Emergency contraception (morning after pill, IUD)

Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex or if your contraceptive method has failed – for example, a condom has split or you've missed a pill. There are two types:

- the emergency contraceptive pill (sometimes called the morning after pill)

- the IUD (intrauterine device, or coil)

- At a glance: emergency contraception

- The emergency pill

- The IUD as emergency contraception

- Where to get emergency contraception

- Contraception for the future

There are two kinds of emergency contraceptive pill. Levonelle has to be taken within 72 hours (three days) of sex, and ellaOne has to be taken within 120 hours (five days) of sex. Both pills work by preventing or delaying ovulation (release of an egg).

The IUD can be inserted into your uterus up to five days after unprotected sex, or up to five days after the earliest time you could have ovulated. It may stop an egg from being fertilised or implanting in your womb.

Emergency contraception does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

At a glance: facts about emergency contraception

- Both types of emergency contraception are effective at preventing pregnancy if they are used soon after unprotected sex. Less than 1% of women who use the IUD get pregnant, whereas pregnancies after the emergency contraceptive pill are not as rare. It’s thought that ellaOne is more effective than Levonelle.

- The sooner you take Levonelle or ellaOne, the more effective it will be.

- Levonelle or ellaOne can make you feel sick, dizzy or tired, or give you a headache, tender breasts or abdominal pain.

- Levonelle or ellaOne can make your period earlier or later than usual.

- If you’re sick (vomit) within two hours of taking Levonelle, or three hours of taking ellaOne, seek medical advice as you will need to take another dose or have an IUD fitted.

- If you use the IUD as emergency contraception, it can be left in as your regular contraceptive method.

- If you use the IUD as a regular method of contraception, it can make your periods longer, heavier or more painful.

- You may feel some discomfort when the IUD is put in – painkillers can help to relieve this.

- There are no serious side effects of using emergency contraception.

- Emergency contraception does not cause an abortion.

The emergency pill

How the emergency pill works

How effective the emergency pill is at preventing pregnancy

How it affects your period

Who can use the emergency pill

During pregnancy and breastfeeding

If you're already using the pill, patch, vaginal ring or injection

Side effects of the emergency pill

The emergency pill and other medicines

Can I get the emergency pill in advance?

How the emergency pill works

Levonelle

Levonelle contains levonorgestrel, a synthetic version of the natural hormone progesterone. In a woman’s body, progesterone plays a role in ovulation and preparing the uterus for accepting a fertilised egg.

It’s not known exactly how Levonelle works, but it’s thought to work primarily by preventing or delaying ovulation. You can take Levonelle more than once in a menstrual cycle. It does not interfere with your regular method of contraception.

ellaOne

ellaOne contains ulipristal acetate, which means that it stops progesterone working normally. It prevents pregnancy mainly by preventing or delaying ovulation. ellaOne may prevent other types of hormonal contraception from working for a week after use, and it’s not recommended for use more than once in a menstrual cycle.

ellaOne used to be available only on prescription, but it is now available to buy in some pharmacies.

Levonelle and ellaOne do not protect you against pregnancy during the rest of your menstrual cycle and are not intended to be a regular form of contraception. Using the emergency contraceptive pill repeatedly can disrupt your natural menstrual cycle.

How effective is the emergency pill at preventing pregnancy?

- most GP surgeries

- community contraception clinics

- some GUM clinics

- sexual health clinics

- some young people's services

Find a clinic near you

It can be difficult to know how many pregnancies the emergency pill prevents, because there is no way to know for sure how many women would have got pregnant if they did not take it.

A trial undertaken by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that levonorgestrel (the drug in Levonelle) prevented:

- 95% of expected pregnancies when taken within 24 hours of sex

- 85% if taken within 25-48 hours

- 58% if taken within 49-72 hours

More recent studies suggest that the prevention rate might be lower, but still substantial.

A study published in 2010 showed that of 1,696 women who received the emergency pill within 72 hours of sex, 37 became pregnant (1,659 did not). Of 203 women who took the emergency pill between 72 and 120 hours after unprotected sex, there were three pregnancies.

How it affects your period

After taking the emergency contraceptive pill, most women will have a normal period at the expected time. However, you may have your period later or earlier than normal.

If your period is more than seven days late, or is unusually light or short, contact your GP as soon as possible to check for pregnancy.

Who can use the emergency pill?

Most women can use the emergency contraceptive pill. This includes women who cannot usually use hormonal contraception, such as the combined pill and contraceptive patch.

Levonelle

The WHO does not identify any medical condition that would mean a woman shouldn’t use Levonelle.

ellaOne

The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) advises that ellaOne should not be used by women who:

- may already be pregnant

- are allergic to any of the components of the drug

- have severe asthma that is not properly controlled by steroids

- have hereditary problems with lactose metabolism

ellaOne will not be effective in women who are taking liver enzyme-inducing medication. For more information, read The emergency pill and other medicines.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Levonelle

There is no evidence that Levonelle harms a developing baby. It can be used even if there has been an earlier episode of unprotected sex in the menstrual cycle in addition to the current episode. Levonelle can be taken while breastfeeding. Although small amounts of the hormones contained in the pill may pass into your breast milk, it is not thought to be harmful to your baby.

ellaOne

There is limited information on the safety of ellaOne in pregnancy. The FSRH does not support the use of ellaOne if a woman might already be pregnant. The safety of ellaOne during breastfeeding is not yet known. The manufacturer recommends that you do not breastfeed for one week after taking this pill.

If you are already using the pill, patch, vaginal ring or contraceptive injection

If you need to take the emergency pill because you:

- forgot to take some of your regular contraceptive pills, or

- did not use your contraceptive patch or vaginal ring correctly, or

- were late having your contraceptive injection

then you should:

- take your next contraceptive pill, apply a new patch or insert a new ring within 12 hours of taking the emergency pill

You should then continue taking your regular contraceptive pill as normal.

If you have taken Levonelle, you will need to use additional contraception, such as condoms, for:

- the next seven days if you use the patch, ring, combined pill or injection

- the next two days if you use the progestogen-only pill

If you have taken ellaOne, you will need to use additional contraception, such as condoms, for:

- the next 14 days if you use the patch, ring, combined pill or injection

- the next nine days if you use the progestogen-only pill

What are the side effects of using the emergency pill?

Taking the emergency contraceptive pill has not been shown to cause any serious or long-term health problems. However, it can sometimes have side effects. Common side effects include:

- abdominal (tummy) pain

- headache

- irregular menstrual bleeding (spotting or heavy bleeding) before your next period is due

- feeling sick

- tiredness

Less common side effects include:

- breast tenderness

- dizziness

- headache

- vomiting (seek medical advice if you vomit within two hours of taking Levonelle, or three hours of taking ellaOne, as you will need to take another dose or have an IUD fitted)

If you are concerned about any symptoms after taking the emergency contraceptive pill, contact your GP or speak to a nurse at a sexual health clinic. You should talk to a doctor or nurse if:

- you think you might be pregnant

- your next period is more than seven days late

- your period is shorter or lighter than usual

- you have any sudden or unusual pain in your lower abdomen (this could be a sign of an ectopic pregnancy, where a fertilised egg implants outside the womb – this is rare but serious, and needs immediate medical attention)

The emergency pill and other medicines

The emergency contraceptive pill may interact with other medicines. These include:

- the herbal medicine St John’s Wort

- some medicines used to treat epilepsy

- some medicines used to treat HIV

- some medicines used to treat tuberculosis (TB)

- medication such as omeprazole (an antacid) to make your stomach less acidic

ellaOne cannot be used if you are already taking one of these medicines, as it may not be effective.

Levonelle may still be used, but the dose may need to be increased – your doctor or pharmacist can advise on this.

There should be no interaction between the emergency pill and most antibiotics. Two enzyme-inducing antibiotics (called rifampicin and rifabutin), used to treat or prevent meningitis or TB, may affect ellaOne while they’re being taken and for 28 days afterwards.

If you want to check that your medicines are safe to take with the emergency contraceptive pill, ask your GP or a pharmacist. You should also read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicines.

Can I get the emergency contraceptive pill in advance?

You may be able to get the emergency contraceptive pill in advance of having unprotected sex if:

- you are worried about your contraceptive method failing

- you are going on holiday

- you cannot get hold of emergency contraception easily

Ask your GP or nurse for further information on getting advance emergency contraception.

The IUD as emergency contraception

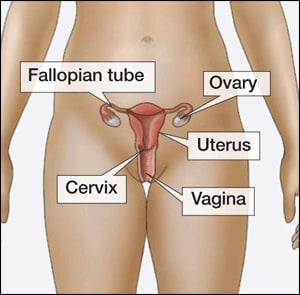

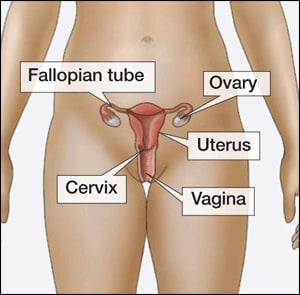

An intrauterine device (IUD)

- How the IUD works

- How effective the IUD is at preventing pregnancy

- Who can use the IUD

- During pregnancy and breastfeeding

- Side effects of using the IUD

- The IUD and other medicines

How the IUD works

The intrauterine device (IUD) is a small, T-shaped contraceptive device made from plastic and copper. It’s inserted into the uterus by a trained health professional. It may prevent an egg from implanting in your womb or being fertilised.

If you’ve had unprotected sex, the IUD can be inserted up to five days afterwards, to prevent pregnancy. It’s more effective at preventing pregnancy than the emergency pill, and it does not interact with any other medication.

You can also choose to have the IUD left in as an ongoing method of contraception.

How effective the IUD is at preventing pregnancy

There are several types of IUD. Newer ones have more copper and are more than 99% effective. Fewer than two women in 100 who use a newer IUD over five years will get pregnant. IUDs with less copper in them are less effective than this, but are still effective. The IUD is more effective than the emergency pill at preventing pregnancy after unprotected sex.

Who can use the IUD

Most women can use an IUD, including women who have never been pregnant and those who are HIV positive. Your GP or clinician will ask about your medical history to check if an IUD is suitable for you.

You should not use an IUD if you have:

- an untreated STI or a pelvic infection

- certain abnormalities of the womb or cervix

- any unexplained bleeding from your vagina – for example, between periods or after sex

Women who have had an ectopic pregnancy or recent abortion, or who have an artificial heart valve, must consult their GP or clinician before having an IUD fitted.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

The IUD should not be inserted if there is a risk that you may already be pregnant – for example, if you have had previous unprotected sex in the same menstrual cycle. The IUD can be used safely if you’re breastfeeding.

What are the side effects of the IUD

Complications after having an IUD fitted are rare, but can include pain, infection, damage to the womb or expulsion (the IUD coming out of your womb). If you use the IUD as an ongoing method of regular contraception, it may make your periods longer, heavier or more painful.

The IUD and other medicines

The emergency IUD will not react with any other medication.

Where can I get emergency contraception?

You can get the emergency contraceptive pill and the IUD for free from:

- a GP surgery that provides contraception (some GP surgeries may not provide the IUD)

- a contraception clinic

- a sexual health clinic (find sexual health services near you)

- some genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics

- some young people's clinics (call 0800 567123)

You can also get the emergency contraceptive pill free from:

- some pharmacies (find pharmacies near you)

- most NHS walk-in centres and minor injuries units

- some Accident & Emergency departments

The doctor or nurse you see may ask for the following information:

- when you have had unprotected sex in your current menstrual cycle

- the date of the first day of your last period and the usual length of your cycle

- details of any contraceptive failure (such as how many pills you may have missed, and when)

- if you've used any medications that may affect your contraception

You can buy the emergency contraceptive pill from most pharmacies if you're aged 16 or over (you need to be 18 or over to buy ellaOne) and from some organisations such as bpas or Marie Stopes. The cost varies, but it will be around £30.

Contraception for the future

If you're not using a regular method of contraception, you might consider doing so in order to lower the risk of unintended pregnancy. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) offers the most reliable protection against pregnancy, and you don't have to think about it every day or each time you have sex.

LARC methods are the:

- injection

- implant

- IUS

- IUD

The contraceptive injection

A woman can get pregnant if a man’s sperm reaches one of her eggs (ova). Contraception tries to stop this happening by keeping the egg and sperm apart or by stopping egg production. One method of contraception is the injection.

- At a glance: the contraceptive injection

- How it works

- Who can use it

- Advantages and disadvantages

- Risks

- Where you can get it

There are three types of contraceptive injections in the UK: Depo-Provera, which lasts for 12 weeks, Sayana Press, which lasts for 13 weeks, and Noristerat, which lasts for eight weeks. The most popular is Depo-Provera. Noristerat is usually used for only short periods of time – for example, if your partner is waiting for a vasectomy.

The injection contains progestogen. This thickens the mucus in the cervix, stopping sperm reaching an egg. It also thins the womb lining and, in some, prevents the release of an egg.

At a glance: the contraceptive injection

- If used correctly, the contraceptive injection is more than 99% effective. This means that less than one woman in 100 who use the injection will become pregnant in a year.

- The injection lasts for eight, 12 or 13 weeks (depending on the type), so you don't have to think about contraception every day or every time you have sex.

- It can be useful for women who might forget to take the contraceptive pill every day.

- It can be useful for women who can't use contraception that contains oestrogen.

- It's not affected by medication.

- The contraceptive injection may provide some protection against cancer of the womb and pelvic inflammatory disease.

- Side effects can include weight gain, headaches, mood swings, breast tenderness and irregular bleeding. The injection can't be removed from your body, so if you have side effects they'll last as long as the injection and for some time afterwards.

- Your periods may become more irregular or longer, or stop altogether (amenorrhoea). Treatment is available if your bleeding is heavy or longer than normal – talk to your doctor or nurse about this.

- It can take up to one year for your fertility to return to normal after the injection wears off, so it may not be suitable if you want to have a baby in the near future.

- Using Depo-Provera affects your natural oestrogen levels, which can cause thinning of the bones.

- The injection does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). By using condoms as well as the injection, you'll help to protect yourself against STIs.

How the injection works

- most GP surgeries

- community contraception clinics

- some GUM clinics

- sexual health clinics

- some young people's services

Find a clinic near you

The contraceptive injections Depo-Provera and Noristerat are usually given into a muscle in your bottom, although sometimes may be given in a muscle in your upper arm. Sayana Press is given under the skin (subcutaneously) rather than into a muscle, in the abdomen or thigh.

The contraceptive injection works in the same way as the implant. It steadily releases the hormone progestogen into your bloodstream. Progestogen is similar to the natural hormone progesterone, which is released by a woman's ovaries during her period.

The continuous release of progestogen:

- stops a woman releasing an egg every month (ovulation)

- thickens the mucus from the cervix (neck of the womb), making it difficult for sperm to pass through to the womb and reach an unfertilised egg

- makes the lining of the womb thinner, so that it is unable to support a fertilised egg

The injection can be given at any time during your menstrual cycle, as long as you and your doctor are reasonably sure you are not pregnant.

When it starts to work

If you have the injection during the first five days of your cycle, you will be immediately protected against becoming pregnant.

If you have the injection on any other day of your cycle, you will not be protected against pregnancy for up to seven days. Use condoms or another method of contraception during this time.

After giving birth

You can have the contraceptive injection at any time after you have given birth, if you are not breastfeeding. If you are breastfeeding, the injection will usually be given after six weeks, although it may be given earlier if necessary.

- If you start injections on or before day 21 after giving birth, you will be immediately protected against becoming pregnant.

- If you start injections after day 21, you will need to use additional contraception for the following seven days.

Heavy and irregular bleeding is more likely to occur if you have the contraceptive injection during the first few weeks after giving birth.

It is safe to use contraceptive injections while you are breastfeeding.

After a miscarriage or abortion

You can have the injection immediately after a miscarriage or abortion, and you will be protected against pregnancy straight away. If you have the injection more than five days after a miscarriage or abortion, you'll need to use additional contraception for seven days.

Who can use the injection?

Most women can be given the contraceptive injection. It may not be suitable if you:

- think you might be pregnant

- want to keep having regular periods

- have bleeding in between periods or after sex

- have arterial disease or a history of heart disease or stroke

- have a blood clot in a blood vessel (thrombosis)

- have liver disease

- have migraines

- have breast cancer or have had it in the past

- have diabetes with complications

- have cirrhosis or liver tumours

- are at risk of osteoporosis

Advantages and disadvantages of the injection

The main advantages of the contraceptive injection are:

- each injection lasts for either eight, 12 or 13 weeks

- the injection does not interrupt sex

- the injection is an option if you cannot use oestrogen-based contraception, such as the combined pill, contraceptive patch or vaginal ring

- you do not have to remember to take a pill every day

- the injection is safe to use while you are breastfeeding

- the injection is not affected by other medicines

- the injection may reduce heavy, painful periods and help with premenstrual symptoms for some women

- the injection offers some protection from pelvic inflammatory disease (the mucus from the cervix may stop bacteria entering the womb) and may also give some protection against cancer of the womb

Using the contraceptive injection may have some disadvantages, which you should consider carefully before deciding on the right method of contraception for you. These are as follows:

Disrupted periods

Your periods may change significantly during the first year of using the injection. They will usually become irregular and may be very heavy, or shorter and lighter, or stop altogether. This may settle down after the first year, but may continue as long as the injected progestogen remains in your body.

It can take a while for your periods and natural fertility to return after you stop using the injection. It takes around eight to 12 weeks for injected progestogen to leave the body, but you may have to wait longer for your periods to return to normal if you are trying to get pregnant.

Until you are ovulating regularly each month, it can be difficult to work out when you are at your most fertile. In some cases, it can take three months to a year for your periods to return to normal.

Weight gain

You may put on weight when you use the contraceptive injection, particulaly if you are under 18 years old and are overweight with a BMI (body mass index) of 30 or over.

Other side effects that some women report are:

- headaches

- acne

- tender breasts

- changes in mood

- loss of sex drive

Depo-Provera, oestrogen and bone risk

Using Depo-Provera affects your natural oestrogen levels, which can cause thinning of the bones, but it does not increase your risk of breaking a bone. This isn't a problem for most women, because the bone replaces itself when you stop the injection, and it doesn't appear to cause any long-term problems.

Thinning of the bones may be a problem for women who already have an increased risk of developing osteoporosis (for example, because they have low oestrogen, or a family history of osteoporosis). It may also be a concern for women under 18, because the body is still making bone at this age. Women under 18 may use Depo-Provera, but only after careful evaluation by a doctor.

Will other medicines affect the injection?

No – the contraceptive injection is not affected by other medication.

Risks

There is a small risk of infection at the site of the injection. In very rare cases, some people may have an allergic reaction to the injection.

Where you can get it

Most types of contraception are available free in the UK. Contraception is free to all women and men through the NHS. You can get contraception at:

- most GP surgeries – talk to your GP or practice nurse

- community contraception clinics

- some genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics

- sexual health clinics – they also offer contraceptive and STI testing services

- some young people’s services (call 0300 123 7123 for more information)

Find your nearest sexual health clinic by searching your postcode or town.

Contraception services are free and confidential, including for people under the age of 16.

If you're under 16 and want contraception, the doctor, nurse or pharmacist won't tell your parents (or carer) as long as they believe you fully understand the information you're given, and your decisions. Doctors and nurses work under strict guidelines when dealing with people under 16.

They'll encourage you to consider telling your parents, but they won't make you. The only time that a professional might want to tell someone else is if they believe you're at risk of harm, such as abuse. The risk would need to be serious, and they would usually discuss this with you first.

Find out more about the medicines used in the contraceptive injection.

Medicines for Contraceptive implants and injections

Over-the-counter medicine. Medicine with this icon can be bought without a prescription.

Over-the-counter medicine. Medicine with this icon can be bought without a prescription.

E-Etonogestrel-(a generic version of )

I-

N-

-Noristerat (a brand of )

Contraceptive Implant

A woman can get pregnant if a man’s sperm reaches one of her eggs (ova). Contraception tries to stop this happening by keeping the egg and sperm apart or by stopping egg production. One method is the implant.

- At a glance: facts about the contraceptive implant

- How it works

- Who can use it

- Advantages and disadvantages

- Risks

- Where you can get it

The contraceptive implant is a small flexible tube about 40mm long that's inserted under the skin of your upper arm. It's inserted by a trained professional, such as a doctor, and lasts for three years.

The implant stops the release of an egg from the ovary by slowly releasing progestogen into your body. Progestogen thickens the cervical mucus and thins the womb lining. This makes it harder for sperm to move through your cervix, and less likely for your womb to accept a fertilised egg.

At a glance: the implant

- If implanted correctly, it's more than 99% effective. Fewer than one woman in 1,000 who use the implant as contraception will get pregnant in one year.

- It's very useful for women who know they don't want to get pregnant for a while. Once the implant is in place, you don't have to think about contraception for three years.

- It can be useful for women who can't use contraception that contains oestrogen.

- It's very useful for women who find it difficult to take a pill at the same time every day.

- If you have side effects, the implant can be taken out. You can have the implant removed at any time, and your natural fertility will return very quickly.

- When it's first put in, you may feel some bruising, tenderness or swelling around the implant.

- In the first year after the implant is fitted, your periods may become irregular, lighter, heavier or longer. This usually settles down after the first year.

- A common side effect of the implant is that your periods stop (amenorrhoea). It's not harmful, but you may want to consider this before deciding to have an implant.

- Some medications can make the implant less effective, and additional contraceptive precautions need to be followed when you are taking these medications (see Will other medicines affect the implant?).

- The implant does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). By using condoms as well as the implant, you'll help to protect yourself against STIs.

How the implant works

The implant steadily releases the hormone progestogen into your bloodstream. Progestogen is similar to the natural hormone progesterone, which is released by a woman's ovaries during her period.

The continuous release of progestogen:

- stops a woman releasing an egg every month (ovulation)

- thickens the mucus from the cervix (entrance to the womb), making it difficult for sperm to pass through to the womb and reach an unfertilised egg

- makes the lining of the womb thinner so that it is unable to support a fertilised egg

- most GP surgeries

- community contraception clinics

- some GUM clinics

- sexual health clinics

- some young people's services

Find a clinic near you

The implant can be put in at any time during your menstrual cycle, as long as you and your doctor are reasonably sure you are not pregnant. In the UK, Nexplanon is the main contraceptive implant currently in use. Implants inserted before October 2010 were called Implanon. Since October 2010, insertion of Implanon has decreased as stocks are used up, and Nexplanon has become the most commonly used implant.

Both types of implant work in the same way, but Nexplanon is designed to reduce the risk of insertion errors and is visible on an X-ray or CT (computerised tomography) scan. There is no need for existing Implanon users to have their implant removed and replaced by Nexplanon ahead of its usual replacement time.

Nexplanon is a small, thin, flexible tube about 4cm long. It is implanted under the skin of your upper arm by a doctor or nurse. A local anaesthetic is used to numb the area. The small wound made in your arm is closed with a dressing and does not need stitches.

Nexplanon works for up to three years before it needs to be replaced. You can continue to use it until you reach the menopause, when a woman’s monthly periods stop (at around 52 years of age). The implant can be removed at any time by a specially trained doctor or nurse. It only takes a few minutes to remove, using a local anaesthetic.

As soon as the implant has been removed, you will no longer be protected against pregnancy.

When it starts to work

If the implant is fitted during the first five days of your menstrual cycle, you will be immediately protected against becoming pregnant. If it is fitted on any other day of your menstrual cycle, you will not be protected against pregnancy for up to seven days, and should use another method, such as condoms.

After giving birth

You can have the contraceptive implant fitted after you have given birth, usually after three weeks.

- If it is fitted on or before day 21 after the birth, you will be immediately protected against becoming pregnant.

- If it is fitted after day 21, you will need to use additional contraception, such as condoms, for the following seven days.

It is safe to use the implant while you are breastfeeding.

After a miscarriage or abortion

The implant can be fitted immediately after a miscarriage or an abortion, and you will be protected against pregnancy straight away.

Who can use the implant

Most women can be fitted with the contraceptive implant. It may not be suitable if you:

- think you might be pregnant

- want to keep having regular periods

- have bleeding in between periods or after sex

- have arterial disease or a history of heart disease or stroke

- have a blood clot in a blood vessel (thrombosis)

- have liver disease

- have migraines

- have breast cancer or have had it in the past

- have diabetes with complications

- have cirrhosis or liver tumours

- are at risk of osteoporosis

Advantages and disadvantages of the implant

The main advantages of the contraceptive implant are:

- it works for three years

- the implant does not interrupt sex

- it is an option if you cannot use oestrogen-based contraception, such as the combined contraceptive pill, contraceptive patch or vaginal ring

- you do not have to remember to take a pill every day

- the implant is safe to use while you are breastfeeding

- your fertility should return to normal as soon as the implant is removed

- implants offer some protection against pelvic inflammatory disease (the mucus from the cervix may stop bacteria entering the womb) and may also give some protection against cancer of the womb

- the implant may reduce heavy periods or painful periods after the first year of use

- after the contraceptive implant has been inserted, you should be able to carry out normal activities

Using a contraceptive implant may have some disadvantages, which you should consider carefully before deciding on the right method of contraception for you. These include:

Disrupted periods

Your periods may change significantly while using a contraceptive implant. Around 20% of women using the implant will have no bleeding, and almost 50% will have infrequent or prolonged bleeding. Bleeding patterns are likely to remain irregular, although they may settle down after the first year.

Although these changes are not harmful, they may not be acceptable for some women. Your GP may be able to help by providing additional medication if you have prolonged bleeding.

Other side effects that some women report are:

- headaches

- acne

- nausea

- breast tenderness

- changes in mood

- loss of sex drive

These side effects usually stop after the first few months. If you have prolonged or severe headaches or other side effects, tell your doctor.

Some women put on weight while using the implant, but there is no evidence to show that the implant causes weight gain.

Will other medicines affect the implant?

Some medicines can reduce the implant's effectiveness. These include:

- medication for HIV

- medication for epilepsy

- complementary remedies, such as St John's Wort

- an antibiotic called rifabutin (which can be used to treat tuberculosis)

- an antibiotic called rifampicin (which can be used to treat several conditions, including tuberculosis and meningitis)

These are called enzyme-inducing drugs. If you are using these medicines for a short while (for example, rifampicin to protect against meningitis), it is recommended that you use additional contraception during the course of treatment and for 28 days afterwards. The additional contraception could be condoms, or a single dose of the contraceptive injection. The implant can remain in place if you have the injection.

Women taking enzyme-inducing drugs in the long term may wish to consider using a method of contraception that isn't affected by their medication.

Always tell your doctor that you are using an implant if you are prescribed any medicines. Ask your doctor or nurse for more details about the implant and other medication.

Risks of the implant

In rare cases, the area of skin where the implant has been fitted can become infected. If this happens, the area will be cleaned and may be treated with antibiotics.

Where you can get the contraceptive implant

Most types of contraception are available for free in the UK. Contraception is free to all women and men through the NHS. Places where you can get contraception include:

- most GP surgeries – talk to your GP or practice nurse

- community contraception clinics

- some genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics

- sexual health clinics – they also offer contraceptive and STI testing services

- some young people’s services (call 0300 123 7123 for more information)

Find your nearest sexual health clinic by searching by postcode or town.

Contraception services are free and confidential, including for people under the age of 16.

If you're under 16 and want contraception, the doctor, nurse or pharmacist won't tell your parents (or carer) as long as they believe you fully understand the information you're given, and your decisions. Doctors and nurses work under strict guidelines when dealing with people under 16. They'll encourage you to consider telling your parents, but they won't make you. The only time that a professional might want to tell someone else is if they believe you're at risk of harm, such as abuse. The risk would need to be serious, and they would usually discuss this with you first.

Page last reviewed: 31/12/2014

Next review due: 31/12/2016

IUS (intrauterine system)

A woman can get pregnant if a man’s sperm reaches one of her eggs (ova). Contraception tries to stop this happening by keeping the egg and sperm apart or by stopping egg production. One method of contraception is the IUS, or intrauterine system (sometimes called the hormonal coil).

- At a glance: facts about the IUS

- How the IUS works

- Who can use the IUS

- Advantages and disadvantages of the IUS

- Risks of the IUS

- Where to get the IUS

An IUS is a small, T-shaped plastic device that is inserted into your womb (uterus) by a specially trained doctor or nurse.

The IUS releases a progestogen hormone into the womb. This thickens the mucus from your cervix, making it difficult for sperm to move through and reach an egg. It also thins the womb lining so that it's less likely to accept a fertilised egg. It may also stop ovulation (the release of an egg) in some women.

The IUS is a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method. It works for five years or three years, depending on the type, so you don't have to think about contraception every day or each time you have sex. Two brands of IUS are used in the UK – Mirena and Jaydess.

You can use an IUS whether or not you've had children.

At a glance: facts about the IUS

- It's more than 99% effective.Less than one in every 100 women who use Mirena will get pregnant in five years, and less than one in 100 who use Jaydess will get pregnant in three years.

- It can be taken out at any time by a specially trained doctor or nurse and your fertility quickly returns to normal.

- The IUS can make your periods lighter, shorter or stop altogether, so it may help women who have heavy periods or painful periods. Jaydess is less likely than Mirena to make your periods stop altogether.

- It can be used by women who can't use combined contraception (such as the combined pill) – for example, those who have migraines.

- Once the IUS is in place, you don't have to think about contraception every day or each time you have sex.

- Some women may experience mood swings, skin problems or breast tenderness.

- There's a small risk of getting an infection after it's inserted.

- It can be uncomfortable when the IUS is put in, although painkillers can help with this.

- The IUS can be fitted at any time during your monthly menstrual cycle, as long as you're definitely not pregnant. Ideally, it should be fitted within seven days of the start of your period, because this will protect against pregnancy straight away. You should use condoms for seven days if the IUS is fitted at any other time.

- The IUS does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). By using condoms as well as the IUS, you'll help to protect yourself against STIs.

How the IUS works

How it prevents pregnancy

Having an IUS fitted

How to tell whether an IUS is still in place

Removing an IUS

How it prevents pregnancy

The IUS is similar to the IUD (intrauterine device), but works in a slightly different way. Rather than releasing copper like the IUD, the IUS releases a progestogen hormone, which is similar to the natural hormone progesterone that's produced in a woman's ovaries.

Progestogen thickens the mucus from the cervix (opening of the womb), making it harder for sperm to move through it and reach an egg. It also causes the womb lining to become thinner and less likely to accept a fertilised egg. In some women, the IUS also stops the ovaries from releasing an egg (ovulation), but most women will continue to ovulate.

If you're 45 or older when you have the IUS fitted, it can be left until you reach menopause or you no longer need contraception.

Having an IUS fitted

- most GP surgeries

- community contraception clinics

- some GUM clinics

- sexual health clinics

- some young people's services

Find a clinic near you

An IUS can be fitted at any stage of your menstrual cycle, as long as you are not pregnant. If it's fitted in the first seven days of your cycle, you will be protected against pregnancy straight away. If it's fitted at any other time, you need to use another method of contraception (such as condoms) for seven days after it's fitted.

Before you have an IUS fitted, you will have an internal examination to determine the size and position of your womb. This is to make sure that the IUS can be positioned in the correct place.

You may also be tested for any existing infections, such as STIs. It is best to do this before an IUS is fitted so that any infections can be treated. You may be given antibiotics at the same time as an IUS is fitted.

It takes about 15 to 20 minutes to insert an IUS:

- the vagina is held open, like it is during a cervical screening (smear) test

- the IUS is inserted through the cervix and into the womb

The fitting process can be uncomfortable or painful for some women, and you may also experience cramps afterwards.

You can ask for a local anaesthetic or painkillers before having the IUS fitted. Discuss this with your GP or nurse beforehand. An anaesthetic injection itself can be painful, so many women have the procedure without one.

Once an IUS is fitted, it will need to be checked by a doctor after three to six weeks to make sure everything is fine. Speak to your GP or clinician if you have any problems after this initial check or if you want the IUS removed.

Also speak to your GP if you or your partner are at risk of getting an STI, as this can lead to infection in the pelvis.

See your GP or go back to the clinic if you:

- have pain in your lower abdomen

- have a high temperature

- have smelly discharge

This may mean you have an infection.

How to tell if an IUS is still in place

An IUS has two thin threads that hang down a little way from your womb into the top of your vagina. The GP or clinician that fits your IUS will teach you how to feel for these threads and check that the IUS is still in place.

Check your IUS is in place a few times in the first month and then after each period at regular intervals.

It is highly unlikely that your IUS will come out, but if you can't feel the threads or if you think the IUS has moved, you may not be fully protected against pregnancy. See your doctor or nurse straight away and use extra contraception, such as condoms, until your IUS has been checked. If you've had sex recently, you may need to use emergency contraception.

Your partner shouldn't be able to feel your IUS during sex. If he can feel the threads, get your GP or clinician to check that your IUS is in place. They may be able to cut the threads a little. If you feel any pain during sex, go for a check-up with your GP or clinician.

Removing an IUS

Your IUS can be removed at any time by a trained doctor or nurse.

If you're not going to have another IUS put in and you don't want to become pregnant, use another contraceptive method (such as condoms) for seven days before you have the IUS removed. Sperm can live for seven days in the body and could fertilise an egg once the IUS is removed. As soon as an IUS is taken out, your normal fertility should return.

Who can use an IUS

Most women can use an IUS, including women who have never been pregnant and those who are HIV positive. Your GP or clinician will ask about your medical history to check if an IUS is the most suitable form of contraception for you.

Your family and medical history will determine whether or not you can use an IUS. For example, this method of contraception may not be suitable for you if you have:

- breast cancer, or have had it in the past five years

- cervical cancer

- liver disease

- unexplained vaginal bleeding between periods or after sex

- arterial disease or history of serious heart disease or stroke

- an untreated STI or pelvic infection

- problems with your womb or cervix

An IUS may not be suitable for women who have untreated STIs. A doctor will usually give you a check-up to make sure you don't have any existing infections.

Using an IUS after giving birth

An IUS can usually be fitted four to six weeks after giving birth (vaginal or caesarean). You'll need to use alternative contraception from three weeks (21 days) after the birth until the IUS is put in. In some cases, an IUS can be fitted within 48 hours of giving birth. It is safe to use an IUS when you're breastfeeding, and it won't affect your milk supply.

Using an IUS after a miscarriage or abortion

An IUS can be fitted by an experienced doctor or nurse straight after an abortion or miscarriage, as long as you were pregnant for less than 24 weeks. If you were pregnant for more than 24 weeks, you may have to wait a few weeks before an IUS can be fitted.

Advantages and disadvantages of the IUS

Although an IUS is an effective method of contraception, there are several things to consider before having an IUS fitted.

Advantages of the IUS

- It works for five years (Mirena) or three years (Jaydess).

- It's one of the most effective forms of contraception available in the UK.

- It doesn't interrupt sex.

- An IUS may be useful if you have heavy or painful periods because your periods usually become much lighter and shorter, and sometimes less painful – they may stop completely after the first year of use.

- It can be used safely if you're breastfeeding.

- It's not affected by other medicines.

- It may be a good option if you can't take the hormone oestrogen, which is used in the combined contraceptive pill.

- Your fertility will return to normal when the IUS is removed.

There's no evidence that an IUS will affect your weight or that having an IUS fitted will increase the risk of cervical cancer, cancer of the uterus or ovarian cancer. Some women experience changes in mood and libido, but these changes are very small.

Disadvantages of the IUS

- Some women won't be happy with the way that their periods may change. For example, periods may become lighter and more irregular or, in some cases, stop completely. Your periods are more likely to stop completely with Mirena than with Jaydess.

- Irregular bleeding and spotting are common in the first six months after having an IUS fitted. This is not harmful and usually decreases with time.

- Some women experience headaches, acne and breast tenderness after having the IUS fitted.

- An uncommon side effect of the IUS is the appearance of small fluid-filled cysts on the ovaries – these usually disappear without treatment.

- An IUS doesn't protect you against STIs, so you may also have to use condoms when having sex. If you get an STI while you have an IUS fitted, it could lead to pelvic infection if it's not treated.

- Most women who stop using an IUS do so because of vaginal bleeding and pain, although this is uncommon. Hormonal problems can also occur, but these are even less common.

Risks of the IUS

Complications caused by an IUS are rare and usually happen in the first six months after it has been fitted. These include:

Damage to the womb

In rare cases (fewer than one in 1,000 insertions) an IUS can perforate (make a hole in) the womb or neck of the womb (cervix) when it is put in. This can cause pain in the lower abdomen, but doesn't usually cause any other symptoms. If the doctor or nurse fitting your IUS is experienced, the risk of perforation is extremely low.

If perforation occurs, you may need surgery to remove the IUS. Contact your GP straight away if you feel a lot of pain after having an IUS fitted. Perforations should be treated immediately.

Pelvic infections

Pelvic infections may occur in the first 20 days after the IUS has been inserted.

The risk of infection from an IUS is extremely small (fewer than one in 100 women who are at low risk of STIs will get an infection). A GP or clinician will usually recommend an internal examination before fitting an IUS to be sure that there are no existing infections.

Rejection

Occasionally, the IUS is rejected (expelled) by the womb or it can move (this is called displacement). This is not common and is more likely to happen soon after it has been fitted. Your doctor or nurse will teach you how to check that your IUS is in place.

Ectopic pregnancy

If the IUS fails and you become pregnant, your IUS should be removed as soon as possible if you are continuing with the pregnancy. There's a small increased risk of ectopic pregnancy if a woman becomes pregnant while using an IUS.

Where to get the IUS

Most types of contraception are available for free in the UK. Contraception is free to all women and men through the NHS. Places where you can get contraception include:

- most GP surgeries – talk to your GP or practice nurse

- community contraception clinics

- some genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics

- sexual health clinics – they also offer contraceptive and STI testing services

- some young people’s services (call 0300 123 7123 for more information)

Find sexual health services near you, including contraception clinics.

Contraception services are free and confidential, including for people under the age of 16.

If you're under 16 and want contraception, the doctor, nurse or pharmacist won't tell your parents or carer as long as they believe you fully understand the information you're given and your decisions. Doctors and nurses work under strict guidelines when dealing with people under 16.

They'll encourage you to consider telling your parents, but they won't make you. The only time that a professional might want to tell someone else is if they believe you're at risk of harm, such as abuse. The risk would need to be serious, and they would usually discuss this with you first.

IUD (intrauterine device)

A woman can get pregnant if a man’s sperm reaches one of her eggs (ova). Contraception tries to stop this by keeping the egg and sperm apart or by stopping eggs being produced. One method of contraception is the intrauterine device, or IUD (sometimes called a coil).

- At a glance: facts about the IUD

- How the IUD works

- Who can use the IUD

- Advantages and disadvantages of the IUD

- Risks of the IUD

- Where you can get an IUD

An IUD is a small T-shaped plastic and copper device that’s inserted into your womb (uterus) by a specially trained doctor or nurse.

The IUD works by stopping the sperm and egg from surviving in the womb or fallopian tubes. It may also prevent a fertilised egg from implanting in the womb.

The IUD is a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method. This means that once it's in place, you don't have to think about it each day or each time you have sex. There are several types and sizes of IUD.

You can use an IUD whether or not you've had children.

At a glance: facts about the IUD

- There are different types of IUD, some with more copper than others. IUDs with more copper are more than 99% effective. This means that fewer than one in 100 women who use an IUD will get pregnant in one year. IUDs with less copper will be less effective.

- An IUD works as soon as it's put in, and lasts for five to 10 years, depending on the type.

- It can be put in at any time during your menstrual cycle, as long as you're not pregnant.

- It can be removed at any time by a specially trained doctor or nurse and you'll quickly return to normal levels of fertility.

- Changes to your periods (for example, being heavier, longer or more painful) are common in the first three to six months after an IUD is put in, but they're likely to settle down after this. You might get spotting or bleeding between periods.

- There's a very small chance of infection within 20 days of the IUD being fitted.

- There's a risk that your body may expel the IUD.

- If you get pregnant, there's an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy (when the egg implants outside the womb). But because you're unlikely to get pregnant, the overall risk of ectopic pregnancy is lower than in women who don't use contraception.

- Having the IUD put in can be uncomfortable. Ask the doctor or nurse about pain relief.

- An IUD may not be suitable for you if you've had previous pelvic infections.

- The IUD does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). By using condoms as well as the IUD, you'll help to protect yourself against STIs.

How the IUD works

How it prevents pregnancy

Having an IUD fitted

How to tell whether an IUD is still in place

Removing an IUD

How it prevents pregnancy

The IUD is similar to the IUS (intrauterine system) but works in a different way. Instead of releasing the hormone progestogen like the IUS, the IUD releases copper. Copper changes the make-up of the fluids in the womb and fallopian tubes, stopping sperm surviving there. IUDs may also stop fertilised eggs from implanting in the womb.

There are types and sizes of IUD to suit different women. IUDs need to be fitted by a trained doctor or nurse at your GP surgery, local contraception clinic or sexual health clinic.

An IUD can stay in the womb for five to 10 years, depending on the type. If you're 40 or over when you have an IUD fitted, it can be left in until you reach the menopause or until you no longer need contraception.

Having an IUD fitted

An IUD can be fitted at any time during your menstrual cycle, as long as you are not pregnant. You'll be protected against pregnancy straight away.

Before you have an IUD fitted, you will have an internal examination to find out the size and position of your womb. This is to make sure that the IUD can be put in the correct place.

- most GP surgeries

- community contraception clinics

- some GUM clinics

- sexual health clinics

- some young people's services

Find a clinic near you

You may also be tested for infections, such as STIs. It's best to do this before an IUD is fitted so that you can have treatment (if you need it) before the IUD is put in. Sometimes, you may be given antibiotics at the same time as the IUD is fitted.

It takes about 15 to 20 minutes to insert an IUD. The vagina is held open, like it is during a cervical screening (smear) test, and the IUD is inserted through the cervix and into the womb.

The fitting process can be uncomfortable and sometimes painful. You may get cramps afterwards. You can ask for a local anaesthetic or painkillers before having the IUD fitted. An anaesthetic injection itself can be painful, so many women have the procedure without.

You may get pain and bleeding for a few days after having an IUD fitted. Discuss this with your GP or nurse beforehand.

The IUD needs to be checked by a doctor after three to six weeks. Speak to your doctor or nurse if you have any problems before or after this first check or if you want the IUD removed.

Speak to your doctor or nurse if you or your partner are at risk of getting an STI. This is because STIs can lead to an infection in the pelvis.

See your GP or go back to the clinic where your IUD was fitted as soon as you can if you:

- have pain in your lower abdomen

- have a high temperature

- have a smelly discharge

These may mean you have an infection.

How to tell whether an IUD is still in place

An IUD has two thin threads that hang down a little way from your womb into the top of your vagina. The doctor or nurse who fits your IUD will teach you how to feel for these threads and check that it is still in place.

Check your IUD is in place a few times in the first month, and then after each period or at regular intervals.

It's very unlikely that your IUD will come out, but if you can't feel the threads, or if you think the IUD has moved, you may not be fully protected against getting pregnant. See your doctor or nurse straight away and use an extra method of contraception, such as condoms, until your IUD has been checked. If you've had sex recently, you may need to use emergency contraception.

Your partner shouldn't be able to feel your IUD during sex. If he can feel the threads, get your doctor or nurse to check that your IUD is in place. They may be able to cut the threads to a shorter length. If you feel any pain during sex, go for a check-up.

Removing an IUD

An IUD can be removed at any time by a trained doctor or nurse.

If you're not going to have another IUD put in and you don't want to get pregnant, use another method (such as condoms) for seven days before you have the IUD removed. This is to stop sperm getting into your body. Sperm can live for up to seven days in the body and could make you pregnant once the IUD is removed.

As soon as an IUD is taken out, your normal fertility should return.

Who can use an IUD

Most women can use an IUD. This includes women who have never been pregnant and those who are HIV positive. Your doctor or nurse will ask about your medical history to check if an IUD is the most suitable form of contraception for you.

You should not use an IUD if you have:

- an untreated STI or a pelvic infection

- problems with your womb or cervix

- any unexplained bleeding from your vagina – for example, between periods or after sex

Women who have had an ectopic pregnancy or recent abortion, or who have an artificial heart valve, must consult their GP or clinician before having an IUD fitted.

You should not be fitted with an IUD if there's a chance that you are already pregnant or if you or your partner are at risk of catching STIs. If you or your partner are unsure, go to your GP or a sexual health clinic to be tested.

Using an IUD after giving birth

An IUD can usually be fitted four to six weeks after giving birth (vaginal or caesarean). You'll need to use alternative contraception from three weeks (21 days) after the birth until the IUD is fitted. In some cases, an IUD can be fitted within 48 hours of giving birth. An IUD is safe to use when you're breastfeeding and it won't affect your milk supply.

Using an IUD after a miscarriage or abortion

An IUD can be fitted straight away or within 48 hours after an abortion or miscarriage by an experienced doctor or nurse, as long as you were pregnant for less than 24 weeks. If you were pregnant for more than 24 weeks, you may have to wait a few weeks before having an IUD fitted.

Advantages and disadvantages of the IUD

Although an IUD is an effective method of contraception, there are some things to consider before having one fitted.

Advantages of the IUD

- Most women can use an IUD, including women who have never been pregnant.

- Once an IUD is fitted, it works straight away and lasts for up to 10 years or until it's removed.

- It doesn't interrupt sex.

- It can be used if you're breastfeeding.

- Your normal fertility returns as soon as the IUD is taken out

- It's not affected by other medicines.

There's no evidence that having an IUD fitted will increase the risk of cancer of the cervix, endometrial cancer (cancer of the lining of the womb) or ovarian cancer. Some women experience changes in mood and libido, but these changes are very small. There is no evidence that the IUD affects weight.

Disadvantages of the IUD

- Your periods may become heavier, longer or more painful, though this may improve after a few months.

- An IUD doesn't protect against STIs, so you may have to use condoms as well. If you get an STI while you have an IUD, it could lead to a pelvic infection if not treated.

- The most common reasons that women stop using an IUD are vaginal bleeding and pain.

Risks of the IUD

Complications after having an IUD fitted are rare. Most will appear within the first year after fitting.

Damage to the womb

In fewer than one in 1,000 cases, an IUD can perforate (make a hole in) the womb or neck of the womb (cervix) when it's put in. This can cause pain in the lower abdomen, but doesn't usually cause any other symptoms. If the doctor or nurse fitting your IUD is experienced, the risk of this is very low.

If perforation occurs, you may need surgery to remove the IUD. Contact your GP straight away if you feel a lot of pain after having an IUD fitted as perforations should be treated immediately.

Pelvic infections

Pelvic infections can occur in the first 20 days after the IUD is fitted. The risk of infection is very small. Fewer than one in 100 women who are at low risk of STIs will get a pelvic infection.

Rejection

Occasionally, the IUD is rejected (expelled) by the womb or can move (this is called displacement). This is more likely to happen soon after it has been fitted, although this is uncommon. Your doctor or nurse will teach you how to check that your IUD is in place.

Ectopic pregnancy

If the IUD fails and you become pregnant, your IUD should be removed as soon as possible if you're going to continue with the pregnancy. There's a small increased risk of ectopic pregnancy if a woman becomes pregnant while using an IUD.

Where to get an IUD

Most types of contraception are available free in the UK. Contraception is free to all women and men through the NHS. Places where you can get contraception include:

- most GP surgeries – talk to your GP or practice nurse

- community contraception clinics

- some genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics

- sexual health clinics – these offer contraceptive and STI testing services

- some young people’s services (call the sexual health line on 0300 123 7123 for details)

Find your nearest sexual health clinic by searching your postcode or town.

If you're under 16 and want contraception, the doctor, nurse or pharmacists won't tell your parents or carer, as long as they believe you fully understand the information you're given, and your decisions.

Doctors and nurses work under strict guidelines when dealing with people under 16. They'll encourage you to consider telling your parents, but they won't make you. The only time that a professional might want to tell someone else is if they believe you're at risk of harm, such as abuse. The risk would need to be serious, and they would usually discuss this with you first.

Source: NHS Choices, UK

back-to-top

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) fact sheet

- What is a sexually transmitted infection (STI)?

- How many people have STIs and who is infected?

- How do you get an STI?

- Can STIs cause health problems?

- What are the symptoms of STIs?

- How do you get tested for STIs?

- Who needs to get tested for STIs?

- How are STIs treated?

- What can I do to keep from getting an STI?

- How do STIs affect pregnant women and their babies?

- What can pregnant women do to prevent problems from STIs?

- Do STIs affect breastfeeding?

- Is there any research being done on STIs?

- For more information

- More information on sexually transmitted infections (STI)

What is a sexually transmitted infection (STI)?

It is an infection passed from person to person through intimate sexual contact. STIs are also called sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs.

How many people have STIs and who is infected?

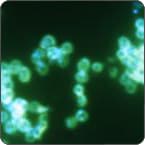

In the United States about 19 million new infections are thought to occur each year. These infections affect men and women of all backgrounds and economic levels. But almost half of new infections are among young people ages 15 to 24. Women are also severely affected by STIs. They have more frequent and more serious health problems from STIs than men. African-American women have especially high rates of infection.

How do you get an STI?

You can get an STI by having intimate sexual contact with someone who already has the infection. You can’t tell if a person is infected because many STIs have no symptoms. But STIs can still be passed from person to person even if there are no symptoms. STIs are spread during vaginal, anal, or oral sex or during genital touching. So it’s possible to get some STIs without having intercourse. Not all STIs are spread the same way.

Can STIs cause health problems?

Yes. Each STI causes different health problems. But overall, untreated STIs can cause cancer, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, pregnancy problems, widespread infection to other parts of the body, organ damage, and even death.

Having an STI also can put you at greater risk of getting HIV. For one, not stopping risky sexual behavior can lead to infection with other STIs, including HIV. Also, infection with some STIs makes it easier for you to get HIV if you are exposed.

What are the symptoms of STIs?

Many STIs have only mild or no symptoms at all. When symptoms do develop, they often are mistaken for something else, such as urinary tract infection or yeast infection. This is why screening for STIs is so important. The STIs listed here are among the most common or harmful to women.

Symptoms of sexually transmitted infections

| STI |

Symptoms |

| Bacterial vaginosis (BV) |

Most women have no symptoms. Women with symptoms may have:

- Vaginal itching

- Pain when urinating

- Discharge with a fishy odor

|

| Chlamydia |

Most women have no symptoms. Women with symptoms may have:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge

- Burning when urinating

- Bleeding between periods

Infections that are not treated, even if there are no symptoms, can lead to:

- Lower abdominal pain

- Low back pain

- Nausea

- Fever

- Pain during sex

|

| Genital herpes |

Some people may have no symptoms. During an “outbreak,” the symptoms are clear:

- Small red bumps, blisters, or open sores where the virus entered the body, such as on the penis, vagina, or mouth

- Vaginal discharge

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Pain when urinating

- Itching, burning, or swollen glands in genital area

- Pain in legs, buttocks, or genital area

Symptoms may go away and then come back. Sores heal after 2 to 4 weeks.

|

| Gonorrhea |

Symptoms are often mild, but most women have no symptoms. If symptoms are present, they most often appear within 10 days of becoming infected. Symptoms are:

- Pain or burning when urinating

- Yellowish and sometimes bloody vaginal discharge

- Bleeding between periods

- Pain during sex

- Heavy bleeding during periods

Infection that occurs in the throat, eye, or anus also might have symptoms in these parts of the body.

|

| Hepatitis B |

Some women have no symptoms. Women with symptoms may have:

- Low-grade fever

- Headache and muscle aches

- Tiredness

- Loss of appetite

- Upset stomach or vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Dark-colored urine and pale bowel movements

- Stomach pain

- Skin and whites of eyes turning yellow

|

| HIV/AIDS |

Some women may have no symptoms for 10 years or more. About half of people with HIV get flu-like symptoms about 3 to 6 weeks after becoming infected. Symptoms people can have for months or even years before the onset of AIDS include:

- Fevers and night sweats

- Feeling very tired

- Quick weight loss

- Headache

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Diarrhea, vomiting, and upset stomach

- Mouth, genital, or anal sores

- Dry cough

- Rash or flaky skin

- Short-term memory loss

Women also might have these signs of HIV:

- Vaginal yeast infections and other vaginal infections, including STIs

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) that does not get better with treatment

- Menstrual cycle changes

|

| Human papillomavirus (HPV) |

Some women have no symptoms. Women with symptoms may have:

- Visible warts in the genital area, including the thighs. Warts can be raised or flat, alone or in groups, small or large, and sometimes they are cauliflower-shaped.

- Growths on the cervix and vagina that are often invisible.

|

Pubic lice

(sometimes called "crabs") |

Symptoms include:

- Itching in the genital area

- Finding lice or lice eggs

|

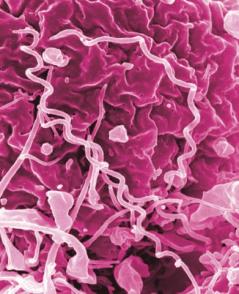

| Syphilis |

Syphilis progresses in stages. Symptoms of the primary stage are:

- A single, painless sore appearing 10 to 90 days after infection. It can appear in the genital area, mouth, or other parts of the body. The sore goes away on its own.

If the infection is not treated, it moves to the secondary stage. This stage starts 3 to 6 weeks after the sore appears. Symptoms of the secondary stage are:

- Skin rash with rough, red or reddish-brown spots on the hands and feet that usually does not itch and clears on its own

- Fever

- Sore throat and swollen glands

- Patchy hair loss

- Headaches and muscle aches

- Weight loss

- Tiredness

In the latent stage, symptoms go away, but can come back. Without treatment, the infection may or may not move to the late stage. In the late stage, symptoms are related to damage to internal organs, such as the brain, nerves, eyes, heart, blood vessels, liver, bones, and joints. Some people may die.

|

Trichomoniasis

(sometimes called "trich") |

Many women do not have symptoms. Symptoms usually appear 5 to 28 days after exposure and can include:

- Yellow, green, or gray vaginal discharge (often foamy) with a strong odor

- Discomfort during sex and when urinating

- Itching or discomfort in the genital area

- Lower abdominal pain (rarely)

|

How do you get tested for STIs?

Tests for reproductive health

Bring our Tests for Reproductive Health (PDF, 306 KB) to your next checkup.

There is no one test for all STIs. Ask your doctor about getting tested for STIs. She or he can tell you what test(s) you might need and how it is done. Testing for STIs is also called STI screening. Testing (or screening) for STIs can involve:

- Pelvic and physical exam — Your doctor can look for signs of infection, such as warts, rashes, discharge.

- Blood sample

- Urine sample

- Fluid or tissue sample — A swab is used to collect a sample that can be looked at under a microscope or sent to a lab for testing.

Sexually transmitted infections testing site

Find an STI testing site near you.

These methods are used for many kinds of tests. So if you have a pelvic exam and Pap test, for example, don’t assume that you have been tested for STIs. Pap testing is mainly used to look for cell changes that could be cancer or precancer. Although a Pap test sample also can be used to perform tests for HPV, doing so isn’t routine. And a Pap test does not test for other STIs. If you want to be tested for STIs, including HPV, you must ask.

You can get tested for STIs at your doctor’s office or a clinic. But not all doctors offer the same tests. So it’s important to discuss your sexual health history to find out what tests you need and where you can go to get tested.

Who needs to get tested for STIs?

Screening tests

- Find out what screening tests you might need

If you are sexually active, talk to your doctor about STI screening. Which tests you might need and how often depend mainly on your sexual history and your partner’s. Talking to your doctor about your sex life might seem too personal to share. But being open and honest is the only way your doctor can help take care of you. Also, don’t assume you don’t need to be tested for STIs if you have sex only with women. Talk to your doctor to find out what tests make sense for you.

How are STIs treated?

The treatment depends on the type of STI. For some STIs, treatment may involve taking medicine or getting a shot. For other STIs that can’t be cured, like herpes, treatment can help to relieve the symptoms.

Only use medicines prescribed or suggested by your doctor. There are products sold over the Internet that falsely claim to prevent or treat STIs, such as herpes, chlamydia, human papillomavirus, and HIV. Some of these drugs claim to work better than the drugs your doctor will give you. But this is not true, and the safety of these products is not known.

What can I do to keep from getting an STI?

You can lower your risk of getting an STI with the following steps. The steps work best when used together. No single strategy can protect you from every single type of STI.

- Don’t have sex. The surest way to keep from getting any STI is to practice abstinence. This means not having vaginal, oral, or anal sex. Keep in mind that some STIs, like genital herpes, can be spread without having intercourse.

- Be faithful. Having a sexual relationship with one partner who has been tested for STIs and is not infected is another way to lower your risk of getting infected. Be faithful to each other. This means you only have sex with each other and no one else.

- Use condoms correctly and every time you have sex. Use condoms for all types of sexual contact, even if intercourse does not take place. Use condoms from the very start to the very end of each sex act, and with every sex partner. A male latex condom offers the best protection. You can use a male polyurethane condom if you or your partner has a latex allergy. For vaginal sex, use a male latex condom or a female condom if your partner won’t wear a condom. For anal sex, use a male latex condom. For oral sex, use a male latex condom. A dental dam might also offer some protection from some STIs.

- Know that some methods of birth control, like birth control pills, shots, implants, or diaphragms, will not protect you from STIs. If you use one of these methods, be sure to also use a condom correctly every time you have sex.

- Talk with your sex partner(s) about STIs and using condoms before having sex. It’s up to you to set the ground rules and to make sure you are protected.

- Don’t assume you’re at low risk for STIs if you have sex only with women. Some common STIs are spread easily by skin-to-skin contact. Also, most women who have sex with women have had sex with men, too. So a woman can get an STI from a male partner and then pass it to a female partner.

- Talk frankly with your doctor and your sex partner(s) about any STIs you or your partner has or has had. Talk about symptoms, such as sores or discharge. Try not to be embarrassed. Your doctor is there to help you with any and all health problems. Also, being open with your doctor and partner will help you protect your health and the health of others.

- Have a yearly pelvic exam. Ask your doctor if you should be tested for STIs and how often you should be retested. Testing for many STIs is simple and often can be done during your checkup. The sooner an STI is found, the easier it is to treat.

- Avoid using drugs or drinking too much alcohol. These activities may lead to risky sexual behavior, such as not wearing a condom.

How do STIs affect pregnant women and their babies?

STIs can cause many of the same health problems in pregnant women as women who are not pregnant. But having an STI also can threaten the pregnancy and unborn baby's health. Having an STI during pregnancy can cause early labor, a woman's water to break early, and infection in the uterus after the birth.

Some STIs can be passed from a pregnant woman to the baby before and during the baby’s birth. Some STIs, like syphilis, cross the placenta and infect the baby while it is in the uterus. Other STIs, like gonorrhea, chlamydia, hepatitis B, and genital herpes, can be passed from the mother to the baby during delivery as the baby passes through the birth canal. HIV can cross the placenta during pregnancy and infect the baby during the birth process.

The harmful effects to babies may include:

- Low birth weight

- Eye infection

- Pneumonia

- Infection in the baby’s blood

- Brain damage

- Lack of coordination in body movements

- Blindness

- Deafness

- Acute hepatitis

- Meningitis

- Chronic liver disease

- Cirrhosis

- Stillbirth

Some of these problems can be prevented if the mother receives routine prenatal care, which includes screening tests for STIs starting early in pregnancy and repeated close to delivery, if needed. Other problems can be treated if the infection is found at birth.

What can pregnant women do to prevent problems from STIs?

Pregnant women should be screened at their first prenatal visit for STIs, including:

- Chlamydia

- Gonorrhea

- Hepatitis B

- HIV

- Syphilis

In addition, some experts recommend that women who have had a premature delivery in the past be screened and treated for bacterial vaginosis (BV) at the first prenatal visit. Even if a woman has been tested for STIs in the past, she should be tested again when she becomes pregnant.