyi strain causing the infection is resistant to the prescribed antimicrobial. The time required for complete healing depends on the size of the ulcer; large ulcers might require >2 weeks. In addition, healing is slower for some uncircumcised men who have ulcers under the foreskin. Clinical resolution of fluctuant lymphadenopathy is slower than that of ulcers and might require needle aspiration or incision and drainage, despite otherwise successful therapy. Although needle aspiration of buboes is a simpler procedure, incision and drainage might be preferred because of reduced need for subsequent drainage procedures.

Management of Sex Partners

Regardless of whether symptoms of the disease are present, sex partners of patients who have chancroid should be examined and treated if they had sexual contact with the patient during the 10 days preceding the patient’s onset of symptoms.

Special Considerations

Pregnancy

Data suggest ciprofloxacin presents a low risk to the fetus during pregnancy, with a potential for toxicity during breastfeeding. Alternate drugs should be used during pregnancy and lactation. No adverse effects of chancroid on pregnancy outcome have been reported.

HIV Infection

Persons with HIV infection who have chancroid should be monitored closely because they are more likely to experience treatment failure and to have ulcers that heal slowly. Persons with HIV infection might require repeated or longer courses of therapy, and treatment failures can occur with any regimen. Data are limited concerning the therapeutic efficacy of the recommended single-dose azithromycin and ceftriaxone regimens in persons with HIV infection.

CDC:Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

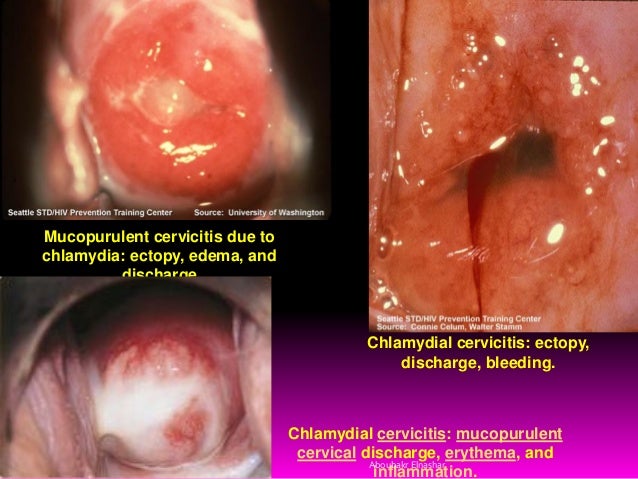

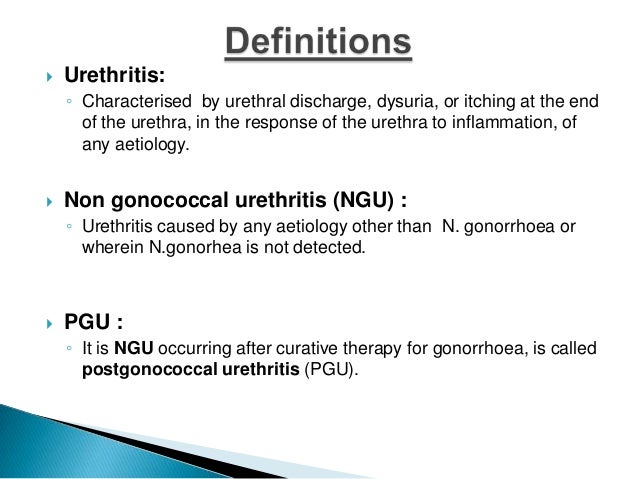

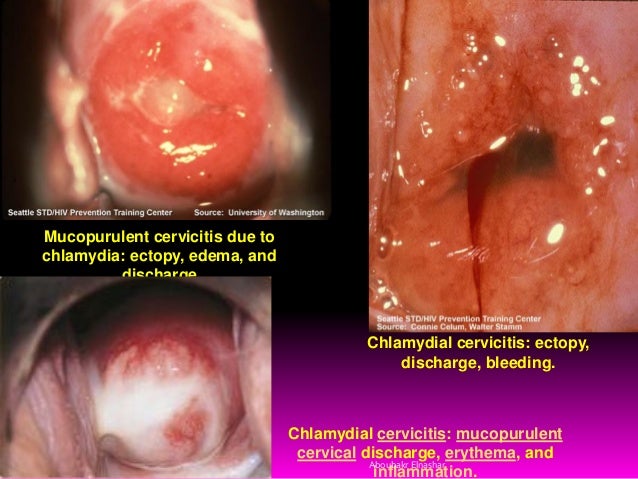

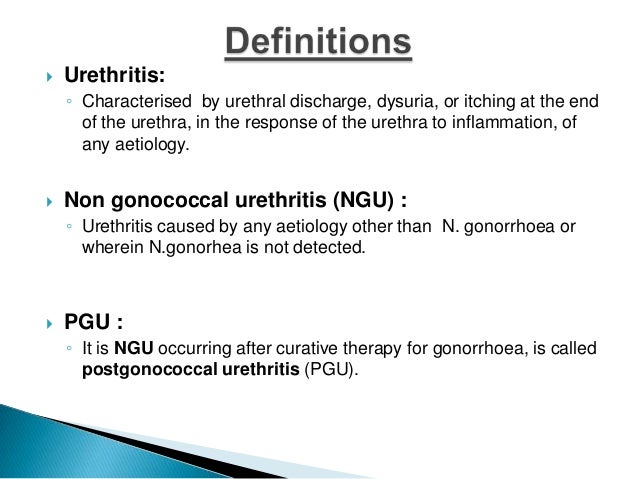

CONDITION: Chlamydia infection

- What is chlamydia and how common is it?

- How do you get chlamydia?

- What are the symptoms of chlamydia?

- How is chlamydia diagnosed?

- Who should get tested for chlamydia?

- What is the treatment for chlamydia?

- What should I do if I have chlamydia?

- What health problems can result from untreated chlamydia?

- How can chlamydia be prevented?

- More information on chlamydia

What is chlamydia and how common is it?

Chlamydia (kluh-MID-ee-uh) is a sexually transmitted infection (STI). STIs are also called STDs, or sexually transmitted diseases. Chlamydia is an STI caused by bacteria called chlamydia trachomatis. Chlamydia is the most commonly reported STI in the United States. Women, especially young women, are hit hardest by chlamydia.

Women often get chlamydia more than once, meaning they are "reinfected." This can happen if their sex partners were not treated. Reinfections place women at higher risk for serious reproductive health problems, such as infertility.

How do you get chlamydia?

You get chlamydia from vaginal, anal, or oral sex with an infected person. Chlamydia often has no symptoms. So people who are infected may pass chlamydia to their sex partners without knowing it. The more sex partners you (or your partner) have, the higher your risk of getting this STI.

An infected mother can pass chlamydia to her baby during childbirth. Babies born to infected mothers can get pneumonia (nuh-MOHN-yuh) or infections in their eyes.

What are the symptoms of chlamydia?

Chlamydia is known as a "silent" disease. This is because 75 percent of infected women and at least half of infected men have no symptoms.

If symptoms do occur, they most often appear within 1 to 3 weeks of exposure. The infection first attacks the cervix and urethra. Even if the infection spreads to the uterus and fallopian tubes, some women still have no symptoms. If you do have symptoms, you may have:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge

- Burning when passing urine

- Lower abdominal pain

- Low back pain

- Nausea

- Fever

- Pain during sex

- Bleeding between periods

Men with chlamydia may have:

- Discharge from the penis

- Burning when passing urine

- Burning and itching around the opening of the penis

- Pain and swelling in the testicles

The chlamydia bacteria also can infect your throat if you have oral sex with an infected partner.

Chlamydia is often not diagnosed or treated until problems show up. If you think you may have chlamydia, both you and your sex partner(s) should see a doctor right away — even if you have no symptoms.

Chlamydia can be confused with gonorrhea (gahn-uh-REE-uh), another STI. These STIs have some of the same symptoms and problems if not treated. But they have different treatments.

How is chlamydia diagnosed?

A doctor can diagnose chlamydia through:

- A swab test, where a fluid sample from an infected site (cervix or penis) is tested for the bacteria

- A urine test, where a urine sample is tested for the bacteria

A Pap test is not used to detect chlamydia.

Who should get tested for chlamydia?

You should be tested for chlamydia once a year if you are:

- 25 or younger and have sex

- Older than 25 and:Pregnant

- Have a new sex partner

- Have more than one sex partner

- Have sex with someone who has other sex partners

- Have had chlamydia or another STI in the past

- Have traded sex for money or drugs

- Do not use condoms during sex within a relationship that is not mutually monogamous, meaning you or your partner has sex with other people

You also should be tested if you have any symptoms of chlamydia.

What is the treatment for chlamydia?

Antibiotics are used to treat chlamydia. If treated, chlamydia can be cured.

All sex partners should be treated to keep from getting chlamydia again. Do not have sex until you and your sex partner(s) have ended treatment.

Tell your doctor if you are pregnant! Your doctor can give you an antibiotic that is commonly used during pregnancy.

What should I do if I have chlamydia?

Chlamydia is easy to treat. But you should be tested and treated right away to protect your reproductive health. If you have chlamydia:

- See a doctor right away. Women with chlamydia are 5 times more likely to get HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, from an infected partner.

- Follow your doctor's orders and finish all your antibiotics. Even if symptoms go away, you need to finish all the medicine.

- Don't engage in any sexual activity while being treated for chlamydia.

- Tell your sex partner(s) so they can be treated.

- See your doctor again if your symptoms don't go away within 1 to 2 weeks after finishing the medicine.

- See your doctor again within 3 to 4 months for another chlamydia test. This is most important if your sex partner was not treated or if you have a new sex partner.

Doctors, local health departments, and STI and family planning clinics have information about STIs. And they can all test you for chlamydia. Don't assume your doctor will test you for chlamydia when you have your Pap test. Take care of yourself by asking for a chlamydia test.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has free information and offers a list of clinics and doctors who provide treatment for STIs. Call CDC-INFO at 800-CDC-INFO (232-4636), TTY: 888-232-6348. You can call for information without leaving your name.

What health problems can result from untreated chlamydia?

Untreated chlamydia can damage a woman's reproductive organs and cause other health problems. Like the disease itself, the damage chlamydia causes is often "silent."

For women, untreated chlamydia may lead to:

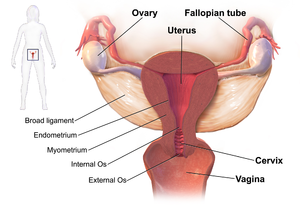

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID occurs when chlamydia bacteria infect the cells of the cervix, then spread to the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. PID occurs in up to 40 percent of women with untreated chlamydia. PID can lead to:Cystitis (siss-TEYE-tuhss), inflammation of the bladder.

- Infertility, meaning you can't get pregnant. The infection scars the fallopian tubes and keeps eggs from being fertilized.

- Ectopic or tubal pregnancy. This happens when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus. It is a medical emergency.

- Chronic pelvic pain, which is ongoing pain, most often from scar tissue.

-

- HIV/AIDS. Women who have chlamydia are 5 times more likely to get HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, from a partner who is infected with it.

For men, untreated chlamydia may lead to:

- Infection and scarring of the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the body

- Prostatitis (prah-stuh-TEYE-tuhss), swelling of the prostate gland

- Infection in the tube that carries sperm from the testes, causing pain and fever

- Infertility

For women and men, untreated chlamydia may lead to:

- Chlamydia bacteria in the throat, if you have oral sex with an infected partner

- Proctitis (prok-TEYE-tuhss), which is an infection of the lining of the rectum, if you have anal sex with an infected partner

- Reiter's syndrome, which causes arthritis, eye redness, and urinary tract problems

For pregnant women, chlamydia infections may lead to premature delivery. And babies born to infected mothers can get:

- Infections in their eyes, called conjunctivitis (kuhn-junk-tih-VEYE-tuhss) or pinkeye. Symptoms include discharge from the eyes and swollen eyelids. The symptoms most often show up within the first 10 days of life. If left untreated, it can lead to blindness.

- Pneumonia. Symptoms include congestion and a cough that keeps getting worse. Both symptoms most often show up within 3 to 6 weeks of birth.

Both of these infant health problems can be treated with antibiotics.

How can chlamydia be prevented?

You can take steps to lower your risk of getting chlamydia and other STIs. The following steps work best when used together. No single strategy can protect you from every type of STI.

- Don't have sex. The surest way to avoid getting chlamydia or any STI is to practice abstinence. This means not having vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

- Be faithful. Having sex with only one unaffected partner who only has sex with you will keep you safe from chlamydia and other STIs. Both parthers must be faithful all the time to avoid STI exposure. This means you have sex only with each other and no one else. The fewer sex partners you have, the lower your risk of being exposed to chlamydia and other STIs.

- Use condoms correctly and every time you have sex. Use condoms for all types of sexual contact, even if penetration does not take place. Condoms work by keeping blood, a man's semen, and a woman's vaginal fluid — all of which can carry chlamydia — from passing from one person to another. Use protection from the very beginning to the very end of each sex act, and with every sex partner. And be prepared: Don't rely on your partner to have protection.

- Know that most methods of birth control — and other methods — will not protect you from chlamydia and other STIs. Birth control methods including the pill, shots, implants, intrauterine devices (IUDs), diaphragms, and spermicides will not protect you from STIs. If you use one of these birth control methods, make sure to also use a condom with every sex act. You might have heard of other ways to keep from getting STIs — such as washing genitals before sex, passing urine after sex, douching after sex, or washing the genital area with vinegar after sex. These methods do not prevent the spread of STIs.

- Talk with your sex partner(s) about STIs and using condoms before having sex. Make it clear that you will not have any type of sex at any time without a condom. It's up to you to make sure you are protected. Remember, it's your body! For more information, call the CDC at 800-232-4636.

- Get tested for STIs. If either you or your partner has had other sexual partners in the past, get tested for STIs before becoming sexually active. This includes women who have sex with women. Most women who have sex with women have had sex with men, too. So a woman can get an STI, including chlamydia, from a male partner, and then pass it to a female partner. Don't wait for your doctor to ask you about getting tested — ask your doctor! Many tests for STIs can be done at the same time as your regular pelvic exam.

- Learn the symptoms of chlamydia. But remember, chlamydia often has no symptoms. Seek medical help right away if you think you may have chlamydia or another STI.

- Have regular checkups and pelvic exams — even if you think you're healthy. During the checkup, your doctor will ask you a lot of questions about your lifestyle, including your sex life. This might seem too personal to share. But answering honestly is the only way your doctor is sure to give you the care you need.

More information on chlamydia

For more information about chlamydia, call womenshealth.gov at 800-994-9662 (TDD: 888-220-5446) or contact the following organizations:

- CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN), CDC, HHS

Phone: 800-458-5231

- Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

Phone: 800-232-4636

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, HHS

Phone: 866- 284-4107, or 301-496-5717 (TDD: 800-877-8339)

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

Phone: 800-230-PLAN

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs), CDC, HHS

Phone: 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636)

Source: Office on Women's Health, HHS

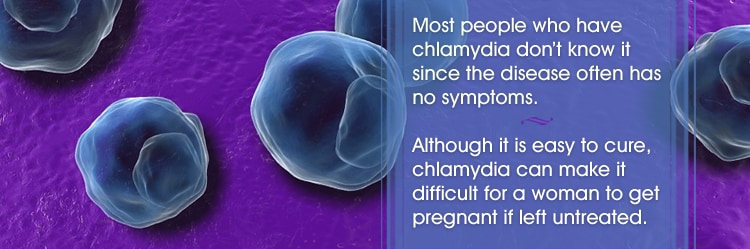

Chlamydia is a common sexually transmitted disease (STD) that can be easily cured. If left untreated, chlamydia can make it difficult for a woman to get pregnant.

What is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is a common STD that can infect both men and women. It can cause serious, permanent damage to a woman's reproductive system, making it difficult or impossible for her to get pregnant later on. Chlamydia can also cause a potentially fatal ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy that occurs outside the womb).

How is chlamydia spread?

You can get chlamydia by having vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone who has chlamydia.

If your sex partner is male you can still get chlamydia even if he does not ejaculate (cum).

If you’ve had chlamydia and were treated in the past, you can still get infected again if you have unprotected sex with someone who has chlamydia.

If you are pregnant, you can give chlamydia to your baby during childbirth.

How can I reduce my risk of getting chlamydia?

The only way to avoid STDs is to not have vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

If you are sexually active, you can do the following things to lower your chances of getting chlamydia:

- Being in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and has negative STD test results;

- Using latex condoms the right way every time you have sex.

Am I at risk for chlamydia?

Anyone who has sex can get chlamydia through unprotected vaginal, anal, or oral sex. However, sexually active young people are at a higher risk of getting chlamydia. This is due to behaviors and biological factors common among young people. Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men are also at risk since chlamydia can be spread through oral and anal sex.

Have an honest and open talk with your health care provider and ask whether you should be tested for chlamydia or other STDs. If you are a sexually active woman younger than 25 years, or an older woman with risk factors such as new or multiple sex partners, or a sex partner who has a sexually transmitted infection, you should get a test for chlamydia every year. Gay, bisexual, and men who have sex with men; as well as pregnant women should also be tested for chlamydia.

STDs & Pregnancy

I'm pregnant. How does chlamydia affect my baby?

If you are pregnant and have chlamydia, you can pass the infection to your baby during delivery. This could cause an eye infection or pneumonia in your newborn. Having chlamydia may also make it more likely to deliver your baby too early.

If you are pregnant, you should be tested for chlamydia at your first prenatal visit. Testing and treatment are the best ways to prevent health problems.

How do I know if I have chlamydia?

Most people who have chlamydia have no symptoms. If you do have symptoms, they may not appear until several weeks after you have sex with an infected partner. Even when chlamydia causes no symptoms, it can damage your reproductive system.

Women with symptoms may notice

- An abnormal vaginal discharge;

- A burning sensation when urinating.

Symptoms in men can include

- A discharge from their penis;

- A burning sensation when urinating;

- Pain and swelling in one or both testicles (although this is less common).

Men and women can also get infected with chlamydia in their rectum, either by having receptive anal sex, or by spread from another infected site (such as the vagina). While these infections often cause no symptoms, they can cause

- Rectal pain;

- Discharge;

- Bleeding.

You should be examined by your doctor if you notice any of these symptoms or if your partner has an STD or symptoms of an STD, such as an unusual sore, a smelly discharge, burning when urinating, or bleeding between periods.

How will my doctor know if I have chlamydia?

There are laboratory tests to diagnose chlamydia. Your health care provider may ask you to provide a urine sample or may use (or ask you to use) a cotton swab to get a sample from your vagina to test for chlamydia.

Can chlamydia be cured?

Yes, chlamydia can be cured with the right treatment. It is important that you take all of the medication your doctor prescribes to cure your infection. When taken properly it will stop the infection and could decrease your chances of having complications later on. Medication for chlamydia should not be shared with anyone.

Repeat infection with chlamydia is common. You should be tested again about three months after you are treated, even if your sex partner(s) was treated.

I was treated for chlamydia. When can I have sex again?

You should not have sex again until you and your sex partner(s) have completed treatment. If your doctor prescribes a single dose of medication, you should wait seven days after taking the medicine before having sex. If your doctor prescribes a medicine for you to take for seven days, you should wait until you have taken all of the doses before having sex.

STDs & Infertility

What happens if I don't get treated?

The initial damage that chlamydia causes often goes unnoticed. However, chlamydia can lead to serious health problems.

If you are a woman, untreated chlamydia can spread to your uterus and fallopian tubes (tubes that carry fertilized eggs from the ovaries to the uterus), causing pelvic inflammatory disease(PID). PID often has no symptoms, however some women may have abdominal and pelvic pain. Even if it doesn’t cause symptoms initially, PID can cause permanent damage to your reproductive system and lead to long-term pelvic pain, inability to get pregnant, and potentially deadly ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy outside the uterus).

Men rarely have health problems linked to chlamydia. Infection sometimes spreads to the tube that carries sperm from the testicles, causing pain and fever. Rarely, chlamydia can prevent a man from being able to have children.

Untreated chlamydia may also increase your chances of getting or giving HIV – the virus that causes AIDS.

Where can I get more information?

Division of STD Prevention (DSTDP)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

www.cdc.gov/std

CDC-INFO Contact Center

1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348

Contact CDC-INFO

CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN)

P.O. Box 6003

Rockville, MD 20849-6003

E-mail: npin-info@cdc.gov

American Sexual Health Association (ASHA)

P.O. Box 13827

Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-3827

1-800-783-9877

Related Content

- STDs & Infertility

- STDs & Pregnancy – CDC fact sheet

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) – CDC fact sheet

- Gonorrhea – CDC fact sheet

Content provided and maintained by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Please see the system usage guidelines and disclaimer.

Source: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, HHS

CONDITION: Congenital Syphilis

CDC Expert Commentary

Sarah Kidd, MD, MPH: “We are calling on clinicians to get back to the basics of syphilis prevention for pregnant women.”

Read More

What is congenital syphilis (CS)?

Congenital syphilis (CS) is a disease that occurs when a mother with syphilis passes the infection on to her baby during pregnancy. Learn more about syphilis.

How can CS affect my baby?

CS can have major health impacts on your baby. How CS affects your baby’s health depends on how long you had syphilis and if — or when — you got treatment for the infection.

CS can cause:

- Miscarriage (losing the baby during pregnancy),

- Stillbirth (a baby born dead),

- Prematurity (a baby born early),

- Low birth weight, or

- Death shortly after birth.

Darkfield micrograph of Treponema pallidum.

Up to 40% of babies born to women with untreated syphilis may be stillborn, or die from the infection as a newborn.

For babies born with CS, CS can cause:

- Deformed bones,

- Severe anemia (low blood count),

- Enlarged liver and spleen,

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes),

- Brain and nerve problems, like blindness or deafness,

- Meningitis, and

- Skin rashes.

Do all babies born with CS have signs or symptoms?

No. It is possible that a baby with CS won’t have any symptoms at birth. But without treatment, the baby may develop serious problems. Usually, these health problems develop in the first few weeks after birth, but they can also happen years later.

Babies who do not get treatment for CS and develop symptoms later on can die from the infection. They may also be developmentally delayed or have seizures.

How common is CS?

After a steady decline from 2008–2012, data show a sharp increase in CS rates. In 2015, the number of CS cases was the highest it’s been since 2001.

Public health professionals across the country are very concerned about the growing number of congenital syphilis cases in the United States. It is important to make sure you get tested for syphilis during your pregnancy.

I'm pregnant. Do I need to get tested for syphilis?

Yes. All pregnant women should be tested for syphilis at the first prenatal visit (the first time you see your doctor for health care during pregnancy). If you don’t get tested at your first visit, make sure to ask your doctor about getting tested during a future checkup. Some women should be tested more than once during pregnancy. Talk with your doctor about the number of syphilis cases in your area and your risk for syphilis to determine if you should be tested again at the beginning of the third trimester, and again when your baby is born.

Keep in mind that you can have syphilis and not know it. Many people with syphilis do not have any symptoms. Also, syphilis symptoms may be very mild, or be similar to signs of other health problems. The only way to know for sure if you have syphilis is to get tested.

Is there treatment for syphilis?

Yes. Syphilis can be treated and cured with antibiotics. If you test positive for syphilis during pregnancy, be sure to get treatment right away.

If you are diagnosed with and treated for syphilis, your doctor should do follow-up testing for at least one year to make sure that your treatment is working.

How will my doctor know if my baby has CS?

Your doctor must consider several factors to determine if your baby has CS. These factors will include the results of your syphilis blood test and, if you were diagnosed with syphilis, whether you received treatment for syphilis during your pregnancy. Your doctor may also want to test your baby’s blood, perform a physical exam of your baby, or do other tests, such as a spinal tap or an x-ray, to determine if your baby has CS.

CDC has specific recommendations for your healthcare provider on how to evaluate babies born to women who have positive syphilis tests during pregnancy.

My baby was born with CS. Is there a way to treat the infection?

Yes. There is treatment for CS. Babies who have CS need to be treated right away -- or they can develop serious health problems. Depending on the results of your baby’s medical evaluation, he/she may need antibiotics in a hospital for 10 days. In some cases, only one injection of antibiotic is needed.

It’s also important that babies treated for CS get follow-up care to make sure that the treatment worked.

How can I reduce the risk of my baby getting CS or having health problems associated with CS?

Your baby will not get CS if you do not have syphilis. There are two important things you can do to protect your baby from getting CS and the health problems associated with the infection:

- Get a syphilis test at your first prenatal visit.

- Reduce your risk of getting syphilis before and during your pregnancy.

Talk with your doctor about your risk for syphilis. Have an open and honest conversation about your sexual history and STD testing. Your doctor can give you the best advice on any testing and treatment that you may need.

Get a syphilis test at your first prenatal visit

If you are pregnant, and have syphilis, you can still reduce the risk of CS in your baby. Getting tested and treated for syphilis can prevent serious health complications in both mother and baby.

Prenatal care is essential to the overall health and wellness of you and your unborn child. The sooner you begin receiving medical care during pregnancy, the better the health outcomes will be for you and your unborn baby.

At your first prenatal visit, ask your doctor about getting tested for syphilis. It is important that you have an open and honest conversation with your doctor at this time. Discuss any new or unusual physical symptoms you may be experiencing, as well as any drugs/medicines you are using, and whether you have new or multiple sex partners. This information will allow your doctor to make the appropriate testing recommendations. Even if you have been tested for syphilis in the past, you should be tested again when you become pregnant.

If you test positive for syphilis, you will need to be treated right away. Do not wait for your next prenatal visit. It is also important that your sex partner(s) receive treatment. Having syphilis once does not protect you from getting it again. Even after you’ve been successfully treated, you can still be reinfected. For this reason you must continue to take actions that will reduce your risk of getting a new infection.

Reduce your risk of getting syphilis before and during your pregnancy

Preventing syphilis in women and their sex partners is the best way to prevent CS.

If you are sexually active, the following things can lower your chances of getting syphilis:

- Being in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested for syphilis and does not have syphilis.

- Using latex condoms the right way every time you have sex. Although condoms can prevent transmission of syphilis by preventing contact with a sore, you should know that sometimes syphilis sores occur in areas not covered by a condom, and contact with these sores can still transmit syphilis.

Also, talk with your doctor about your risk for syphilis. Have an open and honest conversation with your doctor about your sexual history and about STD testing. Your doctor can give you the best advice on any testing and treatment that you may need.

Remember that it’s possible to get syphilis and not know it, because sometimes the infection causes no symptoms, only very mild symptoms, or symptoms that mimic other illnesses.

Where can I get more information?

STD information and referrals to STD Clinics

CDC-INFO

1-800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636)

TTY: 1-888-232-6348

In English, en Español

Resources:

CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN)

P.O. Box 6003

Rockville, MD 20849-6003

E-mail: npin-info@cdc.gov

American Sexual Health Association (ASHA)

P. O. Box 13827

Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-3827

1-800-783-9877

Where can I get more information?

Syphilis and MSM – Fact Sheet

Congenital Syphilis – Fact Sheet

STDs during Pregnancy – Fact Sheet

STDs During Pregnancy Fact Sheet

More on Congenital Syphilis

Fig. 1 The syphilis bacterium, treponema pallidum attaching to a testicular cell. Source: The Encyclopedia Britannica, online.

Congenital syphilis

Congenital syphilis is a severe, disabling, and often life-threatening infection seen in infants. A pregnant mother who has syphilis can spread the disease through the placenta to the unborn infant.

Congenital syphilis is caused by the bacteria Treponema pallidum, which is passed from mother to child during fetal development or at birth. Nearly half of all children infected with syphilis while they are in the womb die shortly before or after birth.

Despite the fact that this disease can be cured with antibiotics if caught early, rising rates of syphilis among pregnant women in the United States have increased the number of infants born with congenital syphilis.

Symptoms in newborns may include:

- Failure to gain weight or failure to thrive

- Fever

- Irritability

- No bridge to nose (saddle nose)

- Rash of the mouth, genitals, and anus

- Rash: starting as small blisters on the palms and soles, and later changing to copper-colored, flat or bumpy rash on the face, palms, and soles

- Watery fluid from the nose

Symptoms in older infants and young children may include:

- Abnormal notched and peg-shaped teeth, called Hutchinson teeth

- Bone pain

- Blindness

- Clouding of the cornea

- Decreased hearing or deafness

- Gray, mucus-like patches on the anus and outer vagina

- Joint swelling

- Refusal to move a painful arm or leg

- Saber shins (bone problem of the lower leg)

- Scarring of the skin around the mouth, genitals, and anus

If the disorder is suspected at the time of birth, the placenta will be examined for signs of syphilis. A physical examination of the infant may show signs of liver and spleen swelling and bone inflammation.

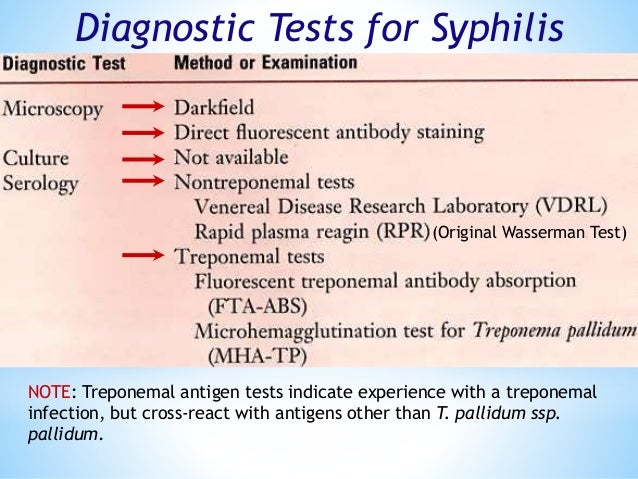

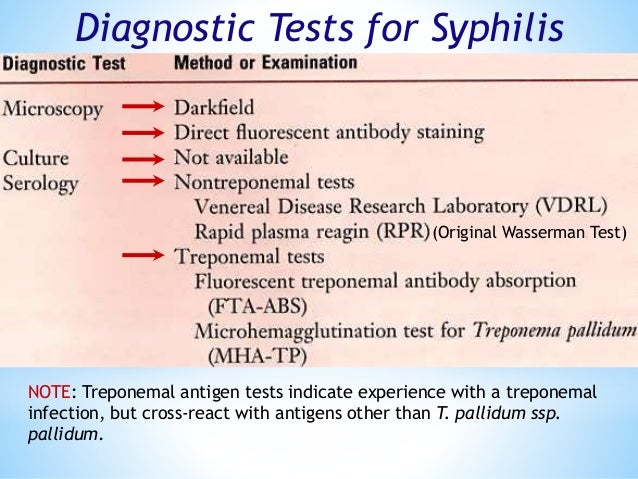

A routine blood test for syphilis is done during pregnancy. The mother may receive the following blood tests:

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed test (FTA-ABS)

- Rapid plasma reagin (RPR)

- Venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL)

An infant or child may have the following tests:

- Bone x-ray

- Dark-field examination to detect syphilis bacteria under a microscope

- Eye examination

- Lumbar puncture

Many infants who were infected early in the pregnancy are stillborn. Treatment of the expectant mother lowers the risk of congenital syphilis in the infant. Babies who become infected when passing through the birth canal have a better outlook.

Health problems that can result if the baby isn't treated include:

- Blindness

- Deafness

- Deformity of the face

- Nervous system problems

Call your health care provider if your baby has signs or symptoms of this condition.

If you think that you may have syphilis and are pregnant (or plan to get pregnant), call your provider right away.

Safer sexual practices help prevent the spread of syphilis. If you suspect you have a sexually transmitted disease such as syphilis, seek medical attention right away to avoid complications like infecting your baby during pregnancy or birth.

Prenatal care is very important. A routine blood test for syphilis is done during pregnancy. This identifies infected mothers so they can treated to reduce the risks to the infant and themselves. Infants born to infected mothers who received proper penicillin treatment during pregnancy are at minimal risk for congenital syphilis.

Congenital lues; Fetal syphilis

Source: Medlineplus, NLM, NIH

CDC: Symptoms of Syphilis (Click images to view full size)

Darkfield micrograph of Treponema pallidum.

Primary stage syphilis sore (chancre) on the surface of a tongue.

Lesions of secondary syphilis.

Secondary stage syphilis sores (lesions) on the palms of the hands. Referred to as "palmar lesions."

Secondary stage syphilis sores (lesions) on the bottoms of the feet. Referred to as "plantar lesions."

Secondary syphilis rash on the back.WARNING: the images below depicts the symptoms of STDs and are intended for educational use only. Parental caution is advised.

Primary stage syphilis sore (chancre) inside the vaginal opening.

Source: CDC

CONDITION: Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium is a microscopic parasite that causes the diarrheal disease cryptosporidiosis. Both the parasite and the disease are commonly known as "Crypto."

There are many species of Cryptosporidium that infect animals, some of which also infect humans. The parasite is protected by an outer shell that allows it to survive outside the body for long periods of time and makes it very tolerant to chlorine disinfection.

While this parasite can be spread in several different ways, water (drinking water and recreational water) is the most common way to spread the parasite. Cryptosporidium is a leading cause of waterborne disease among humans in the United States.

CDC

Infectious Diseases Related to Travel

Cryptosporidiosis

Michele C. Hlavsa, Lihua Xiao

INFECTIOUS AGENT

Among the many protozoan parasites in the genus Cryptosporidium, Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum most frequently cause human infections.

TRANSMISSION

Cryptosporidium is transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Its low infectious dose, prolonged survival in moist environments, protracted communicability, and extreme chlorine tolerance make Cryptosporidium ideally suited for transmission through contaminated drinking or recreational water, such as swimming pools. Transmission can also occur through contaminated food, or contact with infected people, or contaminated surfaces.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cryptosporidiosis is endemic worldwide. Of 22 US Peace Corps volunteers, 9 developed anti-Cryptosporidium IgG while serving in Africa. International travel is a risk factor for sporadic cryptosporidiosis in the United States and other industrialized nations; however, few studies have assessed the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in travelers. One study found 2.9% prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection among those with travel-associated diarrhea; cryptosporidiosis was significantly associated with travel to Asia, particularly India, and Latin America. Another study found a 6.4% prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection among North Americans with diarrhea associated with travel to 2 Mexican cities. This study suggests an association between cryptosporidiosis and length of travel.

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

Symptoms begin within 2 weeks (typically 5–7 days) after infection and are generally self-limited. The most common symptom is watery diarrhea. Other symptoms can include urgency, tenesmus, abdominal cramps, flatulence, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, fever, decreased appetite, fatigue, joint pain, and headache. In immunocompetent people, symptoms typically resolve within 2–3 weeks; patients might experience a recurrence of symptoms after a brief period of recovery before complete symptom resolution. Clinical presentation of cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected patients varies with level of immunosuppression, ranging from no symptoms or transient disease to relapsing or chronic diarrhea or even choleralike diarrhea, which can lead to life-threatening wasting and malabsorption. Extraintestinal cryptosporidiosis (in the biliary or respiratory tract or rarely the pancreas) has been documented in children and immunocompromised people.

DIAGNOSIS

Tests for Cryptosporidium are typically not included in routine ova and parasite testing. Therefore, clinicians should specifically request testing for this parasite, when suspected. Because Cryptosporidium can be excreted intermittently, multiple stool collections (3 stool specimens collected on separate days) increase test sensitivity. Diagnostic techniques include direct fluorescent antibody (considered the gold standard), EIA testing, rapid immunochromatographic cartridge assays, and microscopy with modified acid-fast staining. False-positive results might occur when using rapid immunochromatographic cartridge assays if they are not used according to the manufacturer’s directions. Confirmation by microscopy might be considered.

TREATMENT

Most immunocompetent people will recover without treatment. Nitazoxanide is approved to treat cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent people aged ≥1 year. Nitazoxanide has not been shown to be an effective treatment of cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected patients. However, dramatic clinical and parasitologic responses have been reported in these patients after the immune system has been reconstituted with active combination antiretroviral therapy. Protease inhibitors might have direct anti-Cryptosporidium activity.

PREVENTION

Food and water precautions (see Chapter 2, Food & Water Precautions) and handwashing (www.cdc.gov/handwashing). Cryptosporidium is extremely tolerant to halogens (such as chlorine or iodine). Water can be treated effectively by heating it to a rolling boil for 1 minute or filtering with an absolute 1-µm filter. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are not effective against the parasite. Prevention recommendations can be found at www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/prevention-control.html.

CDC website: www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto

Source: CDC

CONDITION: Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus (pronounced sy-toe-MEG-a-low-vy-rus), or CMV, is a common virus that infects people of all ages. Over half of adults by age 40 have been infected with CMV. Once CMV is in a person’s body, it stays there for life and can reactivate. Most people infected with CMV show no signs or symptoms. However, CMV infection can cause serious health problems for people with weakened immune systems, as well as babies infected with the virus before they are born (congenital CMV).

About CMV

Cytomegalovirus (pronounced sy-toe-MEG-a-low-vy-rus), or CMV, is a common virus that infects people of all ages. In the United States, nearly one in three children are already infected with CMV by age 5 years. Over half of adults by age 40 have been infected with CMV. Once CMV is in a person's body, it stays there for life and can reactivate. A person can also be reinfected with a different strain (variety) of the virus.

Most people infected with CMV show no signs or symptoms. That’s because a healthy person's immune system usually keeps the virus from causing illness. However, CMV infection can cause serious health problems for people with weakened immune systems, as well as babies infected with the virus before they are born (congenital CMV).

Signs & Symptoms

Most people with CMV infection have no symptoms and aren’t aware that they have been infected. In some cases, infection in healthy people can cause mild illness that may include

- Fever,

- Sore throat,

- Fatigue, and

- Swollen glands.

Occasionally, CMV can cause mononucleosis or hepatitis (liver problem).

People with weakened immune systems who get CMV can have more serious symptoms affecting the eyes, lungs, liver, esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Babies born with CMV can have brain, liver, spleen, lung, and growth problems. Hearing loss is the most common health problem in babies born with congenital CMV infection, which may be detected soon after birth or may develop later in childhood.

Transmission and Prevention

People with CMV may shed (pass) the virus in body fluids, such as urine, saliva, blood, tears, semen, and breast milk. CMV is spread from an infected person in the following ways:

- From direct contact with urine or saliva, especially from babies and young children

- Through sexual contact

- From breast milk

- Through transplanted organs and blood transfusions

- From mother to child during pregnancy (congenital CMV)

Regular hand washing, particularly after changing diapers, is a commonly recommended step to decrease the spread of infections, and may reduce exposures to CMV.

Healthcare providers should follow standard precautions. For more recommendations in healthcare settings, see the Guide to Infection Prevention for Outpatient Settings.

Diagnosis

Blood tests can be used to diagnose CMV infections in people who have symptoms.

Treatment

Healthy people who are infected with CMV usually do not require medical treatment.

Medications are available to treat CMV infection in people who have weakened immune systems and babies who show symptoms of congenital CMV infection.

Babies Born with CMV (Congenital CMV Infection)

When a baby is born with cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, it is called congenital CMV infection. About one out of every 150 babies are born with congenital CMV infection. However, only about one in five babies with congenital CMV infection will be sick from the virus or will have long-term health problems.

Transmission

Women can pass CMV to their baby during pregnancy. The virus in the woman’s blood can cross through the placenta and infect the baby. This can happen when a pregnant woman experiences a first-time infection, a reinfection with a different CMV strain (variety), or a reactivation of a previous infection during pregnancy.

Signs & Symptoms

Most babies with congenital CMV infection never show signs or have health problems. However, some babies may have health problems that are apparent at birth or may develop later during infancy or childhood. Although not fully understood, it is possible for CMV to cause the death of a baby during pregnancy (pregnancy loss).

Some babies may have signs of congenital CMV infection at birth. These signs include

- Premature birth,

- Liver, lung and spleen problems,

- Small size at birth,

- Small head size, and

- Seizures.

Some babies with signs of congenital CMV infection at birth may have long-term health problems, such as

- Hearing loss,

- Vision loss,

- Intellectual disability[2 pages],

- Small head size,

- Lack of coordination,

- Weakness or problems using muscles, and

- Seizures.

Some babies without signs of congenital CMV infection at birth may have hearing loss. Hearing loss may be present at birth or may develop later in babies who passed their newborn hearing test.

Diagnosis

Congenital CMV infection can be diagnosed by testing a newborn baby’s saliva, urine, or blood. Such specimens must be collected for testing within two to three weeks after the baby is born in order to confirm a diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

Treatment and Management

Medicines, called antivirals, may decrease the risk of health problems and hearing loss in some infected babies who show signs of congenital CMV infection at birth.

Use of antivirals for treating babies with congenital CMV infection who have no signs at birth is not currently recommended.

Babies with congenital CMV infection, with or without signs at birth, should have regular hearing checks.

Regularly follow-up with your baby’s doctor to discuss the care and additional services your child may need.

Health Professionals & Clinical Overview

For most healthy people who acquire cytomegalovirus (CMV) after birth, there are few symptoms and no long-term health consequences. Some people who acquire CMV infection may experience a mononucleosis-like syndrome with prolonged fever and hepatitis. Once a person becomes infected, the virus establishes lifelong latency and may reactivate intermittently. Disease from reactivation of CMV infection rarely occurs unless the person's immune system is suppressed due to therapeutic drugs or disease.

For most people, CMV infection is not a serious health problem. However, certain groups are at high risk for serious complications from CMV infection:

- Infants infected in utero (congenital CMV infection)

- Very low birth weight and premature infants

- People with compromised immune systems, such as from organ and bone marrow transplants, and people infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Characteristics of the Virus

CMV is a herpesvirus. This group of viruses include herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus, and Epstein-Barr virus. These viruses share a characteristic ability to establish lifelong latency. After initial infection, which may cause few symptoms, CMV becomes latent, residing in cells without causing detectable damage or clinical illness.

People who are infected with CMV sometimes shed the virus in body fluids, such as urine, saliva, blood, tears, semen, and breast milk. The shedding of virus may occur intermittently, without any detectable signs, and without causing symptoms. However, in people who are severely immunocompromised by medication or disease, viral reactivation may lead to symptomatic disease.

Transmission

CMV is transmitted by direct contact with infectious body fluids, such as urine or saliva. CMV can be transmitted sexually and through transplanted organs and blood transfusions.

CMV can be transmitted to infants through contact with maternal genital secretions during delivery or through breast milk. Healthy infants and children who acquire CMV after birth generally have few, if any, symptoms or complications from the infection. Women who are infected with CMV can still breastfeed infants born full-term.

Although the virus is not highly contagious, it has been shown to spread among household members and young children in daycare centers.

Risk of CMV Infection

CMV infects people of all ages. In the United States; nearly one in three children are already infected with CMV by age 5 years. By 40 years, over half of adults have been infected with CMV.

Childcare workers

People who care for or work closely with young children may be at greater risk of CMV infection than other people because CMV infection is common among young children. By age 5 years, one in three children have been infected with CMV, usually from breastfeeding or contact with other young children. Although young children with CMV infection generally have no symptoms, CMV can be present in their body fluids for months after they first become infected. Regular hand washing, especially after contact with body fluids of young children, is commonly recommended to avoid spread of infections, including CMV.

Pregnant women

In the United States, nearly half of women have already been infected with CMV before their first pregnancy. Of women who have never had a CMV infection, it is estimated that 1-4% of them will have a primary infection during pregnancy.

A woman who has a primary CMV infection during pregnancy is more likely to pass CMV to her fetus than a women who is reinfected or has a reactivation of the latent virus during pregnancy. However, in the United States, 50-75% of congenital CMV infections occur among infants born to mothers already infected with CMV, who either had a reinfection or a reactivation during pregnancy.

Routine screening for primary CMV infection during pregnancy is not recommended in the United States. Most laboratory tests currently available cannot conclusively detect if a primary CMV infection occurred during pregnancy. This makes it difficult to counsel pregnant women about the risk to their fetuses. The lack of a proven treatment to prevent or treat infection of the fetus reduces the potential benefits of prenatal screening.

Very low birth weight and premature infants

There are no recommendations against breastfeeding by mothers who are CMV-seropositive. However, premature infants (born

Diagnosing CMV

Primary CMV infections usually go unrecognized because most people are asymptomatic or do not have specific symptoms. Primary CMV infection should be suspected if a woman

- Has symptoms of infectious mononucleosis but has negative test results for Epstein-Barr virus, or

- Shows signs of hepatitis, but has negative test results for hepatitis A, B, and C.

CMV may be detected by viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of infected blood, urine, saliva, cervical secretions, or breast milk.

CMV infection is usually diagnosed using serologic testing. Serum samples collected one to three months apart can be used to diagnose primary infection. Seroconversion (1st sample IgG negative, 2nd sample IgG positive) is clear evidence for recent primary infection. However, diagnosis of CMV infection between birth and one year can be complicated by the presence of maternal CMV IgG. For more information, see Interpretation of Laboratory Tests.

Treatment and Management

- No treatment is currently indicated for CMV infection in healthy people.

- Antiviral treatment is used for people with compromised immune systems who have either sight-related or life-threatening illnesses due to CMV infection.

- For congenital CMV treatment options, see Congenital CMV Infection.

Prevention

Regular handwashing, especially after contact with body fluids of young children, is commonly recommended to avoid spread of infections, including CMV.

Healthcare providers should follow standard precautions.

Vaccines are still in the research and development stage.

Congenital CMV Infection

About one out of every 150 infants are born with congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. However, only about one in five infants with congenital CMV infection will have long-term health problems.

Transmission

A pregnant woman can pass CMV to her fetus following primary infection, reinfection with a different CMV strain, or reactivation of a previous infection during pregnancy. The risk of transmission is greatest in the third trimester whereas risk of complications to the infant is greatest if infection occurs during the first trimester. Risk of transmission for primary infection is 30-40% in the first and second trimesters, and 40–70% in the third trimester.

Signs & Symptoms

Most infants with congenital CMV infection never have health problems. About 10% of infants with congenital CMV infection will have health problems that are apparent at birth, which include

- Premature birth,

- Liver, lung and spleen problems,

- Low birth weight,

- Microcephaly, and

- Seizures.

About 40-60% of infants born with signs of congenital CMV infection at birth will have long-term health problems, such as

- Hearing loss.

- Vision loss.

- Intellectual disability,

- Microcephaly,

- Lack of coordination,

- Weakness or problems using muscles, and

- Seizures.

Some infants without signs of congenital CMV infection at birth may later have hearing loss, but do not appear to have other long-term health problems. Hearing loss may be present at birth or may develop later in infants who passed their newborn hearing test. About 10-20% of infants with congenital CMV infection who have no signs at birth will have, or later develop, hearing loss.

Diagnosing Congenital CMV Infection

Congenital CMV infection is diagnosed by detection of CMV in the urine, saliva, blood, or other tissues within two to three weeks after birth. Only tests that detect CMV live virus (through viral culture) or CMV DNA (through polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) can be used to diagnose congenital CMV infection. Congenital CMV infection cannot be diagnosed using samples collected more than two to three weeks after birth because testing after this time cannot distinguish between congenital infection and an infection acquired during and after delivery.

Serological tests are not recommended for diagnosing congenital CMV infection. Maternal IgG antibodies pass through the placenta during pregnancy; thus, CMV IgG testing of infants may reflect maternal antibody status, and does not necessarily indicate infection in the infant. Maternal IgM antibodies do not cross the placenta and, thus, CMV IgM in the newborn would indicate congenital infection, but is only present in 25-40% of newborns with congenital infection.

For diagnosis of acquired CMV infection see Interpretation of Laboratory Tests.

Treatment and Management

- Antiviral medications, such as ganciclovir or valganciclovir, may improve hearing and developmental outcomes in infants with symptoms of congenital CMV disease. Ganciclovir can have serious side effects, and has only been studied in infants with symptomatic congenital CMV disease. There is limited data on the effectiveness of ganciclovir or valganciclovir to treat infants with isolated hearing loss.

- Any infant diagnosed with congenital CMV infection should have his or her hearing and vision tested regularly. Most infants with congenital CMV grow up healthy. However, if the child has delayed onset of hearing or vision problems, early detection may improve outcomes. To learn more, see this CDC website about hearing loss in children.

Source: CDC

CONDITION: Donovanosis (Granuloma Inguinale)